Monday is National Medal of Honor Day. Here are stories of Kansans who received that award

Capt. Riley L. Pitts threw himself on a live grenade to protect his fellow soldiers while fighting in 1967 in Vietnam.

It didn't explode.

Pitts, a 30-year-old married father of two from Wichita, then continued to fight and lead his men until he was killed by enemy fire later that same day as he showed "complete disregard for his personal safety," said the citation for the Medal of Honor he was awarded posthumously in December 1968.

Pitts became the first African-American officer to receive that award, the U.S. military's highest decoration.

The Capital-Journal is highlighting Pitts and these four other Kansans who have received the Medal of Honor over the past 100 years in recognition of Monday's observance of National Medal of Honor Day, first celebrated in 1991 after Congress created it to foster public appreciation and recognition of Medal of Honor recipients.

Rev. Emil J. Kapaun (awarded in 2013)

Capt. Emil J. Kapaun, a Catholic priest, was honored for acts that included pushing aside an enemy soldier who was about to execute a wounded U.S. soldier after Kapaun and that soldier were captured during the Korean War.

Kapaun saved the life of Sgt. 1st Class Herbert A. Miller, who expressed appreciation 62 years later when the Distinguished Service Cross Kapaun received posthumously in 1951 was upgraded in 2013 to the Medal of Honor.

A native of the unincorporated community of Pilsen in Marion County, Kapaun became a priest in 1940, joined the U.S. Army Chaplain Corps in 1944 and served in India toward the end of World War II. He was promoted to captain in 1946, left active duty later that year, returned to active duty in 1948 and was sent in 1950 to Korea.

Kapaun was awarded the Bronze Star Medal with a "V" device for valor after he and an assistant in 1950 braved enemy fire to rescue a wounded soldier who had become stranded during a retreat.

Kapaun's Medal of Honor citation describes the heroism he then showed on Nov. 1 and 2, 1950, as Chinese soldiers attacked the soldiers with whom he served. Kapaun "calmly walked through withering enemy fire in order to provide comfort and medical aid to his comrades and rescue friendly wounded from no-man's land," it said.

Though the Americans repelled the assault, the able-bodied soldiers were ordered to evacuate. Kapaun chose to stay behind with the wounded, realizing that would result in his "certain capture," his Medal of Honor citation said.

"As Chinese Communist Forces approached the American position, Chaplain Kapaun noticed an injured Chinese officer among the wounded and convinced him to negotiate the safe surrender of the American Forces," it said "Shortly after his capture, Chaplain Kapaun, with complete disregard for his personal safety and unwavering resolve, bravely pushed aside an enemy soldier preparing to execute (Miller)."

Kapaun then carried and supported Miller, who had a broken ankle, for several days as their group was marched to a prison camp. Miller lived 73 years more, dying last November at age 97.

As a prisoner, Kapaun boosted morale among fellow prisoners, stole food for men who needed it and smuggled in drugs used to treat the prisoners for dysentery. He died at age 35, of malnutrition and pneumonia, on May 23, 1951.

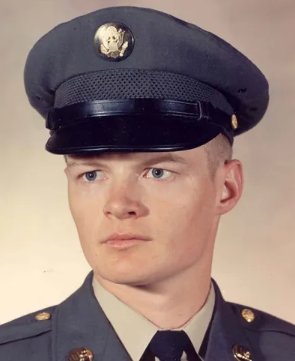

Danny J. Petersen (awarded in 1974)

Danny J. Petersen, 20, held the rank of Specialist 4 and listed his hometown as Horton. He grew up in northeast Kansas, at one point living in Topeka and attending Curtis Junior High School. Petersen entered the Army in March 1969 and was sent that August to Vietnam.

He was posthumously awarded the Medal of Honor in July 1974 for heroism displayed Jan. 9, 1970, as Petersen commanded an armored personnel carrier against North Vietnamese troops who had disabled another U.S. armored personnel carrier and pinned down its crew with heavy weapons fire.

Petersen maneuvered his vehicle into a position between the disabled vehicle and the enemy and fired upon the enemy's well-fortified position, which enabled the crew of the disabled vehicle to repair it, his Medal of Honor citation said.

Under heavy fire, Petersen maneuvered his vehicle to within 10 feet of the enemy. His driver was wounded, and Petersen carried him 45 meters across a bullet-swept field to a secure area, his citation said.

Petersen then voluntarily returned to his vehicle and stood alone providing cover fire against numerous North Vietnamese troops, so his fellow platoon members could withdraw.

His Medal of Honor citation said: "Despite heavy fire from three sides, he remained with his disabled vehicle, alone and completely exposed. Specialist Petersen was standing on top of his vehicle, firing at the enemy, when he was mortally wounded."

Petersen was honored in 1994 when the stretch of US-75 highway between K-9 and K-16 highways in northern Jackson County became the "Danny J. Petersen Memorial Highway."

Riley L. Pitts (awarded in 1968)

A native of Oklahoma, Pitts graduated from Wichita State University and worked for Boeing before serving seven years in the Army, where he attained the rank of captain, said the website of the Kansas Historical Society. He was sent in December 1966 to Vietnam.

Pitts was honored posthumously for heroism displayed Oct. 31, 1967 — one month before he was to be rotated home — while commanding a company that landed by helicopter in an area were Viet Cong soldiers opened fire with automatic weapons.

Pitts led an attack that overran the enemy positions, then was ordered to take his unit to reinforce another company that was fighting a strong enemy force. As company members moved forward, they found themselves under fire from three directions, including four enemy bunkers, two within 15 meters of Pitts, his Medal of Honor citation said.

With dense jungle growth rendering rifle fire ineffective against the bunkers, Pitts picked up a grenade launcher and began pinpointing targets, then seized a grenade that had been taken among from the gear of a captured Viet Cong soldier, it said.

"Capt. Pitts lobbed the grenade at a bunker to his front, but it hit the dense jungle foliage and rebounded," his Medal of Honor citation said. "Without hesitation, Capt. Pitts threw himself on top of the grenade which, fortunately, failed to explode."

Pitts directed the repositioning of his men to allow artillery to be fired upon the area they were attacking, then again led them toward the enemy positions while personally killing at least one more Viet Cong soldier, his citation said.

"The jungle growth still prevented effective fire from being placed on the enemy bunkers," it said. "Capt. Pitts, displaying complete disregard for his life and personal safety, quickly moved to a position which permitted him to place effective fire on the enemy. He maintained a continuous fire, pinpointing the enemy's fortified positions, while at the same time directing and urging his men forward, until he was mortally wounded."

Stanley T. Adams (awarded in 1951)

Seeing that close quarters fighting would be needed to defeat a much larger enemy force, Master Sgt. Stanley T. Adams led 13 men in a successful bayonet charge against them during the Korean War.

Adams was born in DeSoto and was living in Olathe when he joined the Army to fight in World War II. He was wounded in action while fighting in North Africa and Italy. Adams then served in Japan as part of the American occupation force before going in 1950 to fight in Korea.

Adams, then 28, received the Medal of Honor for heroism displayed during the early-morning hours of Feb. 3, 1951.

"Observing approximately 150 hostile troops silhouetted against the skyline advancing against his platoon, M/Sgt. Adams leaped to his feet, urged his men to fix bayonets, and he, with 13 members of his platoon, charged this hostile force with indomitable courage," the Medal of Honor citation said.

Adams was knocked to the ground by a bullet that struck him in the leg as he was within 50 yards of the enemy, it said.

"He jumped to his feet and, ignoring his wound, continued on to close with the enemy when he was knocked down 4 times from the concussion of grenades which had bounced off his body," his citation said. "Shouting orders, he charged the enemy positions and engaged them in hand-to-hand combat where man after man fell before his terrific onslaught with bayonet and rifle butt."

After nearly an hour of combat, Adams and his men routed the enemy, killing more than 50 and forcing the rest to withdraw.

Adams received the Medal of Honor in July 1951. He served in the Army until 1970, retiring as a lieutenant colonel. Adams died at age 76 in 1999. His wife, Jean Adams, donated his Medal of Honor to an Oregon veterans' home.

Donald K. Ross (awarded in 1942)

Kansas native Donald K. Ross was honored for heroism shown during the Dec. 7, 1941, Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. He became the first World War II recipient of the Medal of Honor.

A native of Beverly in Lincoln County, Ross joined the Navy in 1929. He was serving as a warrant officer machinist on the battleship USS Nevada when it was badly damaged by bombs and torpedoes during the Pearl Harbor attack.

Amid extreme smoke, steam and heat in the ship's forward dynamo room, Ross "forced his men to leave that station and performed all the duties himself until blinded and unconscious," his Medal of Honor citation said.

"Upon being rescued and resuscitated," Ross returned and secured the forward dynamo room, then proceeded to a separate dynamo room, "where he was later again rendered unconscious by exhaustion," it said.

"Again recovering consciousness, he returned to his station where he remained until directed to abandon it," the citation said.

Ross' actions kept the battleship under power until it was beached, preventing it from sinking in a channel and blocking other ships from using the harbor. He was awarded the Medal of Honor in April 1942.

Ross served the rest of World War II on the Nevada and was promoted to captain from commander at the time of his retirement from the Navy in 1956. He then had the honor of introducing President George H.W. Bush in 1991 during 50th anniversary ceremonies at Pearl Harbor.

Ross died at age 81 in 1992. He and his wife, Helen Ross, had four children.

What other Kansans have been honored since World War II?

The website of the Kansas Historical Society identifies the following other Kansans as having received the Medal of Honor over the past 100 years:

• William L. McGonagle, for heroism shown when the U.S. Navy ship he captained was attacked by Israeli forces during the 1967 Israeli-Arab War.

• Jack Weinstein, for heroism shown during the Korean War.

• Harold W. Bauer, Richard Cowan, Walter D. Ehlers, William D. Hawkins, Thomas E. McCall and Grant F. Timmerman, for heroism shown during World War II.

Contact Tim Hrenchir at threnchir@gannett.com or 785-213-5934.

This article originally appeared on Topeka Capital-Journal: Medal of Honor Day: Here are the stories of five Kansas recipients