Mom got caught in the polio epidemic's last gasp, but she prevailed. So will we.

In 1954, when I was 4, we lived in Dallas. On hot summer nights, all five of us — Mom, Dad, my two little brothers and I — slept in the living room because it had an air conditioner. Outside in the morning, it was usually in the upper 80s already, so instantly we were hot as winter oatmeal and sticky as flypaper.

But hey, we had an air conditioner, a wading pool and a 10-by-10-foot patio. Life was good.

Then in August, Mom disappeared.

Mom had been tired — more like exhausted. Every day, she had chased us three kids, ages 4, 3 and 2. No matter what, she kept us clean, tidy and busy. That August, she was going with Dad to the Texas Daily Newspaper Association conference, so she shopped downtown for a new outfit.

When the parking attendant returned Mom’s car that afternoon, she thought the clutch didn’t work. She wondered what the attendant had done. But the problem was Mom’s left leg didn’t work. She managed to drive home, but later, ferocious muscle spasms took over.

Virginia fails: My parents caught COVID while vaccines languish unused

Our family physician suspected polio, urging Dad to get Mom to the Dallas County hospital that took acute cases. Dad carried Mom toward their 1949 Chevrolet.

“Put me down,” Mom insisted. “I can walk.” But she couldn’t.

At the hospital, nurses instantly parked Mom in isolation. Dad could see her only through a small glass square in the door. No intercom; indeed, Mom was too sick to use such a thing.

The virus boiled through Mom's body

Kathleen Baugh Gleason, my mom, was part of an epidemic. In 1952, there were 58,000 cases of polio in the United States. The following year, there were 35,000.

Typically, polio outbreaks caused more than 15,000 cases of paralysis each year. The word “polio” terrified everybody.

When Mom got sick, she was 27 years old — and a looker. She had ivory skin, copper-penny hair, a slender build and keen appreciation for I. Miller shoes, both stylish and expensive. My dad, Bob Gleason, loved her, and they were happy parents.

That 1954, the United States undertook a field trial unprecedented in scope: 1.8 million children received a placebo or the polio vaccine developed by virologist Jonas Salk and his team.

Meantime, the polio virus boiled through Mom’s body: Nobody knew whether she would live or die. Dad shuttled among home, hospital and his job directing The Southwest School of Printing, which graduated linotype operators.

At home, I had a turquoise party dress: round collar, English smocking, perky sash that tied in back. After I grew up, Dad told me that while Mom was sick, I cut up the dress. I remember the dress but not the cutting up.

Mom and Dad had medical insurance on him but not her. Money had been very tight. They had their house but little else.

One day, Dad dropped by to see Edward Musgrove “Ted” Dealey, publisher of the Dallas Morning News. They talked presses and printing, but Dealey also asked about Mom. He realized Dad needed help so connected him with the March of Dimes.

Care and casseroles

In 1938, Franklin D. Roosevelt had led the effort to start the National Foundation for Infantile Paralysis. It led to the first March of Dimes campaign that year. Americans were encouraged to send dimes or whatever they could to fund research. The money rolled in.

At the Dallas office, a social worker got us a housekeeper. Dad made breakfast each morning, then Becky took over until he came back at dinner.

Dad lied about paying Becky. He said $30 a week, but Mom knew it had to be more. Actually, the March of Dimes paid for Becky — and eventually Mom’s hospital bill, all six months of it.

We kids and Dad weren’t sick, but the health department slapped a sign on our front door: “Contagion: Do Not Enter.” We had an aunt and uncle in Dallas, but they had their hands full with their kids so didn’t come around. Nevertheless, friends Monica Moran and Faye Butsch, women who had families of their own, not only brought casseroles straight into the house but for weeks on end.

Doctor: My vaccine was like a flu shot. I got one and went right back to work.

Meantime at the hospital, Mom got sicker. A priest gave her the last rites of the Catholic Church, but ever the optimist, Mom thought she was getting Holy Communion.

Then, about two weeks into the siege, the virus stopped short of Mom’s lungs. Doctors didn’t know why, but it became clear Mom was going to live. She told Dad, “I will get better. Don’t you let anything happen to our children.”

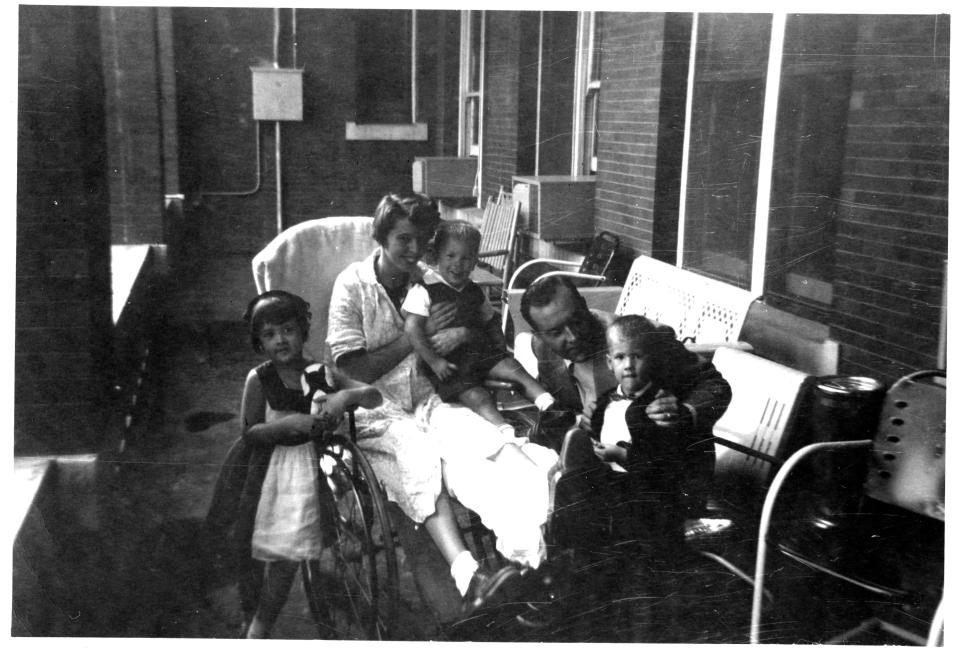

On Sundays, Dad gussied us in our best clothes and took us to see Mom. By that time, she got around in a big, wooden wheelchair, a thing about the size of a Humvee, with her left leg stretched out on a wooden panel.

Grammie Baugh also visited from Cleveland. The day she was to arrive, Mom waited in her wheelchair next to the hospital elevator, eager to show her mother that she had not only survived but was getting well. When Gram emerged, her face fell — and Mom’s spirit sank to the basement. Within hours, though, Mom had scraped herself back together, ready to move on.

Life something like normal

Some months after that — April 12, 1955 — Jonas Salk and his team announced the polio vaccine trials a huge success. The nation celebrated as if it were the end of a war — and in a way, it was.

That day, journalist Edward R. Murrow asked Salk who owns the patent for the vaccine. “Well, the people, I would say," he replied. "There is no patent. Could you patent the sun?”

Today, polio is all but eradicated worldwide.

Deaths of despair: Like Tommy Raskin, I concealed my pain. Suicide prevention requires professional help.

That April 12 was the 10th anniversary of FDR’s death. It was also Dad’s 31st birthday; he and Mom celebrated both his birthday and her being home. She got around on wooden crutches.

Several times a week, Mom exercised at a motel pool near our house. My job was to watch my brothers at the shallow end while Mom exercised at the deep end. We kids regarded the pool a great outing; lunch was often egg salad sandwiches and lemonade that Mom packed in a cooler.

She couldn’t stand at the kitchen counter so worked at a card table. She used a kitchen chair with a yellow vinyl seat; guys at the Southwest School of Printing had added steel coasters.

One day, while we kids were with a babysitter, Mom went shopping for Oxford shoes. “I hated that,” she said. “I realized I wouldn’t be wearing high heels. I cried. But then I realized I was lucky to be alive.”

Another day, Mom went to confession at church. She couldn’t kneel so instead stood in the confessional. When the priest slid open the screen, Mom said, “Bless me, Father, for I have sinned.” The priest craned his neck upward, and Mom nearly guffawed. “I should have said, ‘Bless me, Father, for I am a giant.’ ”

I think William Faulkner was right in his Nobel speech when he said humans will not merely endure; they will prevail. There’s a lot to be said for courage. And yellow vinyl kitchen chairs.

Cathy O’Donnell is a retired news reporter who lives in Seattle.

You can read diverse opinions from our Board of Contributors and other writers on the Opinion front page, on Twitter @usatodayopinion and in our daily Opinion newsletter. To respond to a column, submit a comment to letters@usatoday.com.

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: The polio epidemic's last gasp: Mom survived with gumption and grace