The miracle on Skull Creek: When the bridge to Hilton Head was hit by a barge

It was nothing like the sudden collapse of the Francis Scott Key Bridge when a gigantic freighter crashed into it last week in Baltimore, tragically killing six.

But when a barge plowed into the swing-span bridge connecting Hilton Head Island to the mainland in the dead of a raw and rainy night exactly 50 years ago, the result for 10,000 islanders left with no road was devastating.

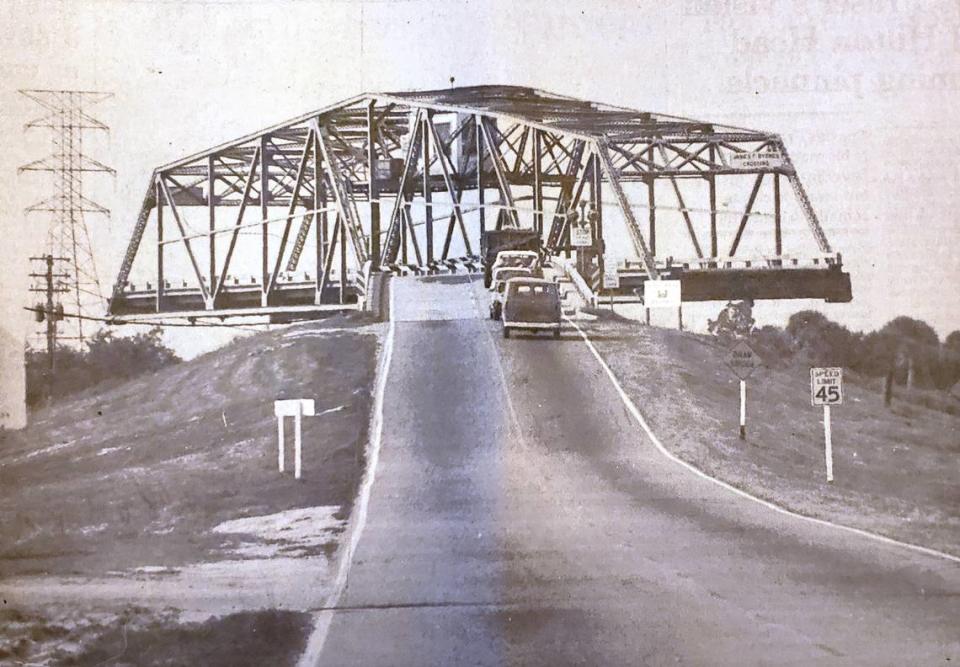

The barge being pushed up the Atlantic Intracoastal Waterway by a tugboat dislodged and shifted a cement bridge piling, moving it three feet.

The bridge couldn’t close.

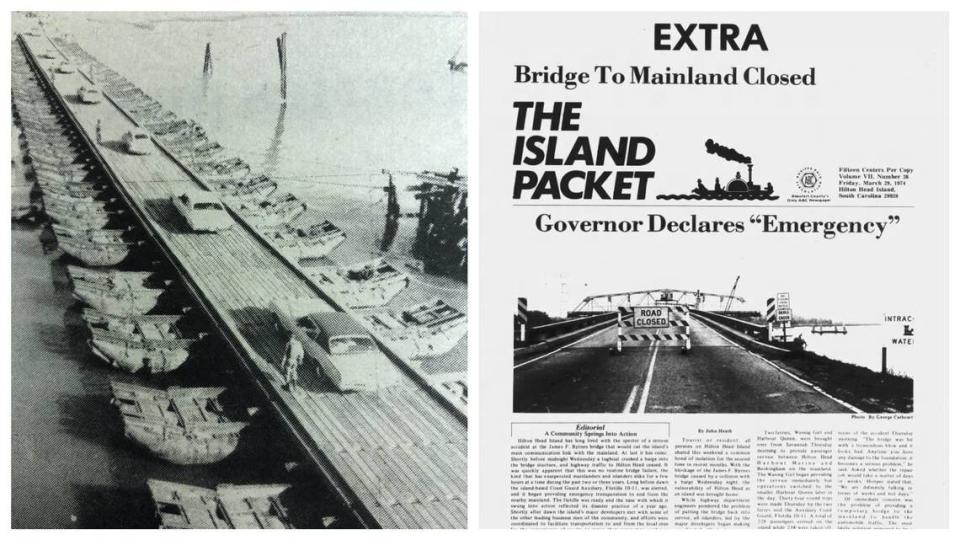

The Island Packet, then a tabloid published two days a week, came out with the only “EXTRA!” it would publish until the afternoon of 9/11.

Editor Ralph Hilton told how the biggest story in decades began, as seen by banker James Rowe. He was one of the first motorists to get stopped when the bridge swung open for the passing barge.

“He sat in the car watching the barge lights loom up against the bridge — and then he didn’t see them pass through on the Savannah side.

“After a while he stepped out into the rain and walked forward. There was a lot of shouting going on. Mr. Rowe remembers some of it very well.

“ ‘Did we hit the bridge?’ ” came a megaphoned voice from the tugboat.

“There followed a megaphoned shout from the bridge tender, high up in the superstructure of the bridge. It was a profane affirmative.

“From the tugboat: ‘If I leave my name and number can I go on through?’

“From the bridge: ‘Hell, no!’ ”

Hell broke loose

It slowly became obvious the bridge would be out not from hours or days but for weeks.

It turned out to be four weeks — weeks of heroism, confusion, sacrifice, military might and one incredible engineering feat that will forever live in infamy for Hilton Head.

The fretful episode showed the vulnerability of the supposedly idyllic life on an island that was on the cusp of a growth explosion in a county that was still largely rural.

It engaged a citizen army. It was aided by cooperation on local, county, state and federal levels.

It showed a community with lax emergency planning.

And it showed an island in desperate need of incorporation. Indeed, the man appointed leader of a hastily-recruited citizen Emergency Council would become the island’s first mayor a decade later.

But just shy of midnight on Wednesday, March 27, 1974, the big picture didn’t really matter. Food, gasoline, medical emergencies, jobs, paychecks, services, stranded tourists and, of course, the liquor supply were the biggest worries.

Instant crisis

One of the first to hear the news was Paul Holmes, captain of the volunteer Hilton Head Rescue Squad, by a radio transmission for a Beaufort County Sheriff’s Office deputy at the bridge. He enacted the squad’s emergency plan, moving ambulances around and engaging a helicopter from Marine Corps Air Station Beaufort for any medical emergencies.

Col. Louis Smunk, the county’s director of Civil Defense, responded with his assistants.

And Holmes called the de facto island leadership of the era: the major developers, sometimes called the “benevolent dictators.”

Retired Lt. Gen. Howard E. “Doc” Kreidler, vice commander of the Coast Guard Auxiliary Flotilla 10-11, was awakened, and he called operations officer Alex Turner. By 2 a.m. more than 20 “mates” had assembled and began to fan out to area docks in their personal pleasure craft, providing the first transportation to and from the island.

Legendary island character, commercial fisherman and restaurateur Benny Hudson, on his own initiative, called a friend in Savannah who owned large river sight-seeing boats and persuaded him to establish a ferry route between Buckingham Landing on the mainland and Hilton Head Harbor.

The Waving Girl, Miss Charleston and the Harbor Queen quickly began transporting thousands of people.

Parking was set up on the mainland in the pecan grove at Moss Creek. The developers arranged buses, limousines and private cars to transport people to and from the dock on the island.

“Chaos prevailed throughout the day Thursday and Friday, but some constructive actions were taken nevertheless,” the Packet reported.

Twisting arms

Brig. Gen. Fred C. Craft, director of the S.C. Emergency Preparedness Agency, flew in.

In conjunction with Smunk, state Sen. James M. Waddell Jr. of Beaufort, and retired Army Lt. Gen. Albert O. Connor, president of the island’s Community Association, Gov. John West was asked to declare a state of emergency, which he did.

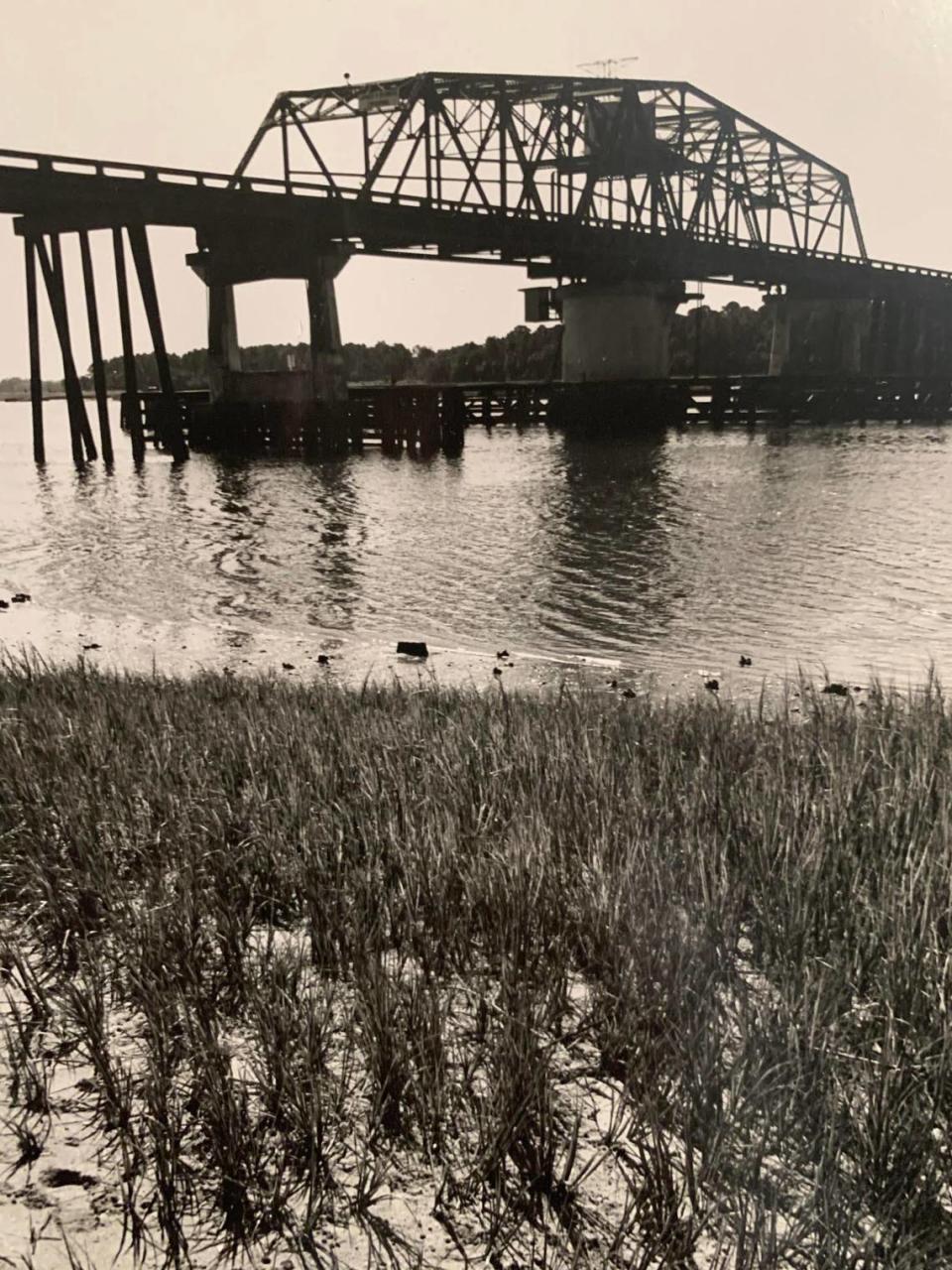

With this new access to federal help, they decided to the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers should install a pontoon bridge across Skull Creek beside the disabled bridge.

Joab Dowling, a Beaufort attorney who did a lot of practice on Hilton Head, interrupted a flight to Atlanta to use his position as civilian aide to the Secretary of War to ask the Pentagon to hop-to. He also enlisted U.S. Sen. Strom Thurmond, but the Army “gave a somewhat less than enthusiastic response” to moving that much equipment and manpower from Fort Bragg and elsewhere, the Packet reported.

Connor, the head of the Community Association, was only two years out of active service as commanding officer of the 3rd Infantry Division in Germany. He was credited with helping get permission from Disney Productions to use Walt Disney’s Rocky the Bulldog cartoon character by the “dogface soliders” of the 3rd ID. But on this day, he was compelled to “try to do some arm-twisting on my own” to impress a buddy in the service just how desperate the situation was on Hilton Head.

Within 12 hours, the 36th Engineer Group from Fort Bragg, under the command of Col. Newman A. Howard Jr., was on the move.

Five hundred officers and men and 200 trucks loaded with equipment arrived on Saturday from Fort Bragg and Fort Belvoir, Virginia. They began working around the clock on Sunday morning.

Citizens and soldiers

The U.S. Navy also responded with two large landing craft to haul heavy freight, food and gasoline to the island.

The Beaufort-Jasper Comprehensive Health Services did the same with its old military landing craft skippered by islander David Jones II.

The National Guard sent troops to work with state police in managing people and traffic at Buckingham Landing on the mainland.

Citizens were also on the move — sometimes literally. Shrimp boats became ferries, and shrimp docks became lifelines as an estimated 5,000 people per day were hauled to and from the island.

And hundreds of workers walked across the disabled bridge daily after a diver confirmed that it was not subject to “sudden collapse.”

But supplies were getting short.

Construction on the island nearly stopped.

Schools were closed.

And the response by community leaders was somewhat organized, but no one was in charge.

That’s when they tapped retired CIA officer and community activist Ben Racusin to organize and lead an “Emergency Council” to coordinate local activities with government agencies.

Racusin put an individual in charge of fuel, food, resort activity, motor transport, water transportation, medical and fire emergency, security (headed by retired U.S. Army Col. Ben Vandervoort whose heroics on D-Day were portrayed by John Wayne in the movie “The Longest Day”), building construction, commercial supplies and movement of workers.

It was described as hectic and stressful as a busy day at the New York Stock Exchange, but slowly the “crisis” became a mere “problem.”

Corps of Engineers miracle

The bridge reopened for good on April 22, and no other catastrophe struck it until it was replaced by today’s fixed-span bridge in 1983.

The Coast Guard concluded that the blame could not be placed on licensed personnel, equipment or the weather.

It said the primary cause “… was an adverse flood tidal current that apparently sets in a southeastern direction in the area of the starboard opening …”

It was determined that the bridge pilings needed better protection.

Locally, Retired Army Maj. Gen. Charles E. Johnson reported to the island Public Service Council that island emergency procedures needed to be “better defined.”

Connor of the Community Association asked retired Army Maj. Gen. Walter M. Higgins Jr., who led the lead battalion of the 2nd Infantry Division’s at Omaha Beach in Normandy, to devise an emergency plan for the island.

Slowly, those things would happen as evidenced by the contrast in the emergency response and clean-up after Hurricane Matthew blasted the island in 2016.

In the great bridge crisis of 1974, the game-changer was the pontoon bridge, an achievement in the swirling tides that was later seen as miraculous.

The officer in charge recalled it with tears in his eyes when he was the keynote speaker at the dedication of the 20th Engineer Brigade Memorial Stone at Fort Bragg in 2016.

Then 86, retired Col. Newman Howard Jr. recalled the origins of the brigade just two months after the Hilton Head heroics.

The Fayetteville Observer reported what he said about the feat: On the Sunday morning when construction began, the Corps of Engineers told the governor that if everything went fine, it should have a bridge open in three weeks.

But there was local protest, and here’s how the colonel responded:

“ ‘I said all things being equal, I think we can have it open by Wednesday,’ he recalled to a ripple of laughs. Soon after, Howard received a phone call from an engineer general telling him how stupid he was.

“ ‘You know when that bridge opened?’ he then asked the crowd.

“ ‘When’s that?’

“ ‘Wednesday morning. That’s what being in the military is all about. ... ‘ ”

“The elderly commander’s face then began to slightly quiver.

“ ‘You know what? Those kids, those officers, those noncommissioned officers and those soldiers — they did it,’ he said. ‘I didn’t do anything but watch them. I don’t take any credit for it.’ ”

David Lauderdale may be reached at LauderdaleColumn@gmail.com.