‘Miracle’ herpes treatment eradicates tumours in terminally-ill cancer patients

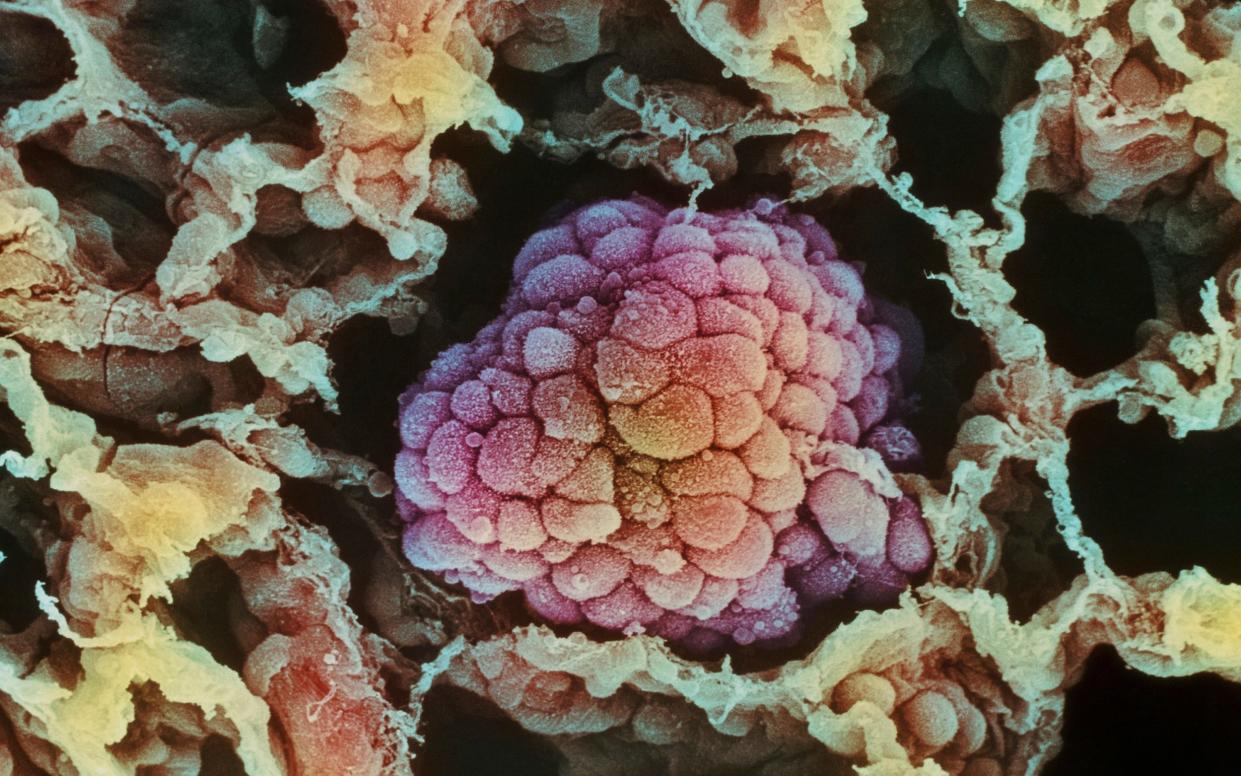

Terminally-ill cancer patients have seen their tumours completely eradicated or shrunk after being treated with a genetically-engineered version of the herpes virus.

Scientists at the Institute for Cancer Research in London have developed a new therapy which infects and destroys cancer cells while also rallying the immune system.

In early trials to assess the safety of the therapy, one quarter of patients with end-of-life cancer saw their tumours stop growing, shrink or disappear completely.

Krzysztof Wojkowski, 39, a builder from West London who had no treatment options left after developing a salivary gland tumour, has been cancer-free for two years since taking part in the trial at the Royal Marsden in London in 2020.

“I was told there were no options left for me and I was receiving end of life care,” he said.

“I had injections every two weeks for five weeks which completely eradicated my cancer.

“I’ve been cancer-free for two years now, it’s a true miracle, there is no other word to describe it. I’ve been able to work as a builder again and spend time with my family, there’s nothing I can’t do.”

Virus causes cancer cells to burst

The genetically engineered virus - called RP2 - is injected directly into the tumour where it multiplies, causing cancer cells to burst from within.

It also blocks a protein called CTLA-4 which dials down the immune system, and so gives the body more of a chance to fight off the cancer. In addition, the virus also produces molecules which spark the immune system into action against cancer.

The therapy was tested on 39 patients with cancers including skin, oesophageal and head and neck cancer who had exhausted all other treatments.

Results showed that around one quarter saw a benefit.

The herpes simplex virus is a common infection, which many people already carry latently without problems.

Researchers looked at patient biopsies before and after RP2 injections and found positive changes in the tumour’s “immune microenvironment” – the area immediately around the tumour. Injections led to more immune cells in the area, including CD8+ T-cells, and “switched on” genes linked to the “anti-cancer” immune response.

The team found that most side effects of RP2 were mild – some of the most common were fever, chills, and fatigue. None of the side effects were serious enough to require medical intervention.

Professor Kristian Helin, chief executive of The Institute of Cancer Research, London, said: “Viruses are one of humanity’s oldest enemies, as we have all seen over the pandemic. But our new research suggests we can exploit some of the features that make them challenging adversaries to infect and kill cancer cells.

“It’s a small study but the initial findings are promising. I very much hope that as this research expands we see patients continue to benefit.”

Potential to become new treatment option

Study leader Kevin Harrington, professor of biological cancer therapies at The Institute of Cancer Research, said: “Our study shows that a genetically engineered, cancer-killing virus can deliver a one-two punch against tumours – directly destroying cancer cells from within while also calling in the immune system against them.

“It is rare to see such good response rates in early-stage clinical trials, as their primary aim is to test treatment safety and they involve patients with very advanced cancers for whom current treatments have stopped working.

“Our initial trial findings suggest that a genetically engineered form of the herpes virus could potentially become a new treatment option for some patients with advanced cancers – including those who haven’t responded to other forms of immunotherapy.

“I am keen to see if we continue to see benefits as we treat increased numbers of patients.”

The research was presented at the 2022 European Society for Medical Oncology Congress (ESMO), and the team are hoping to move to bigger trials.