Opinion: ‘Minor’ Errors In Medical Records Can Have Major Consequences

“Quality” is a buzzword in many industries ― but in health care, it’s lumped in with “safety,” since poor quality can lead to much more than just customer dissatisfaction.

Medical errors are the third leading cause of death in the U.S., according to Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine researchers: Each year, approximately 250,000 patients in the U.S. die due to such errors. But more often than not, medical errors hurt patients in unobvious ways, just as an illness doesn’t always present itself clearly and instead takes root perniciously, over time and under the radar. They’re a sign of a much more severe ailment that plagues our entire health care system.

One place these errors lurk is in documentation and medical records.

As long as people have been practicing medicine, they’ve been keeping records ― if only for the purpose of billing and not necessarily to facilitate continued and coordinated care. Today, medical documentation, whether paper or electronic, serves a number of purposes, facilitating billing and patient care and serving as evidence to help doctors avoid lawsuits (or help patients litigate).

Though we’ve seen a major push in the last decade to digitize health information and make it more widely accessible to both providers and patients, dreams of the “shared electronic medical record” have been slow to come to fruition.

Why? Because providers and health care systems are being asked to switch to new technology, which requires an investment of finances and time. And if health care providers in this country are short on anything, it’s time.

Recordkeeping isn’t quite as simple as people may think. I once worked in a hospital basement as a medical records clerk. It was a good job, and though I didn’t know it at the time, it gave me an incredible amount of insight into the inner workings of America’s health care system (an insight I’ve relied on many times since as a person with chronic illness).

As a records clerk, I frequently took calls from medical transcriptionists. In some offices, dictation is automated into reports through voice recognition software, but this is an imperfect practice and often requires additional double-checking by a real human.

Something that seems like a minor error — a misspelling, for example — can have consequences if that record is ever pulled as part of a malpractice suit. It can also mislead a future provider, influence how the office’s service is coded and therefore billed, or even confuse or mislead the patient when he or she is reviewing records.

Doctors are human too, and they often dictate late at night after long shifts. Mistakes they didn’t make during a surgery can occur in the retelling of it.

It wasn’t uncommon to come across an operative note in which a doctor dictated that they’d operated on the patient’s left leg, only to later say it was the right. A medical transcriptionist would usually catch this type of error, notify us in the medical records office, and we’d then place a call to the doctor to confirm which leg they meant.

Sometimes, though, these errors made it into a patient’s official record, and it wasn’t always because someone just didn’t notice. Staff didn’t always have the proper privileges to make a correction, and if they even viewed a patient record, let alone made alterations to it, they could face disciplinary action.

Ideally, computer systems would be able to automate these processes effectively and take humans out of the equation, giving doctors more time with patients. But in my experience, the less that humans were involved in the oversight and the more heavily the records relied solely on technology (even with stop-gap measures and programming meant to sound alarms when information didn’t compute), the more often aberrations found their way into records ― if not permanently, then at least long enough to conceivably do some damage.

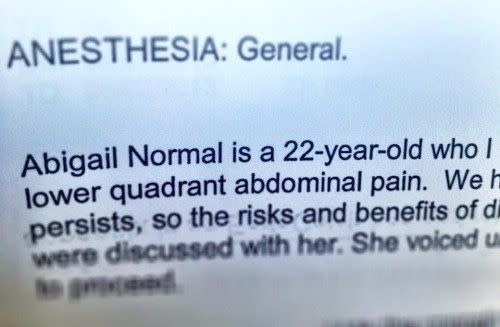

Errors were often harmless and more amusing than anything else for us clerks. I say this as someone who has an op note in my personal medical records in which my name is written “ABIGAIL NORMAL” — the formal version of the inescapable Mel Brooks “Young Frankenstein” Abby Normal references that have followed me my entire life.

Errors can also be more nefarious. I was recently reviewing my own chart with a nurse before a routine appointment, only to be informed that at some point since I’d last reviewed my records, my chart had been altered to say I had eight sisters, all of whom were in good health. I don’t have any sisters.

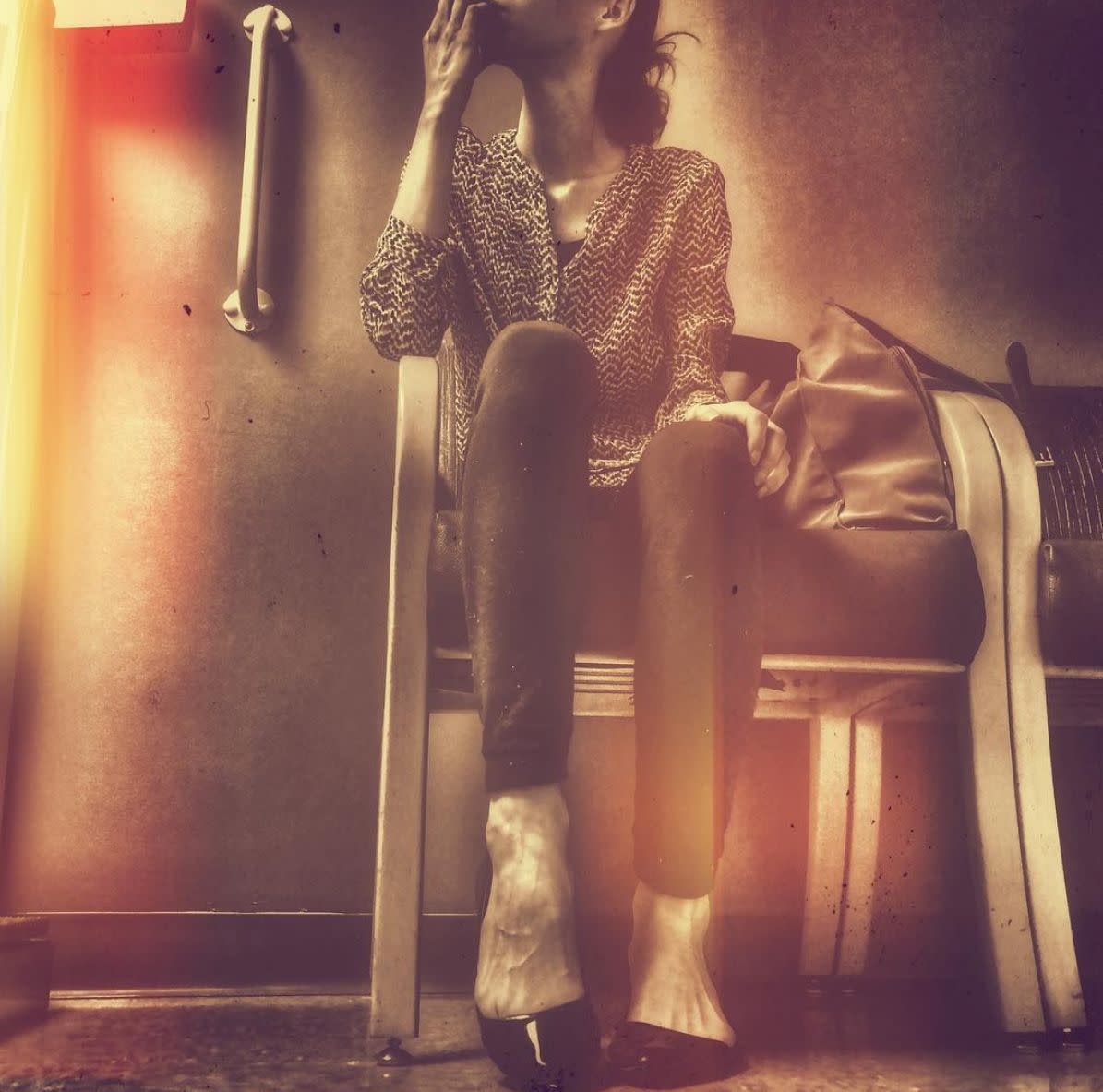

Then, as the nurse reviewed my ever-growing list of health issues, she paused and looked at me for a moment. I’ve lost an extreme amount of weight over the last year as the result of chronic illnesses and I look distressingly frail, so I’m used to this. But then, the nurse read from her computer with a slight wince: “Anorexia. Are you doing better now?”

I stared at her agape before spitting a confused and considerably miffed “What?!” in her general direction. I do not have anorexia nervosa, but if I did, in what universe would it have been OK for someone to assign a diagnosis to me without telling me first?

When I told my doctor about the error during our appointment, she determined that my chart should have said “anorexic” ― the medical term for loss of appetite. Anorexia nervosa would have been a diagnosis in and of itself — a complex mental illness, in fact.

This error was easily corrected, but that doesn’t mean it was minor. When I bemoaned the experience on Twitter afterward, many responded with similar stories of their own.

Love HuffPost? Become a founding member of HuffPost Plus today.

This might have been in my insurance records, but my age got coded wrong so I started getting frantic calls from my insurance company to manage my "high risk" pregnancy because they thought I was 80 years old. I told them that would be a medical miracle (I was 35 at the time)

— Ruth Laura Edlund (@tdgor) June 1, 2018

So far this year I have been a totally other person, and somehow got nonexistent diabetes that I only found out about when my insurer wanted to “help me manage” it.

— Gemma Kennedy (@gnoellekennedy) May 31, 2018

Things that are completely incompatible with other diagnosis. One of my neurologists had a major WTF moment as she took off Sjogren's and CMT diagnoses from my chart since I... don't have them. I have some symptoms, but they're from my main condition. Sigh.

— Natalie (@_Nataliea) May 31, 2018

Today, health care systems and providers must abide by a number of regulations that protect a patient’s privacy if they want to get paid, but we have a long way to go in assessing ― and addressing — the safety and efficacy of electronic medical records. Reports over the last several years suggest that medical professionals are aware of problems with electronic records and that they’ve become common.

Still, there’s still no solid research, no hard numbers, to prove how often or to what degree these errors directly harm patients. One 2017 study from the Patient Safety Authority in Pennsylvania reported that 70 percent of medication errors in included patients’ charts actually reached those patients. Three of those errors involved medications like insulin, opioids and anticoagulants — all of which have the potential to kill a patient if they’re administered incorrectly.

Ideally, patients can learn of these errors while they’re reviewing the information in their charts at the beginning of their appointments ― not when they’re in the midst of an emergency.

The more concerning scenario is when an error is present but the patient is not, thus making its way into the patient’s care when they’re unable to speak up.

The electronic medical record endgame of “one patient, one record” is still worth pursuing; from cost to care coordination, it offers benefits at every level of our health care system. But that means mistakes can reverberate through the system, too.

It doesn’t matter if you’re a patient, a doctor, a clinical coder or a CEO. It doesn’t matter if a patient’s medical record is paper or pixel, or whether it’s being lifted out of a box in a hospital basement or accessed from thousands of miles away via an app on a hospitalist’s smartphone. No matter how quickly you can get it, the information is of no use if it’s wrong.

Abby Norman is a science writer based in New England and the author of Ask Me About My Uterus: A Quest to Make Doctors Believe in Women’s Pain. She hosts a daily podcast on Anchor.fm called “Let Me Google That.”

ALSO ON HUFFPOST OPINION

Give Mothers — And All Women — Space To Talk About Their Pain

Mental Health Awareness Can’t Be Just For Rich People

How Jackie Kennedy Normalized Cesarean Section Births

This article originally appeared on HuffPost.