Mind the generation gap in Calgary's debate over zoning and townhouses

It was gearing up to be a battle for the ages: Calgary's big rezoning debate over permitting fourplexes in any and all neighbourhoods in the city, with hundreds of speakers expressing opinions across more than a week of hearings at city hall.

It has often appeared as a battle of the ages. It's hard not to notice the generation gap between the Calgarians fighting for the change, and those fighting against it.

One didn't even need to step inside city hall chambers or flip on the hearing's livestream to see the apparent differences.

In the plaza outside city hall on Monday morning as the public hearings began, a few dozen community association activists from the city's various corners wagged signs and sported black-and-white buttons that said, "NO Blanket Rezoning YYC."

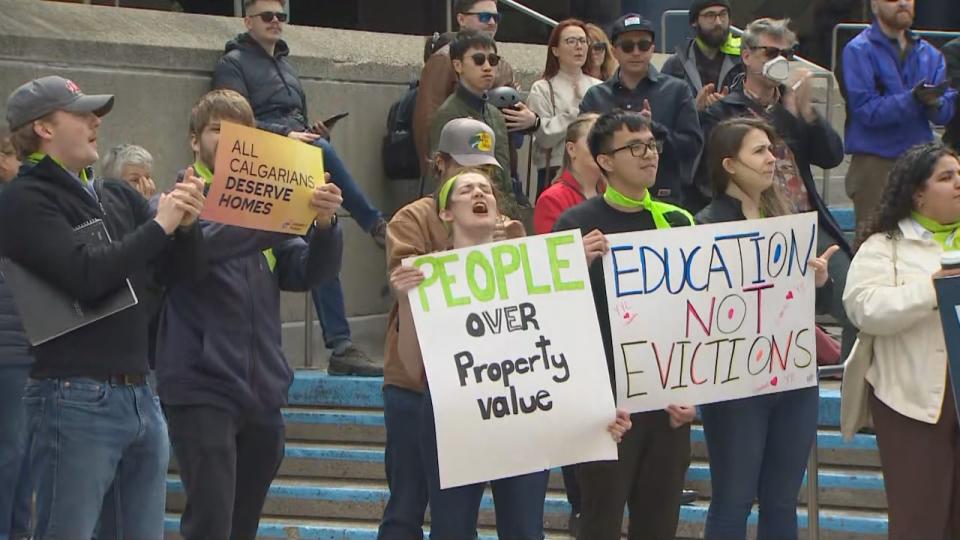

At noon that day, another crowd gathered to demonstrate in favour of the measure recommended by Calgary's affordable housing task force, many carrying a political action group's placards saying, "All Calgarians deserve homes."

This was a noticeably younger group, more millennials and Gen Zs.

The crowd was noticeably younger at the rally in favour of the rezoning that was recommended by Calgary's affordable housing task force. (Mike Symington/CBC)

As the debate unfolded, one could crudely split the debating lines into younger or older, or into the haves and have-nots. The divide is between those who have and don't have homes they own.

Many Calgarians opposed to the plan were homeowners, worried about the zoning that could come to their own neighbourhoods, if one could develop duplexes, townhouses or row houses in almost any residential district.

They expressed worry that more density amid their standalone houses could clog their streets with traffic, parking, recycling carts and tall skinny homes — while ripping out old trees and overburdening nearby schools in the process.

The residents who support citywide rezoning often aren't homeowners, but hope to be. They'd like more of a chance to join those neighbourhoods the others are scrapping to preserve as is, without the potential upheaval of subdivided lots for extra homes.

Disruption? Change? Potential for struggles to find guest parking on one's block? "That doesn't supersede the need to have a roof over our head," Alex Williams said in an interview.

He's a 28-year-old who rents an Acadia house with three roommates, and recalls having to couch-surf for months with friends and family until he found a place.

"The idea of being homeless with thousands of dollars saved seemed insane," he said. The idea of finding a home to buy? Seems nice, though he understands why homeowners who've had what they've had for a while are less amenable to change in their neighbourhoods.

A man's zone is his castle

One speaker was rankled by the very fact that renters were injecting their voices into this debate. Others who came out in favour of rezoning warned of the disproportionate privilege of older homeowners who bought property well before prices spiralled out of reach for many.

The age gap was so pronounced to some speakers that one older southwest homeowner made a point of saying she wanted to "break the stereotype that every boomer is opposed to rezoning." She supported expanding options to build small multi-family developments in communities like hers.

At stake in this debate, in essence, is the abolition of R-1 zoning, which only allows detached homes, and is the dominant neighbourhood mode in Calgary.

Instead of R-1 or R-2 (which allows duplexes, too), the default district would be R-CG — the grade-oriented infill district. It would allow townhouses or row houses, up to four units on a 50-foot lot, plus potentially basement suites and even backyard units — totalling eight or 12 dwellings where a single bungalow currently sits.

Other municipalities in Canada and elsewhere have moved to end what planners and housing advocates call "exclusionary zoning," to allow lower-cost, more compact units to enter more homogeneously single-family districts. In plannerspeak, it's also the "missing middle," in between highrise apartment towers and bungalows — a family-friendly housing option that sensitively adds density in neighbourhoods.

The prospect is, to many residents, not sensitive at all.

"Please don't devastate the character of our great single-family communities," Guy Buchanan urged council at the hearing.

He's a retired housing developer, and insists there is plenty of land at Calgary's fringes where council should focus growth, instead of in established neighbourhoods.

Others argued that the city should instead focus on condos around transit stops and major streets, or developing on vacant city land.

The rub is that city hall is working on those solutions in tandem as part of its strategy to fight surging rents, homelessness and the affordability crunch that has pushed so many Calgarians out of the home-owning market, or into precarious situations.

The city stresses it's taking a "pull-all-levers" approach, and that this is one of those levers.

"No single action strives to or will on its own solve the housing crisis," said Debra Hamilton, director of community planning, at the hearing's outset.

The rezoning pitch, however, is the housing solution that shows up on residents' very own blocks, or right next door. Or, at least, it could.

It instills worry in some that tony Elbow Park will morph into Marda Loop, buzzing with infills and requiring large utility infrastructure upgrades. Or neighbourhoods by universities will become bigger magnets for investor-developers instead of the more conventional family home-buyers that older neighbours are used to.

One longtime Brentwood community activist showed off a picture of a row of several three-storey homes, and fretted about potentially having those residents able to peer into her backyard. A perennially in-demand neighbourhood for student housing, there's concern among neighbours there that developers will keep rushing in to further change it and make it more congested.

A younger Calgarian might say: but those tall windows would now be lit by more people who could afford to buy into that community, or rent there.

An example of row housing in Calgary. (Robson Fletcher/CBC)

In northwest Calgary, the median price for a detached home is $761,000 this year, according to the Calgary Real Estate Board. For a row house, it's $477,000.

And that's a world that has changed so much over the decades. In 1990, the average Calgary detached house cost $131,000. The median price for standalone houses sailed past $200,000 in 2002, broke $400,000 in 2007 — and then came the pandemic. In the last four years, that price has shot up by about 50 per cent to $718,400 this March, for the typical detached house, which remains the most plentiful housing type in Calgary, and the only offering available in much of the city.

Some homeowners fretted that this zoning change would sink their property values. After this much increase, that might sound like sweet music to those young Calgarians for whom a $700,000 house, its down payment and monthly mortgage costs, remain far out of reach.

A common argument came from residents opposed to this change: what's the point, if tearing down an old house and replacing it with a few brand-new townhouses or fourplex units won't actually create anything remotely classified as affordable housing? (And yet, so many of the critics also worry these new homes will bring crime and ne'er-do-wells into their midst.)

The response from advocates is that it all adds supply to a supply-starved, demand-heavy and rapidly growing city. More homes of all types will help keep increases in check.

Also, the truly "affordable" housing options are government subsidized. These developer-driven infill projects create more affordable options than single-family or duplex homes, without a taxpayer-funded backstop.

There are heavy echoes of last decade's debate that allowed secondary suites in all Calgary residential zones — now, instead of each proposal needing council's explicit approval, it's a quicker bureaucratic process. And whereas secondary suite pleadings used to take up a huge amount of council's time, now nearly half of public hearings are dedicated to one-off row house, townhouse or duplex rezoning proposals.

Advocates say reform will end red tape, while opponents of R-CG say it denies the public a say in how their neighbourhoods change.

The suite revolution that opponents had feared (and some housing advocates may have hoped for) failed to materialize, because suites have cropped up more gradually. But the new zoning could wind up bringing more aggressive redevelopment because suite development is often a homeowner's own chore, compared to the more developer-intensive (and investor-attractive) project of building new fourplexes or row houses.

One issue raised by critics was that construction labourers, already scarce, will be diverted from larger-scale unit building to focus on these relatively smaller neighbourhood projects with higher per-unit costs.

Boomer and bust

Coun. Jasmine Mian says this debate appears to have the biggest generational divide of anything she's handled in her first term on council, the young pushing for housing choice and change, and older homeowners concerned about the future of their property asset and how congested their neighbourhoods might get.

"It is a battle of generations that I think is going to put council in a very interesting position about what do we do for the future of our city," said Mian.

Coun. Jasmine Mian, who has said she favours making neighbourhood infill approvals easier, says she hasn't seen such a clear generation gap before on an issue that's come to council. (Submitted by Jasmine Mian)

She, along with Mayor Jyoti Gondek, are among a slim majority on council whose past votes suggest they'll likely support rezoning — and many, like Mian, are among the youngest councillors.

However, at the public hearing's end, several councillors will propose amendments to modify the proposal, either to delay its effect or otherwise soften its impact, to make the change more palatable to reluctant constituents.

One senior planning official, offering up a compromise, told council this week the department would be fine excluding backyard dwellings from the potential mix in fourplexes that already have basement suites, eliminating the prospect of 12 dwelling units on a one-bungalow lot. Only up to eight.

Any result is bound to be controversial, among one demographic or another. It has tended to be the older anti-reform residents who've warned about the potential blowback councillors may face in the 2025 civic election.

After all, tradition tells us that it's older, home-owning residents who are most likely to vote.