Mimic Octopus Makes Home on Great Barrier Reef

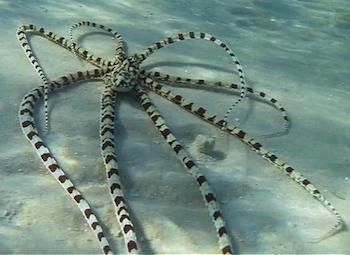

Of all the amazing octopus species out there, the mimic octopus, Thaumoctopus mimicus, is perhaps the most bewildering. While most known octopuses are able to change color and shape for camouflage, mimic octopuses can also impersonate other animals to deter would-be predators. They can contort their bodies and long, striped arms to look--and swim--like other (less edible) sea life, including lionfish, sole and banded sea snakes.

These implausible creatures were only first discovered by scientists in the 1990s in Sulawesi, Indonesia. Since then, the mimic octopuses have been found in various waters around that island country, but not too much farther afield. They are generally active during the day but live primarily on obscuring sandy or muddy sea floors--down to about seven meters.

But these odd octopuses have now made a confirmed appearance on Australia's Great Barrier Reef, more than 2,000 kilometers from where they were first described. Divers had reported sightings of these strange cephalopods in recent years, but Darren Coker, a researcher at James Cook University's ARC Center for Excellence for Coral Reef Studies, verified this species' presence there, in a report published online earlier this month in Marine Biodiversity Records.

Coker spotted the octopus on a shallow sand flat near Lizard Island during a super low tide on the afternoon of July 4, 2012. The adult octopus's body measured roughly 10 centimeters, and "it appeared to be in distress," Coker reported in his description of the encounter. But, never fear, it "recovered quickly once moved to slightly deeper water."

Coker was then able to follow the octopus for about an hour as it swam about and showed off some of its impersonation skills, including one phase swimming like a flounder. While at rest, it spread its arms out wide, perhaps to make it look bigger to ward off potential predators.

"This sighting extends the previously documented range down into the Great Barrier Reef, suggesting [its range] is much larger," Coker noted in the report. "This species may simply not have been recorded because of its cryptic nature or unexplored habitat (commonly found in muddy and sandy substrate)."

This animal's presence on the Great Barrier Reef also suggests that the reef itself is home to even more exotic animals that we previously imagined. "The Great Barrier Reef may contain many more undocumented species from the Indo-Pacific region," he noted. "But due to the limited familiarity...new species are going undocumented."

Follow Scientific American on Twitter @SciAm and @SciamBlogs. Visit ScientificAmerican.com for the latest in science, health and technology news.

© 2013 ScientificAmerican.com. All rights reserved.