Mid-Valley history: Anti-Catholic legislation changed public education 100 years ago

In the midst of back-to-school ads this past month came a news story about a new publicly funded virtual charter school in Oklahoma. Listening to the description of the school administered by the Roman Catholic Church and the subsequent lawsuits, I couldn’t help but think of examples close to home of collaborations between public schools and the church in our not-too-distant past.

In Marion County just a hundred years ago, the supposedly clear lines of delineation between church and state in public education were often blurred.

Up until the passing of the so-called “Garb Law” in 1923 (garb being a somewhat flippant term for clothing), nuns in full habit regularly served as public school teachers in Marion County — especially in the more rural Catholic-majority communities of St. Louis, St. Paul, Sublimity, Shaw and Mount Angel.

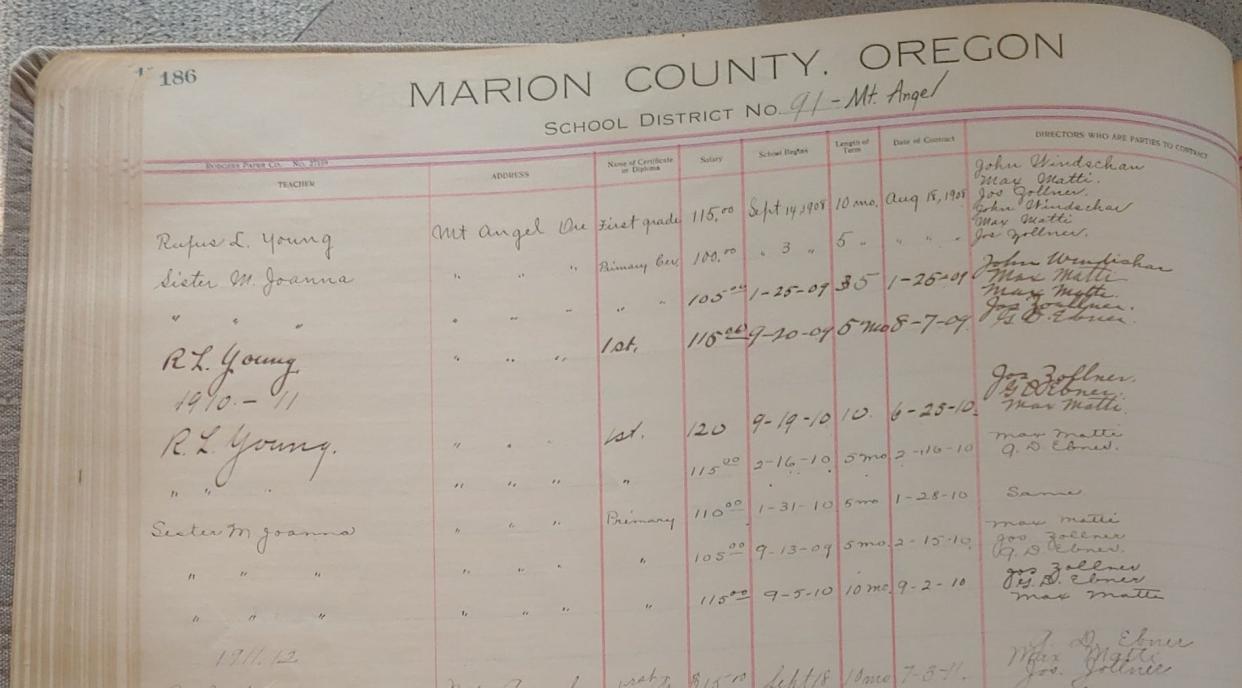

The title Sister makes its way onto many pages of a ledger tracking teacher contracts made by Marion County school officials from 1910-1914 now housed at the Willamette Heritage Center. The ledger also shows that each district’s school board had direct oversight of the hiring of teachers, which may explain some of the practice.

It was so prevalent in the state that it caught the eye of the Legislature, at the time heavily influenced by the anti-Catholic Ku Klux Klan. In addition to passing a compulsory public education act targeting parochial schools (which would later be overturned in the U.S. Supreme Court), the Legislature passed a bill banning public school teachers from wearing any religious garments, effectively eliminating Catholic nuns from eligibility.

The so-called “Garb Law” went into effect May 24, 1923, causing a bit of a scramble by public schools employing nuns to either to finish their terms early or find substitutes.

Marion County Schools Superintendent Mary L. Fulkerson toured the schools prior to implementation of the law to study its effects and noted: “It has been unanimously agreed that they [the nuns] will abide by the law. By this, however, is meant that they will cease teaching in public schools after the garb law goes into effect, rather than remove their garb. There is nothing, however, to prevent them from teaching in private schools.”

In reference to the law, one paper suggested that the effect of removing religious influence in the schools by this law was probably not going to happen, because “it is thought more likely that the school boards will appoint Catholic teachers who are not nuns to take their places.”

It is hard to tell how much that happened.

In Mount Angel, however, the community got creative and brought the nuns back to their school by converting the lower grades to a private school, an arrangement that persisted until 1967.

As a side note, the garb law stayed on Oregon’s books for a long time, despite a 1986 Oregon Supreme Court challenge by a Sikh teacher in Eugene who had been fired for wearing a religious head covering. The law was overturned in 2010.

Collaboration between public schools and religious organizations extended beyond just personnel.

In 1920, the new public school building in Mount Angel was built by the Catholic Church. St. Mary’s Public School was hailed as a model of efficiency and resourcefulness — combining community resources to create a state-of-the-art school facility.

“While the building belongs to the Catholic society in Mt. Angel, which was wholly responsible for its construction, it will be under the supervision of the county superintendent and is purely and wholly a district [public] school,” the Capital Journal newspaper reported just before its Thanksgiving opening in 1920.

The first principal of the school was Sister M. Agnes (Rose) Butsch. She was a Mount Angel local, having moved there at age 8 and taking her vows at age 16 in the local convent. Her 55 years of religious life were devoted in large part to teaching.

The partnership between the church and the school district persisted into at least the 1980s, although by that point the relationship had been formalized as the district leasing the school building from the church. The district hoped to eventually purchase the building. The church desired a joint ownership solution.

The 1993 “Spring Break Quake” shook things up and destroyed the 1920 building. A 1995 bond effort rebuilt the school and secured the property ownership to the Mt. Angel School District.

The rebuilding project also brought calls to rename the school.

But after much debate, the efforts did not meet with success. St. Mary’s Public School continues to operate as such today, a fully public school with a name rooted in its religious past.

Kylie Pine is curator at the Willamette Heritage Center, a 501(c)3 nonprofit museum in downtown Salem dedicated to gathering, preserving and sharing Mid-Willamette Valley History. More information at www.willametteheritage.org

This article originally appeared on Salem Statesman Journal: How anti-Catholic legislation changed Oregon public education