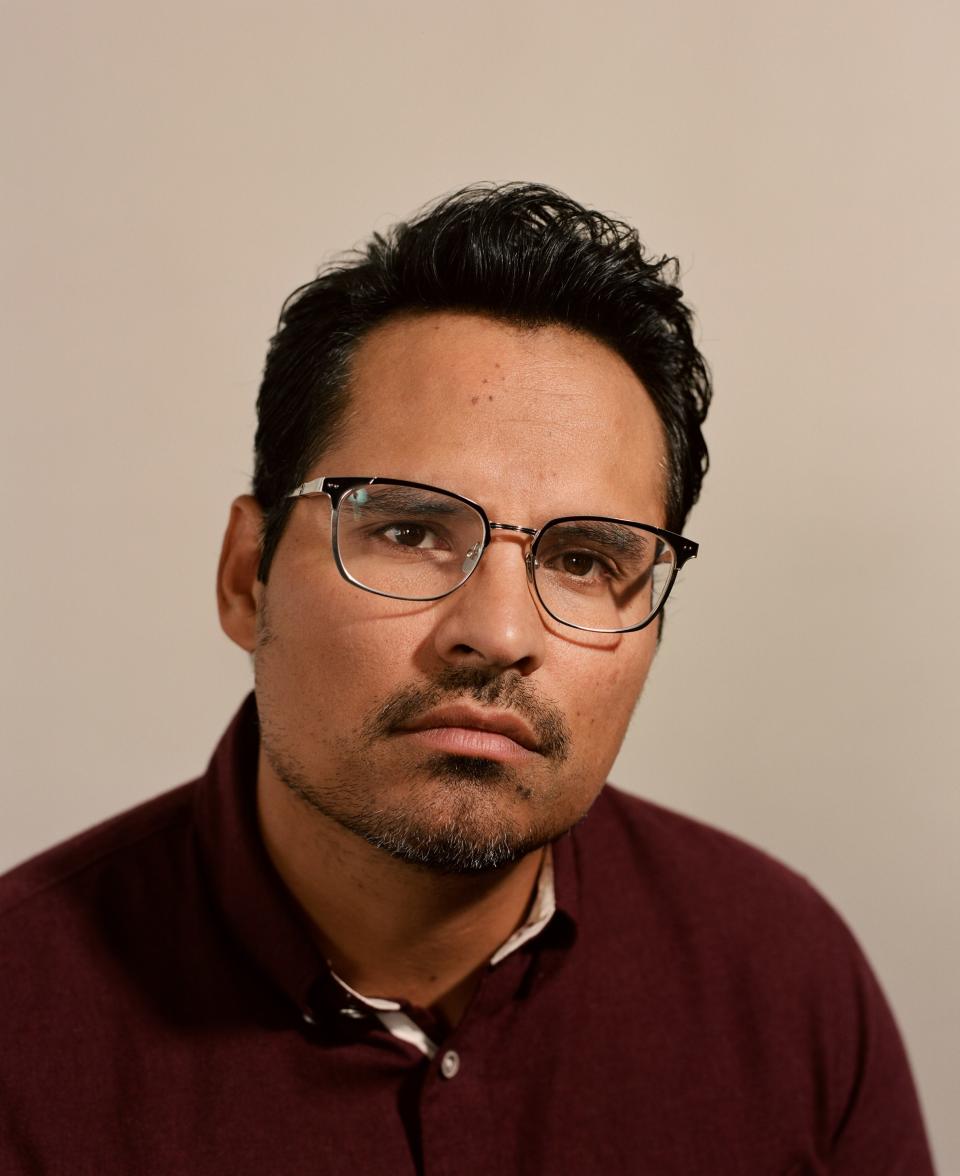

Michael Peña Has Come to Play

1.

Michael Peña isn't quite sure why I'm talking to him. He thinks I want to hear him talk about Paul Rudd, or Jake Gyllenhaal. He tells his wife the same thing—Peña doesn't think he's one of "the typical GQ guys," like, say, Bradley Cooper. (He loves Bradley Cooper. He just saw A Star is Born and says it's “gonna knock you on your ass.”)

Just so there's no doubt: Michael Peña has been around the block. He's been working in Hollywood for over twenty years, a film career that includes notable parts in back-to-back Best Picture winners (Million Dollar Baby and Crash) and two Marvel films. He was the drummer in a band (Nico Vega) for a spell. He's done TV both large (he had a nearly season-long arc on the acclaimed drama The Shield, and he's about to star in Narcos: Mexico, taking over for Pedro Pascal) and small (one of his earliest roles was on Felicity, obnoxiously hitting on Keri Russell, his "University of New York" R.A.). But in a situation like this one, where there's nothing to discuss but him, he doesn't quite know what to do.

We're at The 101 Coffee Shop, a '60s-style diner in Hollywood where the music is about as loud as the decor (too loud). The diner's website notes that it was in Swingers, but I won't find this out until later. Otherwise I'd have asked Michael Peña about Swingers. Instead, I ask him about golfing.

That's our plan for tomorrow. We're going golfing, because he loves it. I tell him that I've never golfed in my life, because I think it's the polite thing to do.

"Are you serious?"

I’d actually told him before. He must have forgotten, and I never stopped to consider that golfing with someone who doesn't know a thing about it might not be terribly fun for either person. But Michael Peña is a gentleman.

"Just like in acting, or in any business," he says, chuckling, "there's always a way in."

He follows up: "Are you good at sports?"

I tell him that I'm athletic enough, which is a good way to tell the truth without answering the question.

"I find golf is probably the hardest sport that I've played, because it takes a lot of timing," he says. "I grew up boxing, playing football and wrestling, all that stuff.” Dude’s always loved sports.

I ask him how it felt learning to golf, since it's something I've always felt too self-conscious to really try. In my experience, most golf players are of a certain inclination (white) and once you notice that, anything more extreme than Pirate's Cove Adventure Golf in Orlando starts to feel a bit odd. He says it didn't occur to him much, because he took it up on the set of 1996's My Fellow Americans, starring Hollywood legends Jack Lemmon and James Garner.

"That was my first movie!" he says, still amazed it happened. "I got it like three months after I got to L.A., so I thought I was so lucky to get it. And [Lemmon and Garner] were always talking about golf, and so it's something that I do now. When you're off doing a movie and you're working four to five days a week and you have a weekend by yourself—what do I do on the weekends? So I'm like, alright, golf, so I don't drive myself crazy."

It was also a sport he could play solo while out on long shoots—a way to think, work out a character he was going to play. And it didn't hurt that in the mid-'90s, golf was cool, thanks to the meteoric rise of Tiger Woods.

"I saw Tiger Woods on television, and I thought, Wow, that guy looks completely different than any other guy playing golf. Before it was, like, middle-aged men that were not in good shape. This guy was a complete athlete. He had every shot. He had power—it was almost like a really good basketball player, when they can go to the hole really hard? But then they also have that touch in the end, once they're by the hoop, posting up."

He compares Tiger to Jordan, elevating the game. Or Brando, to bring it back to acting. ("To me it's always acting and sports," he says with a grin.) It was a shift he compares to the first time he saw Latinos on TV—his mom, concerned about the number deaths in the neighborhood, sprang for HBO and cable television, hoping it would help keep her two sons indoors. And it did, at least mostly. Peña describes how he and his brother would imitate the people they saw on TV, extending dramas they watched into dramas they were in. He tells me about seeing Esai Morales in La Bamba, John Leguizamo in Mambo Mouth.

"I remember watching [Leguizamo]. I was in the living room with my brother. It was so funny, but so sad, and I couldn't believe that there was a Latin dude with permission to talk about our lives."

2.

So we're golfing, and Michael Peña is singing the hook from Cardi B's "I Like It,” which is the chorus from Bronx-born boogaloo singer Pete Rodriguez's 1967 song "I Like It Like That," re-recorded in 1994 by Puerto Rican bandleader Tony Pabón for the soundtrack to I Like It Like That, Darnell Martin's indie film about Puerto Ricans in the South Bronx. As we walk across the green, we talk about Latinx actors that have won Oscars. There aren't many. We do some googling, and learn that Rosie Perez was nominated once. We wonder what she's doing now that the NBC drama Rise is no more, and what movie she got her Oscar nomination in. (It was Fearless, the 1993 Peter Weir film, Siri says.) The Latin diaspora is vast and complex, but Hollywood barely has a clue.

Peña doesn't really look like he’s about to golf. He's wearing an outfit similar to the one he wore to the diner the night before: a graphic tee with a perforated square and scissors on it; a hat with a Silver Lake patch; dark hi-top Nikes; shorts; nice-looking prescription sunglasses, subtly polarized. I'm dressed like a dummy, wearing a collared shirt and long, dark pants in the middle of a heat wave. We share a caddy that's smaller than I expected. It houses the clubs Peña got for his son, Roman, he explains, holding up a small glove left in the bag. He doesn’t have his set because ants got in all his gear.

We go through a bucket of golf balls at the driving range and he teaches me to swing. Strike the ball on the opposite side I want it to fly. Don't go for power, just make contact. Swing like I'm swatting the ball with my left hand. The lanes—if that's what they're called—are pretty full, with only about three open slots. Most everyone looks like golfers (white). Except us. And the people working there.

As I learn how to get started in golf, I also learn how Peña got started in Hollywood. He'd get the character breakdowns for casting calls, and they barely had any room for someone like him. "Ten characters would be Caucasian, Caucasian Caucasian, which I was like, Whoa, dude, I don't even know if that's legal, you know?" he says. "And then the 10th character would be, you know, African American—then the 13th role would be open to other races. I was like, 'Dude, I'm fighting for 13th place.'"

He doesn't seem angry about this, at least not anymore. Despite the deck being stacked against him, for Peña, it's all about the work, and not much else. And it was hard work. But it's all hard, and he seems to have the same frank, resigned approach to it all, telling me about the first time he saw a gun (he was eight), how he lost his first bike, robbed after having it for 30 minutes. That's just life.

Being in Mexico for the last eight months while filming Narcos was strange for him. He's got family there, but after his parents immigrated, they didn't have papers until he was 12. For most of his youth, visiting Mexico had been out of the question whenever he brought it up.

"I was like, 'Mom, do you want to go to Mexico?' and she was like, 'If you want to go, we have to stay [in Mexico].' So we decided to stay in Chicago." After she passed away years later, he lost his biggest tether to the country he came from. It didn't help that growing up in the States has a way of alienating you.

"You know what's funny, man?" he says. "As soon as you get to Mexico, they're like, 'You're American.' And over here, they're like, 'We're Latin.' You know what I mean?"

3.

In golf, a "birdie" is a term used to describe a score that is just one stroke under par. So on the small, beginner's par-3 course Peña has taken me on, scoring a birdie would mean sinking it in two strokes. Halfway through our nine-hole course, Michael Peña is trying hard to sink a birdie. That's when I ask him about Scientology. He talks about it the way he talks about a lot of things in his personal life: sparingly, with a mild level of discomfort.

"It's like if I was a Catholic—I'm Christian too, and nobody asks, ‘What about like, Jesus? Are you a big fan?’" he says. "It's such a personal thing. [Scientology] works for me. You know, there's people that are like Buddhist? I don't ask people about that."

I tell him I get it. It's just that I've never really seen or known of anyone that looked like me involved in Scientology. I want to know what that's like, if he finds it bleeds into his life and values the way Catholicism has woven itself into Latin culture. He's amenable, but he doesn't budge much.

"How do you describe religion to somebody, you know?" he says. "Like Catholicism. If you were to explain that to somebody, you're like, Wait a minute. What? You believe in a guy that what?"

He tells me to check out the website, and then apologizes for not having much to say to me about it all.

"I don't even talk about it with my friends," he says. "It just never comes up."

He doesn't sink the birdie.

Walking from one hole to the next, we move on to topics more mundane. He asks me to explain Fortnite and Minecraft to him, video games his son loves playing and watching YouTube videos about. He brings up his love for true-crime series like The Staircase. At one point I ask him for a dinner recommendation and he isn't sure what to say. He likes eating at home.

"I feel like I'm not a very exciting person," Peña says. "At least, not in activities. I like golf, chess. I like spending time with my family, reading a lot, you know?"

We spend some time talking about comic books. Despite his history with Marvel, superheroes aren't really his his thing. His tastes—edgier fare like Garth Ennis and Steve Dillon's Preacher, or the literary graphic novels of Adrian Tomine—make a lot of sense when you learn that it was Seth Rogen who turned him onto comics on the set of Observe and Report.

He's got a bunch of little stories like this: picking up Intelligentsia coffee to aggressively chug before sparring sessions with Jake Gyllenhaal for End of Watch, waiting for Brad Pitt to ditch the paparazzi with his Fury castmates for their first table read. ("This son of a bitch looks like he's entering and traveling via segway, with the fuckin hair blowing out. He's the only dude to make an entrance in slow motion in real life.")

Peña describes what it's like to be stuck in a tank with all those guys—Pitt and Jon Bernthal and Shia Labeouf and Logan Lerman, in freezing temperatures, beat the hell up.

"You just go crazy, dude," he says. "I remember, for Fury, [director] David Ayer—I don't know if he likes method acting, but he definitely likes commitment."

David Ayer's movies—of which Peña has starred in two—are best known for their harsh and aggressively masculine aesthetic. They're movies about as bleak as Peña is friendly.

"I've been told I make chick flicks for guys," David Ayer tells me. "I mean [my movies] explore male relationships and friendships and what do those look like and then what the effects of violence and trauma have on people, how they process through their friendships and family."

It's the sort of thing Ayer told me Peña (whom he would often direct in Spanish, even if none of his castmates understood it) was uniquely suited for. "The guy, you know, he's a beast and one of those actors that other actors have a lot of respect and fear for. Because when he's locked on, he can run circles around people."

Peña describes much of his acting as imitation, caricatures of people he's seen or known. He attributes this to his older brother, always the storyteller, the life of the party, acting out his high school escapades.

"It was like hours, just watching him," he says. "So I picked it up from him. And sometimes it was way easier to imitate than to communicate."

4.

Michael Peña's greatest weapon might be his smile. It's both impish and innocent at the same time. If you're paying attention, it can turn you into a conspirator, in on a joke. If you're a less-observant chump, you might mistake it for naiveté. Let me tell you what I mean:

We're on our way out. Near the parking lot, he spots an older, familiar looking guy in a baby-blue polo and white shorts. He grins at me. "You know who that is?" he asks. I’m unsure of whom he's talking about. "That's Jon Lovitz." He googles the name to pull up a picture so I can match it to the person a few yards away. It is Jon Lovitz. I think that's the end of it, just another example of how, after over twenty years, in the business, Michael Peña is still just a huge fan. But no. Jon Lovitz is in the parking lot, and Peña wants to say hello.

"Jon Lovitz!" he calls out. "What's up man? It's Mike!"

"Oh hey, how are ya?" Lovitz says. "I saw you in another movie! You never work."

"Yeah, I know"

"You're only in every other movie. What did I just see you in? Wait, don't tell me. I know," he says. "I hate people who—I have a joke about that: You're Jon Lovitz? 'Yeah.' What have I seen you in? 'I don't know! I'm not you!'"

They go back and forth with the bit for a few minutes, talking about the extremely Hollywood problem of helping someone else remember why they think you're famous, naming off movies for them to no avail. Throughout, Lovitz tries to remember the last movie he saw Peña in.

"We were at a strip bar and this comedian, he's very funny, he goes 'What have I seen you in? Gone With the Wind?" Lovitz stops suddenly, and throws another movie at Peña. "Star Wars?"

"Oh, I did that one. I was the lead in that."

"Wait. Don't tell me—God damn, well you really.... fuck. It's out now! Was it Mission: Impossible? Goddammit it was a comedy. Game Night?”

"Nope." Michael grins at me.

"What the fuck was it? You had a business with the three guys? And then at the end—it was like a science-fiction film, kind of. The business succeeds. It's three of you and two of the guys are really dumb in the office. They have accents. You know which one I mean?"

"Yup."

"You do, don't you? Fuck! I think I saw it on a plane. Does that make you feel better?"

Peña laughs. "You saw it for free?"

"No, but you're always great! You are!"

"Aw, thanks man!"

"Your range is ridiculous! From comedy to like heavy, heavy drama—the police one where you get killed? Yeah, that was brutal—OH! Wasp and the Ant-man?”

When he finds out I'm writing about Peña, his voice takes on a theatrical affectation.

"I remember when Michael came to my acting class. He was a very raw talent," Lovitz jokes.

"What did you teach him?" I ask.

"Anything he doesn't know."

5.

If you take a moment to consider Michael Peña's career, you might notice something: He only plays Latinos. Or maybe you won't notice. It's not like he enters a movie draped in the Mexican flag, lecturing people on his culture's history. He just asks to change the characters' names. Rick Martinez. Father Lozano. Mike Zavala. Sometimes, filmmakers do it for him, and he doesn't even have to ask.

"It's a small thing, but I remember John Leguizamo, who I thought was Italian, out there speaking Spanish and I was like, 'Oh damn.' Or Esai Morales. Stuff like that, especially when you're younger, they really fuckin inspire you, man. They still stick with me to this day—Esai Morales going “RITCHIIIEEE!”—because I had a brother, that really affected me! And the fact that I knew that was Esai Morales"—he stresses the accent. There's no lingering on the O, a soft tumble on the R, the S rests on his tongue—"you know, like, the Latin dude? Wow, man."

But when he got to Hollywood, he found that the industry wasn't really in the business of inspiring Latinx kids. He was, like many actors of color before him, advised to change his name.

"I saw that some people would change their name, and they would get commercials," he says. "I just thought it was a slap in the face… Because I did deal with racism as a kid. So it felt like changing my name would be kind of like conforming. I'm not really down for that. I know that my parents, they crossed the border to offer us a great life. And I didn't want to turn my back on my dad working two full-time jobs, my mom working two full-time jobs, so me and my brother could go to private school. So I never considered it. It could've been easier, maybe. Maybe in the beginning."

In a piece for The Ringer, Shea Serrano reflects on Peña's long rap sheet of characters that are Latino, but whose existences aren't solely defined by being Latino. He is, according to Serrano, an incredibly rare thing in the world, and one that's vital for Mexican-American representation.

"That's as important as somebody out there with, you know, making a big campaign about it," Serrano tells me. "Michael Peña can do it. He can do whatever you need him to do. He's a guy you can point to and say, this is what an actor who is Mexican looks like when he doesn't have to only fuckin’ be Cesar Chavez in a movie. He can be the scientist. He can be the cop. He can be the locksmith. He can be whatever you need him to be."

Peña is humbled when I bring this up. "I'm just glad that people notice,” he says. “It's not like I think I'm this self-righteous dude, because I'm not. I wanna be in good stories. And I want other people, people like me, to know that there's a way out. You know?"

He wants me to know that it's a great time to be Latin. Consider his role as Rick Martinez in The Martian. "I played an astronaut, you know? With a Latin last name. Sometimes the story is just me in the astronaut suit. Sometimes that's reason enough to do a movie." He repeats what I'm starting to believe is his motto, the same thing he said when we met and I told him I didn't know how to swing a golf club: "There's always a way in."

And I think I finally understand why Michael Peña took me golfing.