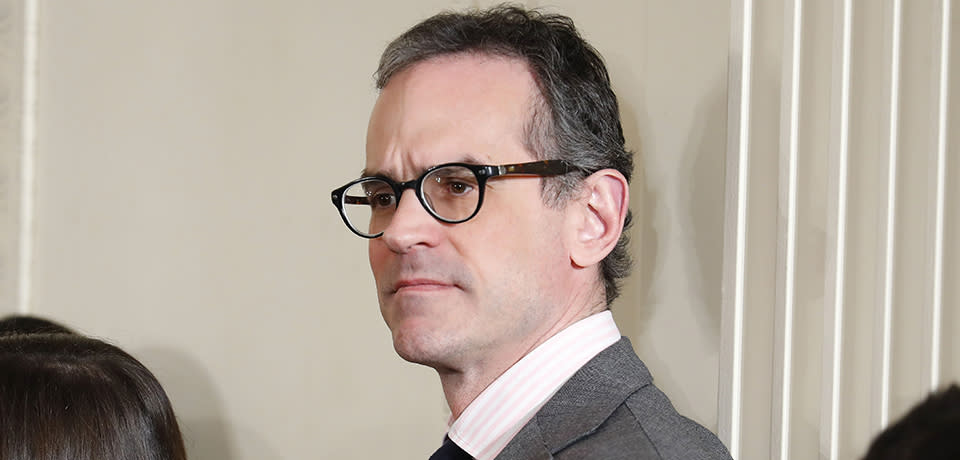

Michael Anton Is Donald Trump’s Ben Rhodes – But Is He Going Too Far in the Other Direction?

Is there a Trump Doctrine? And how will the liberal international order fare under the Trump presidency? Trump’s own pronouncements are difficult to parse. His major foreign-policy speech last year was largely campaign fodder, a stem-winder of invective against the foreign policy establishment and a defiant announcement of Trump’s “America First” approach. Aside from that, we have a regular feed of presidential tweets — and little else.

Thankfully, for those interested in understanding the administration’s foreign policy thinking, we have Michael Anton, currently serving as the deputy assistant to the president for strategic communications on the National Security Council staff in the Trump administration. Anton made a (pen) name for himself with a series of pseudonymous essays last year arguing in favor Donald Trump’s candidacy — most famously in the “Flight 93 Election” essay. Anton was attempting a sort of political ventriloquism, trying to articulate a better version of Trumpism than Trump himself. That Trump hired Anton as the mouthpiece of his foreign policy suggests Anton was onto something. His is a voice to heed closely in the age of Trump.

Anton has sallied forth again, this time under his own name, with an essay in the inaugural issue of the new nationalist journal American Affairs. Here Anton attempts to sketch the outlines of Trump’s emerging foreign policy. The essay is a provocative mixture of sharp queries, valid points, and a few assertions that I’d like to challenge.

Beware the Obama precedent

Anton complains that the foreign-policy establishment is intellectually lazy: that it has fallen prey to groupthink, given in to inertia, and confused means with ends. He believes that the establishment has failed to rethink first principles in light of changing circumstances and, as a consequence, failed to articulate why liberal order matters and how it serves American interests.

We’ve heard these complaints before. Every administration comes into power believing the previous team was incompetent and had messed everything up, and that the new team is burdened with the task of rethinking everything anew. Anton and his predecessor, Ben Rhodes, appear to share in common their indifference to “the Blob.”

Anton and his colleagues might be wise to take Rhodes and the Obama team as a cautionary tale. The latter came into office with a strikingly similar disregard for foreign-policy professionals. The Obama team appeared largely impervious to input or constructive critique for the duration of their time in office — and, partly as a result, left behind the very challenges the Trump team is now tasked with meeting. Whatever the failings of the “establishment,” their collective experience could help avert the most common failings of inexperienced administrations.

Liberal order’s defenders

Anton claims that “no one quite got around to saying what, exactly, the ‘liberal international order’ is,” and that its defenders “seem to think that no explanation of its utility or value is necessary.” He takes it upon himself to reconstruct the argument so as to point out its flaws. This is, of course, a rhetorician’s trick: Anton complains that his opponents are so hapless that they failed to make their case in anything like its strongest terms; so Anton, in his magnanimity, will have to make it for them before his can adequately refute it

Anton’s (and Rhodes’s) complaint is inaccurate. There are a number of impressive recent works that try to do exactly what Anton asks for — define, defend, and adapt the liberal order for a changing world. The best polemical version is Robert Kagan’s The World America Made. Probably the best academic version (and a far denser work) is G. John Ikenberry’s Liberal Leviathan. In between, more accessible yet also more philosophically ambitious, is Walter Russell Mead’s God and Gold. Or if you prefer something older and more theological, Reinhold Niebuhr’s Irony of American History and The Children of Light and the Children of Darkness are still solid.

These are giants whose work would benefit any student of international affairs. And they are giants on whose shoulders I stood for my own book, American Power and Liberal Order. In the book, I take up Anton on his challenge (well before he made it): I offer a definition of liberal order and a defense of why it is real, just, and important to U.S. national security: “American security and liberal order are mutually constitutive. Liberal order is the outer perimeter of American security.” And I try to work out the implications of adapting this grand strategy to the 21st-century security environment. For anyone lacking time to wade through all 300 pages, the National Interest excerpted the core argument.

A variety of thinkers have provided exactly what Anton has called for. Their extensive reflections and experience should be reassuring for an administration searching for intellectual ballast for its national-security worldview.

Seeking common ground

There is a surprising amount of common ground between Anton’s argument and ours. He rightly argues that the American public is mostly in the dark about the core of America’s interests and international strategy; that this is a moment for restating basic truths; that liberal order is a means for securing American interests; and that the liberal order, and America’s involvement in it, requires some evolution to keep up with changing circumstances.

Anton also rightly sees our alliance system as rooted in kinship with fellow democracies. However, he seems to favor democracies out of pure tribal loyalty. That’s not bad, so far as it goes, but there’s a substantially better and deeper reason than fellow-feeling for the democratic peace. Democracies tend to be more trustworthy, to keep binding commitments, to place more checks on their executives, to allow more transparency, etc. The United States’ longstanding preferential treatment for fellow democracies is founded on something more dependable than simply cheering for “our side.”

I say the common ground is surprising because I would not have expected so much commonality based on Trump’s campaign rhetoric. That Anton can acknowledge that the liberal order served America’s interests well during the Cold War, and that it “remains superior to most alternatives” today is an important point of agreement between the Trump administration and its foreign policy critics. It suggests some maturation of the Trump team from campaigning to governing.

Beware of Oversharing

Anton is also right that America constructed the liberal order as a means to serve its own interests, not as an end in itself. This is a complex issue, however: there is no necessary conflict between liberal order as a tool for American security and liberal order as an intrinsic good; and other states must believe in its intrinsic goodness—or, at least, its essential fairness to them—for them to buy into the order and make it function. That is why, despite American officials’ fundamentally selfish reasons for investing in liberal order, they typically stress its intrinsic goodness in their public diplomacy for foreign audiences.

That’s why Anton is unfair when he argues that foreign policy professionals “have forgotten—or never quite understood” the fundamentally selfish reasons for the liberal order. Anton is taking official pronouncements too literally, failing to recognize the multiple purposes and audiences at which such statements are aimed.

At the same time, he is not taking such pronouncements seriously enough: such statements are scrutinized by audiences across the planet to divine America’s intentions. Now that Trump is president, and Anton an official in his administration, their statements will be scrutinized and interpreted carefully. Anton should recognize that Trump’s campaign rhetoric and persistent Tweeting have sown doubt about America’s continued commitment to the liberal order, and Anton’s own writings may be looked at in the same light. Anton may be right about the nature and purpose of liberal order, but it may also be impolitic to be so open about it.

Put another way, Anton is right that prestige matters—but he seems unaware of the affect of the Trump administration’s rhetoric and early policies on the prestige of the United States.

Where the Rubber Meets the Road

Some of the weaknesses of Anton’s argument become evident as his gets more specific. Anton repeats what is by now an idée fixe for critics of U.S. foreign policy: the U.S. should not impose democracy by force, especially in places it is unlikely to succeed. This is a tiresome critique—entirely true, of course, but an irrelevant refutation of an argument no one makes. Insofar as it is meant as a shorthand critique of the entire post-9/11 era, it’s based on bad history that has little connection to the actual record of the Bush and Obama administrations.

The Obama administration discovered—too late, unfortunately—that the conflicts in Iraq, Syria, Afghanistan, and Pakistan are far too complex to be explained or managed by knocking down rhetorical straw men. After repeating for the umpteenth time that the United States shouldn’t impose democracy by force, you still have to have a foreign policy towards the Middle East and South Asia—something the Trump administration did not develop on the campaign trail and still lacks.

Anton similarly seems to misunderstand the nature of the challenge in Europe. He rightly recognizes NATO’s enduring importance but wrongly believes its “original purpose has evaporated.” NATO’s original purpose was, in Lord Ismay’s memorable phrase, “to keep the Russians out, the Americans in, and the Germans down.” Whether it is still necessary to keep the Germans down is for the Europeans to decide. But Anton’s dismissal of keeping the Russians out is a troubling continuation of the Trump administration’s underestimation of the challenge Russia poses to American security.

Anton also seems oddly concerned to criticize NATO expansion. He is over a decade late to this debate: there are no immediate prospects for further expansion. After Montenegro finishes accession this spring (it was formally invited last year), it will be only the third new member to join since 2004. Only one other state (Macedonia) has a membership action plan, and it has been dormant for nearly two decades. NATO expansion is a dead issue.

Learning to Disagree Honestly

Finally, Anton levels some unnecessary and unfounded accusations at his critics. He warns his readers that the foreign policy establishment will look down on and refute “any heterodox analysis” to protect its “guild,” in part because the foreign policy “priesthood” is on the take: it “operates and draws income from” the “constituent institutions” of liberal order. Anton believes that foreign policy professionals are incapable of honest dialogue because reasoned debate would threaten their livelihood.

This will come as a surprise to the foreign policy professionals scattered across hundreds of universities, journals, think tanks, foundations, government agencies, and consulting firms. It would be remarkable if every one of these institutions were a wholly-owned subsidiary of liberal order, in hock to a single agenda. On its face, it is simply not true that these institutions have anything like a common message or enforce message discipline on their writers. If anything, many of them build entire careers on disagreeing with each other.

More importantly, I hope Anton and his colleagues recognize that forums like Elephants in the Room (among many, many others) are open to a variety of perspectives and strive to debate with honesty and fairness. We’ll be open about our disagreements with the Trump administration, but equally honest about our common ground. If Anton wants that dialogue with his critics, granting their good faith is a necessary first step.

Photo credit: PABLO MARTINZE MONSIVAIS/AP