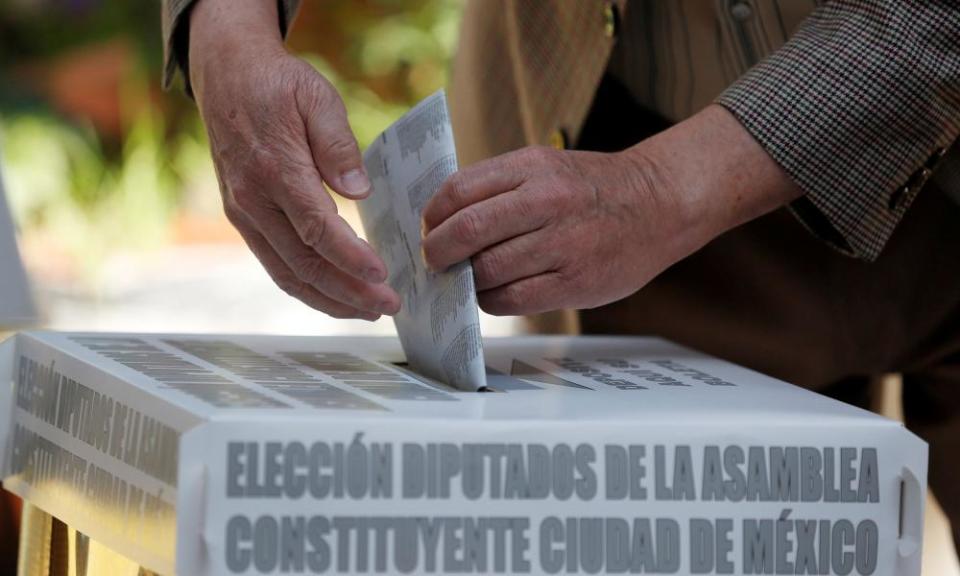

Mexican campaigns awash with dirty money, pre-election report finds

Anti-graft group says that for every peso reported to election officials, 15 goes unreported

For every peso spent by Mexican parties on campaigning and reported to electoral authorities, another 15 pesos goes unreported, according to a new study showing that the country’s political campaigns are awash in cash from dubious sources.

The report, published on Tuesday by the anti-graft group Mexicans Against Corruption and Impunity, comes four week’s before the country’s presidential elections. The left-leaning populist, Andrés Manuel López Obrador, leads polls for the 1 July election by double digits.

Mexican political parties are showered with public funding and electoral laws impose strict spending limits in election campaigns. But individual campaigns regularly race past those limits while illegal money can also come from corrupt local governments, businessmen buying future concessions and contracts, and even drug cartels.

Until 2000, the outcome of Mexican elections were never in doubt as the Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI) ruled uninterrupted for 71 years.

But according to the authors of the study, entitled Cash Under the Table, the advent of competitive, multi-party elections has increased competition and costs, especially as vices such as vote-buying persist.

Analysts say the cost of buying votes has ballooned in what has become a vote-sellers’ market, and poor voters sometimes view their suffrage as an asset.

Parties also spend enormous amounts to maintain patronage groups, which marshal the vote come election time.

“This is systemic. It doesn’t have to do with one party,” said Luis Carlos Ugalde, a former head of the country’s electoral institute and an author of the report. “Elections are more competitive so parties require more money.”

The exact scope of the spending is uncertain, though the authors pointed to troublesome signs such as an inexplicable increase in the amount of cash circulating in the economy prior to elections.

Parties break the spending rules because oversight is minimal, fines are modest, and the country’s electoral tribunal has issued rulings appearing to forgive egregious examples of campaign overspending, the report found.

“It’s a totally normal simulation, especially in gubernatorial races,” said Gerardo Priego, a former gubernatorial candidate for the National Action Party (PAN) in south-eastern Tabasco state. “In many cases, they check the small stuff and ‘don’t see’ the obvious and gigantic things.”

Political parties in Mexico can only collect private donations equivalent to a small percentage of the total public moneys they receive. Such policies were meant to keep out shady sources of funding such as narco money, but has ended up attracting rent-seekers and politicians with few ways of being held accountable.

“That’s why we have parties that don’t work,” said Federico Estévez, a professor at the Autonomous Technological Institute of Mexico. “They’re not responsive to society because they’re not dependent on society. All they depend on is the federal budget.”