Memories of John McCain, America's happy warrior

One night in February of 2000, John McCain arrived at a pier near the naval station in Bremerton, Wash., to find thousands of people waiting for him in the pelting rain. His speech was nothing special — McCain’s strength was always in the Q and A — but I’ll never forget one line he didn’t intend to come out this way: “Get out and vote for me on Tuesday, and I promise you, you’ll be happy.”

I never voted for John McCain, but I sure felt happy covering his electrifying though ultimately unsuccessful presidential primary campaign that year — happier than at any other time in decades on the politics beat. And so did the handful of other reporters and columnists crowded in a semicircle around him at the back of the campaign bus he dubbed the “Straight Talk Express.”

Younger reporters sometimes ask me if we were “in the tank” for McCain that year — blatantly favoring him over George W. Bush in the Republican primaries — and the answer is half-yes. We were professional and asked him plenty of tough questions, but the fact that we could even do so — 12 hours a day for weeks on end (more time than he spent with his staff!) — reflected a level of access he granted us that would dull the blade of the most vicious hatchet man. And he answered almost all of them honestly, even if doing so made him look bad.

Like the Kennedy brothers with an older generation of journalists, McCain appeared to enjoy our company in 2000, although the all-access press policy was also a stratagem to differentiate himself from Bush by running a nontraditional “maverick” campaign. He largely abandoned it in 2008, especially when his disturbing selection of Sarah Palin as his running mate vaporized his media halo. But McCain wasn’t built to hide from the press or be a blowhard. Donald Trump never apologizes for anything; McCain often did so, profusely, in part to seek media absolution for pandering or other unwise decisions. Of course there were limits to the contrition: He never said sorry for Sarah.

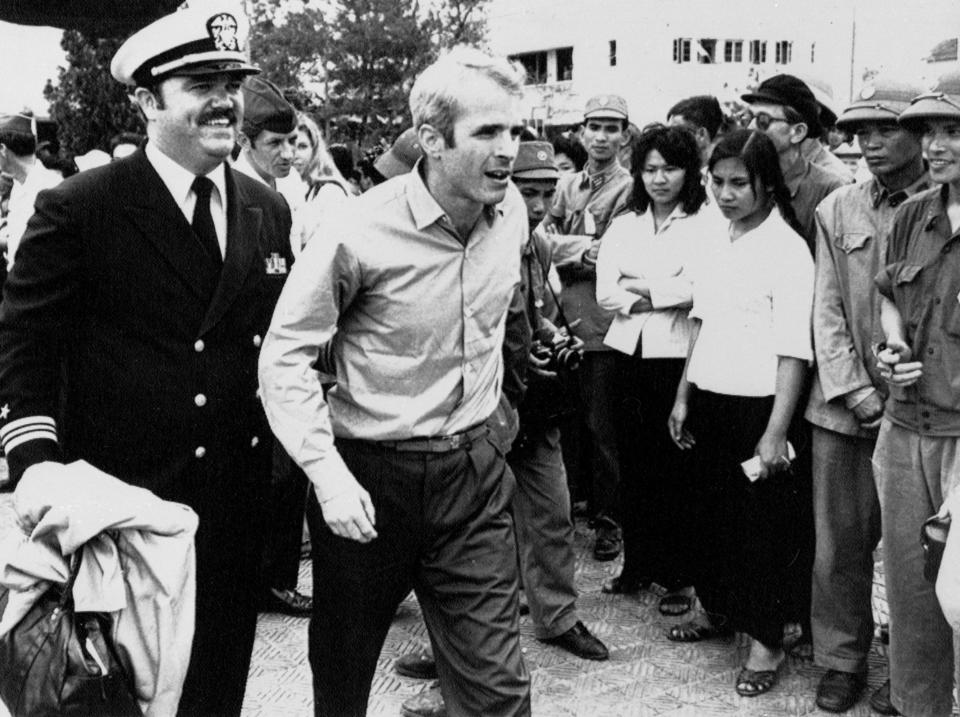

Up close, McCain was a throwback to that lovably irascible 1950s dad, the guy who told you to get off his lawn before offering you a beer and a war story you wouldn’t soon forget. That made sense considering that he essentially missed the 1960s. His five and a half years of captivity in North Vietnam — from 1967 to 1973 — coincided exactly with the souring of the national mood. McCain’s JFK-style “pay any price, bear any burden” ethic was closer to that of the Greatest Generation. When he said that he was running for president “to inspire a generation of young Americans to commit themselves to a cause larger than their own self-interest,” he struck a chord we rarely hear played today. Unfortunately, his conservative fiscal views prevented him from fully committing himself to a large national service program that might have been his signature achievement.

It helped that he was funny. “I’m Luke Skywalker trying to get out of the Death Star!” McCain liked to say in 2000, bounding on stage with a light saber, ready to do battle with a moribund Republican establishment. He joked that his wife said the only reason he was running was “that I received several sharp blows to the head while in prison.” On the bus, he described how he could tell dirty jokes in Morse code by banging a cup on the wall separating him from other inmates during his two years in solitary confinement. Standing before a dozen workers at a Michigan tech company one day, he responded to a conspiracy-minded question by saying simply: “And Angela Lansbury turned over the Queen of Diamonds” — a sly reference to the scene where Lansbury’s villainous character revealed her Communist coup plot in the 1962 film “The Manchurian Candidate.” McCain-hating rightwing nut jobs thought that movie, which portrayed a politician brainwashed during his captivity in North Korea, was practically a biopic, which both annoyed and amused him.

McCain never seriously attacked the press for “fake news” but he did tease liberal journalists in a way that was strangely fun. One morning live on “The Today Show,” McCain greeted me with a grin: “Good morning, Jonathan, you communist.” I smiled back and mumbled something about how he often calls us that.

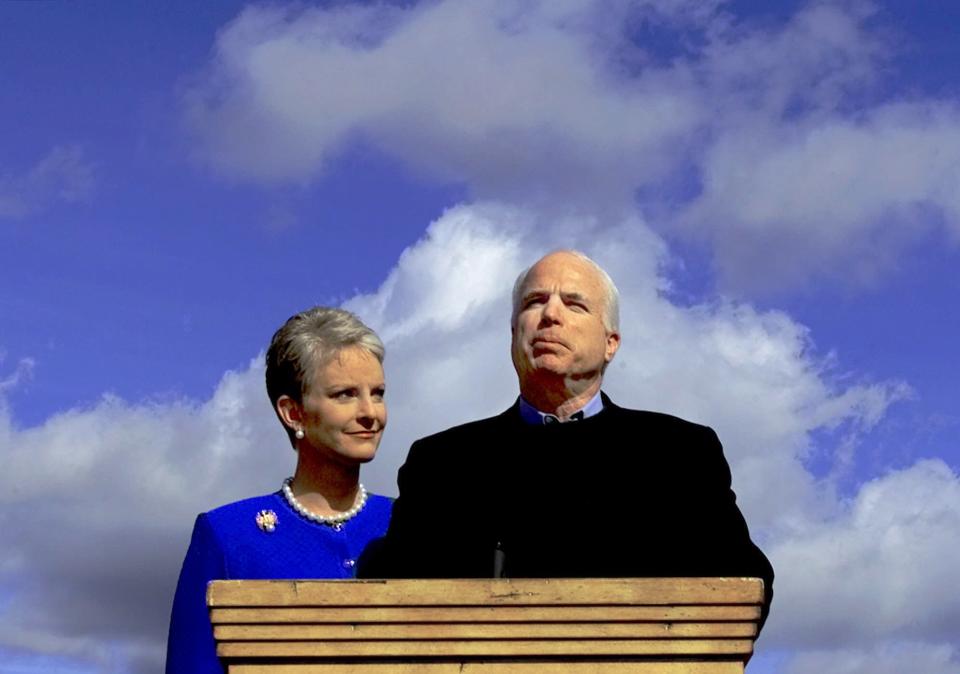

The following week, I watched him wake up from a nap in a Columbia, S.C., hotel suite to learn that fresh exit polls showed Bush crushing him in that state’s crucial primary. His hopes for the nomination were now in tatters. As I sat on the couch next to a weeping Cindy McCain, an aide informed him that he had even lost among veterans. “These people disgust me,” Cindy said, referring to the local Bush campaign operatives who had circulated despicable fliers depicting their daughter Bridget, adopted as a handicapped infant from Africa, as the offspring of McCain and a black woman. “That’s politics, honey,” her husband said softly, his legendary temper fully in check. Later, he focused not on that smear but on his own failure in South Carolina to speak out against the Confederate flag flying over the Capitol, which he considered one of the biggest regrets of his life.

As the 2000 campaign wound down, I was a dinner guest at his ranch near Sedona, Ariz., where he cooked for his neighbors. After he was tortured in prison, McCain could no longer lift his arms above his shoulders, so his sport of choice became grilling. I watched him jump between four Turbo grills preparing his specialty, spicy chicken. If he ever got to the White House, he said, he would replace the putting green with outdoor cooking equipment. The following year, I saw him at Candice Bergen’s house in Los Angeles reducing A-list celebrities to ingratiating fans, cementing his place as the liberals’ favorite Republican. Later they would often be disappointed when he didn’t vote like a Democrat.

Beyond the access and charm, McCain captured the media’s attention because he was saying something important in those years about the stranglehold that special interest money has on our political system. His experience on the griddle in the late 1980s as a member of the so-called Keating Five (McCain and four other senators with ties to con-man bank president Charles Keating) gave him the zeal of a convert. My most distinct memory of his pushing through the McCain-Feingold campaign finance reform in 2002 was his contempt for Mitch McConnell, his main adversary on the bill.

One of the things we loved about McCain was that he was often up in the grill of Senate colleagues he thought were acting dishonorably; some of the same ones now calling him a hero were then spreading rumors that he was mentally unbalanced. But he kicked up and sideways, not down. His loyal staff adored him, an important indicator of character in Washington or anywhere else.

In 2004, McCain almost agreed to go on the Democratic ticket with his friend and fellow Vietnam War veteran John Kerry. McCain and Kerry had teamed up in 1995 to give President Bill Clinton — who had ducked service in that war — the cover he needed to recognize Vietnam, a major diplomatic achievement for all three.

In election years, McCain sometimes trimmed his sails to tack against right wing primary challengers. But “country over party” was more than a slogan to him, and bonds across party lines — so rare nowadays — were among the main reasons he stayed in the Senate so long. Honor and friendship were the coins of his realm, especially when someone was in trouble. McCain spent long hours visiting former Democratic Rep. Mo Udall when he was bedridden with Parkinson’s disease and gave the eulogy for David Ifshin, a radical antiwar protester who delivered broadcasts from Hanoi attacking U.S. fliers like McCain as baby killers. He was, as Joe Biden said in December, the guy you would call from a street corner if you were ever in trouble.

In 2015, I was repeatedly asked why McCain didn’t respond when Trump — who dodged military service during the Vietnam War — said, “He’s not a war hero. He’s a ‘war hero’ because he was captured. I like people who weren’t captured.” The answer was that McCain, like most combat veterans, was uncomfortable being called a hero; for years, he preferred to say, “I was in the company of heroes.” Trump’s outrageous statement effectively neutralized him for months. Had McCain attacked him, it would have been seen as personal, which of course it was. So his shots in 2017 against Trump’s “half-baked, spurious nationalism” and “divisiveness” didn’t contain the president’s name.

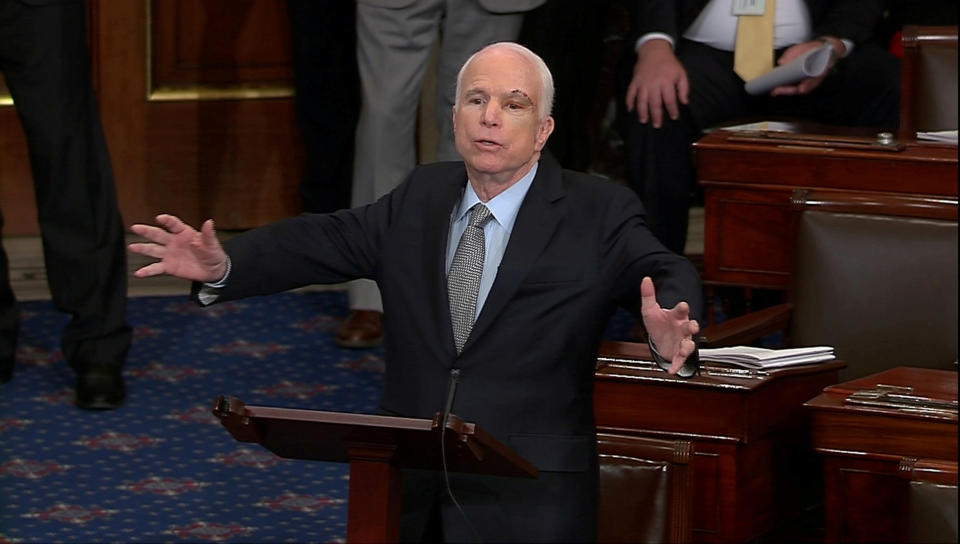

It was fitting that McCain cast the deciding vote against Trump’s repeal of the Affordable Care Act. The grounds he chose for voting no — that the traditions of the Senate had not been fully respected — reflected just how attached he was to the Constitution he had served in various capacities for more than 60 years. But the decency and character that so many reporters saw in McCain were perhaps best exemplified in October 2008 when as the Republican presidential nominee he faced a female questioner at a Minnesota town meeting who said of his Democratic opponent, Barack Obama: “He’s an Arab.” McCain didn’t hesitate: “No ma’am, he’s a decent family man, citizen, that I just happen to have disagreements with.”

That’s the John McCain I’ll remember.

(Cover thumbnail photo: Mary Altaffer/AP)

_____

Jonathan Alter covered John McCain on and off for two decades starting in the mid-1990s. He is at work on a biography of Jimmy Carter.

_____

Read more from Yahoo News: