Meet the Woman Behind Some of NASA's Most Famous Images

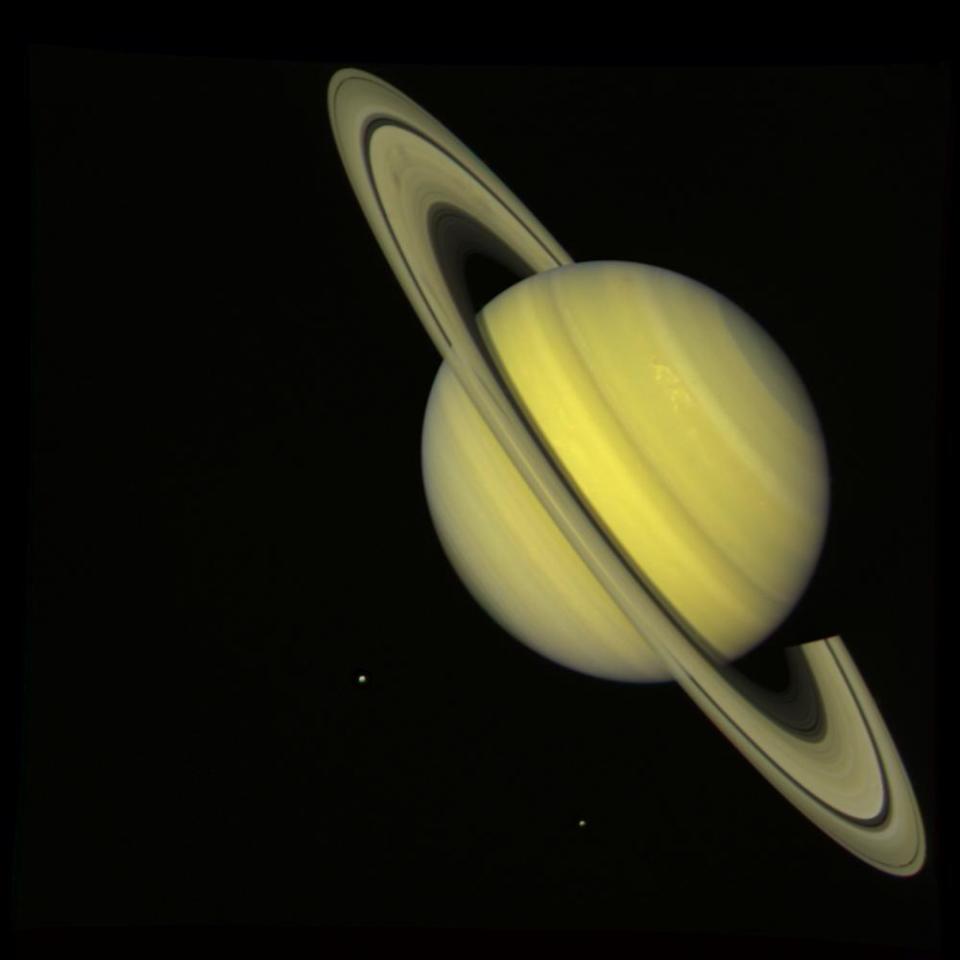

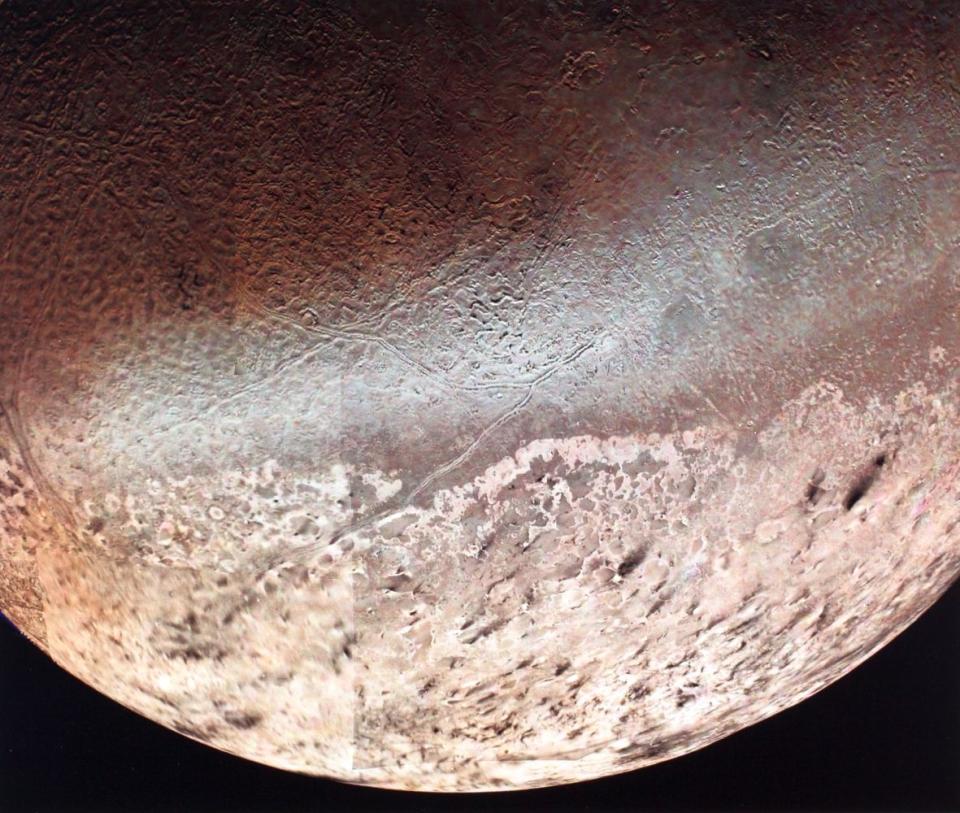

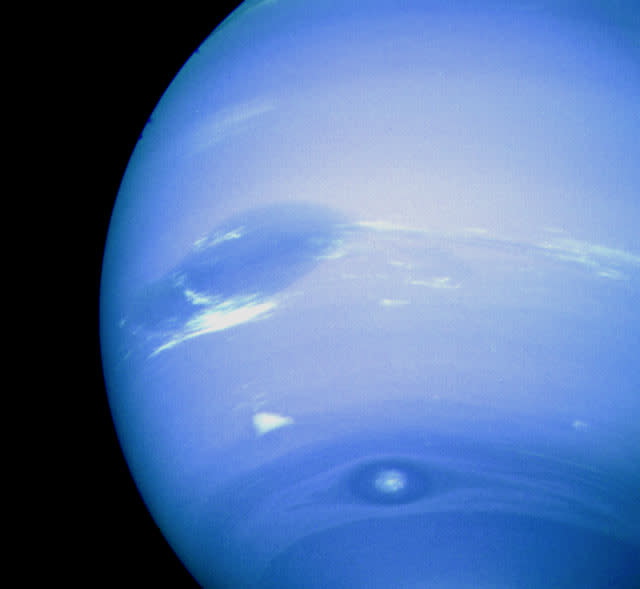

Humankind made its first major foray into interplanetary exploration in 1977, when NASA’s Voyager missions launched to study Jupiter, Saturn and their moons. As the years passed, however, the missions expanded, taking in Uranus and Neptune, and then continuing farther than any man-made objects have ever roamed.

Their journeys continue as they hit their 40th anniversaries: Voyager 2 was launched on Aug. 20, 1977, followed by Voyager 1 on Sept. 5; the confusing numbering was due to their different trajectories — Voyager 1 would be the first to get to its destinations.

And, while Voyager’s golden record retains its fascination and the scientific discoveries that came thanks to the mission are not to be underestimated, the general public is likely most familiar with the mission due to the images it has sent back to Earth. Many of those images are first-of-their-kind reminders of the beauty of space. One of the most famous, however, is the image seen above, which at first glance shows nothing much at all.

But more on that later.

The images provided by a mission like Voyager are more than pretty pictures, explains planetary scientist Carolyn Porco, imaging scientist for Voyager and imaging team leader for the Cassini mission at Saturn. (Porco is also featured in the documentary The Farthest: Voyager in Space, which premieres on PBS on Wednesday.)

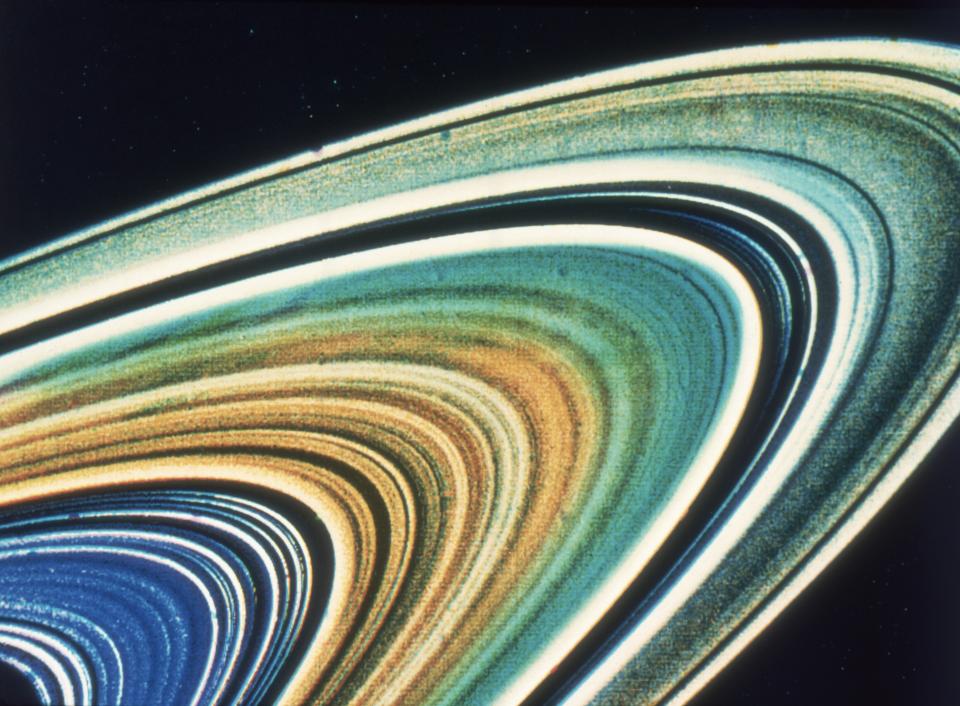

As Porco tells TIME, there are instruments that are carried on space-flight missions that can be used to detect light on one single spot, and thus collect information about what’s going on there. For example, if a star is watched while passing behind an atmosphere and it dims, scientists are able to use that detector to learn about what that atmosphere is made of and how it’s structured. The beautiful space images that the public loves so much are simply “a two-dimensional array of a million of those.” Even though the detectors Voyager scientists have at their disposal work with fewer megapixels than a modern cell-phone camera — they were launched in the 1970s, after all — that two-dimensional array is a powerful scientific tool. Each single point in the image is full of valuable data about the intensity of the signal.

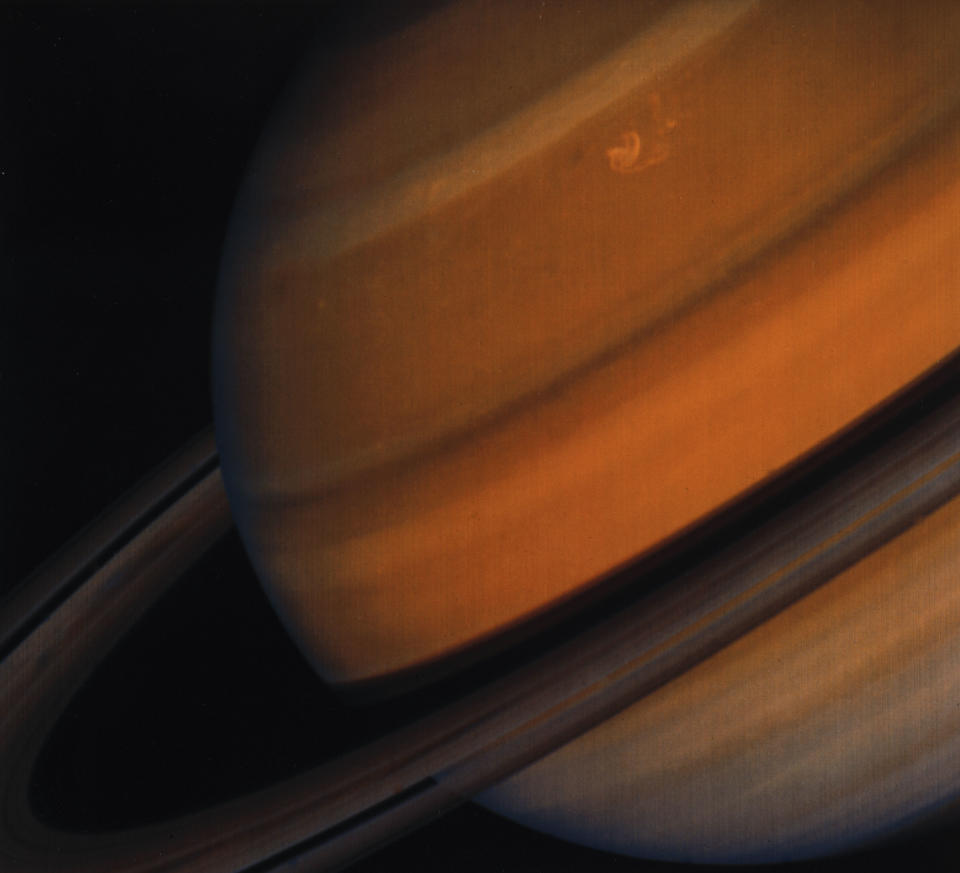

The beauty of those images is also a key scientific tool, in its own way. Porco compares these images to the 19th century paintings and photographs of the American West, which convinced those in power back East to invest energy and money into the exploration and preservation of lands they had never actually visited. Likewise, seeing what looks like a close-up photo of Saturn can convince us Earth-bound mortals to keep venturing out into the universe, if only vicariously.

“The reasons why images are so primal and people immediately relate to it is that we are exquisitely engineered to interpret information that is arrayed in two dimensions. That’s our eyesight,” she says. “That’s how our eye-brain system works. So it immediately feels to us when we look at an image like we have extended our senses. We have just immersed ourselves in that environment. That’s why people love images, because it transports them there.”

Though Porco says she carried that spirit into her work with Cassini, where she says she always goes out of her way to get the photo ops and make the public feel they’re “along for the ride,” one of the most famous examples of the power of an image from space remains that blurry black rectangle seen above — which was taken in 1990 by Voyager 1. The craft turned around to take a picture after completing its work near Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus and Neptune. On the orange-yellow band of light, a tiny bright dot can be seen.

That’s Earth.

Get your history fix in one place: sign up for the weekly TIME History newsletter

Porco says that she had the idea to have Voyager make an image of what the mission was leaving behind — Earth, that is — as soon as she started working on the project as an official member of the imaging team in October of 1983. However, as she spoke to colleagues about the idea, it got nowhere. Earth’s atmosphere didn’t need a distant image to be deciphered, and taking an extra step like that would endanger the mission for no particular scientific reason. After all, the light detectors on the Voyager crafts were not meant to capture the sun’s brightness, as they were built to face away from our planet and out into the cosmos. In order to take such a picture, the craft would need to be rotated so that the camera was shielded, but that would mean the antenna would no longer be facing Earth. And at that point, Porco says, it was very important to keep the communications antenna always facing home, as a dropped link might be lost forever.

A few years later — around 1988, she says — she learned that Carl Sagan had had the same idea and was also hitting a wall convincing NASA to take the picture. They teamed up (correspondence about which can now be found in the Library of Congress) and he convinced NASA the effort would be worth it.

“I did the technical stuff; my job was to figure out what the exposure times had to be. He did the political legwork,” she says. “In the proposal that he wrote to the Voyager project urging them to take this picture, he wrote that the point of it was to take a picture of the Earth ‘awash in a sea of stars.'”

When the image came back, however, there were no stars to be seen, and a beam of light obscured the Earth. “It wasn’t the most beautiful picture that you could possibly take, but it was Carl Sagan after all and it didn’t matter that the picture wasn’t very much. It was the way that he romanced it and turned it into an allegory on the human condition,” Porco says. He called the image “The Pale Blue Dot” and would later write in a book of that name: “There is perhaps no better a demonstration of the folly of human conceits than this distant image of our tiny world.”

Years later, after Sagan’s death, Porco was instrumental in orchestrating Cassini’s “The Day the Earth Smiled” photo, to “do the Pale Blue Dot over again, only make it the way Carl wanted.”

And even now, she says, when she sees images from space, the symbolism of those images comes first, and the hard science second.

“I’m not really an explorer and you’re not really an explorer but you and I can both look at a picture like that and we can feel like we are exploring our cosmic neighborhood,” Porco says. “It’s the significance in terms of the humanity and our development and evolution that strikes me first, and the beauty of it. After I’ve enjoyed that beautiful euphoria, then I roll up my sleeves and get my laptop out.”

Correction: The original version of this article misstated which Voyager took the Pale Blue Dot image. It was Voyager 1, not Voyager 2. It also misstated how the light of the sun might appear in an image of the Earth from the vantage point from which the Pale Blue Dot was taken. The sun could interfere with a photo of the Earth, but the planet would not be backlit.