McKee pushes state tax rewrite to keep Citizens Bank rooted in Rhode Island. But will it fly?

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

About 3,000 Citizens Bank employees work out of its 123-acre campus headquarters in Johnston. (Will Steinfeld/Rhode Island Current)

Citizens Bank’s Rhode Island roots run deep.

From modest beginnings as High Street Bank in Providence in 1828, to a history-making initial public offering in 2015, Rhode Island’s largest bank has fueled the Ocean State’s reputation and local economy for nearly two centuries.

Which is why a not-so-thinly-veiled threat that the locally headquartered financial powerhouse would pour its attention, and money, outside Rhode Island made hearts race on Smith Hill.

At least, for Gov. Dan McKee. In a May 10 budget memo, McKee proposed overhauling how the state taxes banks, offering the option to replace the longtime “three-factor” tax calculation based on in-state sales, property and payroll with a “single-factor” formula that only considers in-state sales.

The proposal comes a month after Mike Knipper, executive vice president and head of property and procurement for Citizens Financial Group Inc., wrote a letter to lawmakers warning the company “would strongly consider expanding its corporate footprint and employee base outside of Rhode Island because of differing tax treatment among the states.”

But should the state rewrite its tax regulations in an attempt to hold on to a company that has shifted its focus away from local retail branches to national acquisitions? Depends who you ask.

“This eliminates the disincentive which dissuades businesses from making investments in employees or physical presence in the state,” Joe Codega, state budget officer, told lawmakers at a House Committee on Finance hearing on Thursday, May 16. “Consider now, if a bank taxpayer makes an increase in the number of Rhode Island-based jobs and Rhode Island-based payroll relative to other states, they will end up having to apportion a greater percentage of total net income to Rhode Island taxes.”

Other states, including neighboring Massachusetts, are moving away from taxing companies’ in-state payroll and property. Knipper in his letter referenced the 2023 Bay State legislation, which removes property and payroll from tax calculations effective Jan. 1, 2025.

According to Knipper, the Commonwealth’s move to a single-factor tax calculation, based only on how much money a bank makes on loans, fees and interest on deposits, affects not just for Citizens, but “any large bank.”

Sen. Sam Bell, a Providence Democrat and vocal critic of state incentives for corporations, called Knipper’s warning an empty threat that amounted to extortion.

“This is a drastic and dramatic proposal that would blow up bank taxation in the state of Rhode Island,” Bell said in an interview Thursday.

Attempting to call Knipper’s bluff on the threat of moving jobs and offices out of state, Bell said it was unlikely the company would abandon its $285 million Johnston headquarters, which opened in 2018.

“They might move a couple additional office jobs to Massachusetts, at best,” Bell said.

Bell worried that rewriting state tax law to accommodate Citizens would “open the floodgates,” prompting other businesses to come knocking in search of their own tax changes and deals.

A serious threat? Or a bluff?

Nowhere in McKee’s budget memo is Citizens mentioned by name. However, Olivia DaRocha, a spokesperson for the governor’s office, confirmed in an email Friday that the proposal resulted from a request by Citizens Bank.

Rhode Island’s banking landscape is dotted with longstanding local companies like The Washington Trust Co. and Bank Rhode Island, alongside national and international heavyweights like Bank of America and Chase Bank. But Citizens is unique in that most of its money made off banking services comes from outside Rhode Island, yet its physical presence and payroll are weighted toward the Ocean State.

Under state law, only the portion of a bank’s sales, property and payroll within Rhode Island are taxed. Income made from services in other states is subject to those states’ taxation laws.

Citizens boasts over 100 branches and ATMs statewide — twice as many as its top competitor — with 4,200 state employees, about 3,000 of whom work out of its sprawling, 123-acre headquarters in Johnston, according to Knipper’s letter.

By contrast, Bank of America, which has the second-largest share of in-state deposits according to the Federal Deposit Insurance Corp., is headquartered in Charlotte, North Carolina, which means its property and payroll in Rhode Island is confined mostly to branches and financial centers.

Rhode Island-based banks like Washington Trust, meanwhile, have limited sales and physical presences outside state lines. Presumably, that means a switch to taxing only sales — excluding property and payroll — would offer little savings to the Westerly-based bank.

Citizens was the only bank to submit testimony regarding McKee’s proposal, although the Rhode Island Bankers Association also gave input to the governor’s office, DaRocha said.

Three days after McKee’s budget memo, on May 13, Citizens hired former House speaker William Murphy, to lobby on its behalf, with a $25,000 annual payment, according to the state lobby tracker. The company declined to comment when asked if Murphy was hired to advocate for the tax change.

This is a drastic and dramatic proposal that would blow up bank taxation in the state of Rhode Island.

– Sen. Sam Bell, a Providence Democrat

Rhode Island Current separately contacted Washington Trust, Bank Rhode Island and Bank Newport, the three largest in-state banks, all of which declined to comment.

Non-banking companies, specifically those registered as C-corporations, already enjoy reduced state tax bills from a switch to single-factor tax calculations as part of a sweeping set of tax changes approved by Rhode Island General Assembly in 2014 and that took effect Jan. 1, 2015.

Only one-third of states use a different tax formula for banks compared with other types of businesses, according to the Tax Foundation. And when it comes to interstate competition, business tax structure is just as important as the actual rate, Janelle Fritts, a Tax Foundation policy analyst wrote in a 2021 blog post.

“Such factors can exacerbate a bad tax code, improve a code that is already good, or help compensate for uncompetitive rates,” Fritts wrote.

The Rhode Island Public Expenditure Council (RIPEC), which has long been sounding the alarm on the need to improve the state’s business tax climate, backed McKee’s proposal in a letter to lawmakers.

“The situation is unfair to financial institutions and should be corrected so that multistate banks located in Rhode Island are treated the same as other Rhode Island multistate businesses and can compete on a level playing field with banks in other states,” Michael DiBiase, president and CEO of RIPEC, wrote in the letter.

The switch to single-factor taxation of banks comes at a cost – $15.6 million a year, according to calculations shared by the House Fiscal Office. But the alternative, of losing Citizens’ presence and tax payments entirely, would be even more costly — “catastrophic,” in the words of Laurie White, president of the Greater Providence Chamber of Commerce

“The implications are symbolic and also financial,” White said. “The value added of having large-scale employers cannot be underestimated.”

How much Citizens pays in state income taxes was not available; the Division of Taxation cannot share payment or other identifying information about individual taxpayers, Paul Grimaldi, division spokesperson, said in an email.

But the company’s contributions to Rhode Island go well beyond its annual tax bill: creating jobs, and in turn, workers who pay state income and property taxes, and vendors and small businesses whose operations depend on the financial giant’s local presence, DiBiase said in a separate interview Thursday.

“I think we need to do everything possible to keep headquartered companies like Citizens here,” he said.

Knipper in his letter argued that changing state tax calculations for banks won’t end up drastically reducing Citizens’ annual state tax bills. That’s primarily because the company can no longer qualify for a separate state tax credit program based on in-state jobs, as first reported by the Providence Journal.

Citizens has been the top benefactor of the controversial Rhode Island’s Jobs Development Act program since its inception in 1994. Indeed, the bank and its subsidiaries received nearly two-thirds of the $171.6 million in job-based tax credits offered to eligible companies from 2013 to 2022, according to a Rhode Island Department of Revenue report published in September. In fiscal 2023, Citizens Financial and its subsidiaries received about $21 million in tax credits through the program, according to a separate report by the state tax division.

I think we need to do everything possible to keep headquartered companies like Citizens here.

– Michael DiBiase, president and CEO of the Rhode Island Public Expenditure Council

But Citizens has stopped applying for the tax credit as of 2023 because it can no longer qualify, spokesperson Rory Sheehan confirmed in an email Friday. The incentive program requires employees work at least 30 hours in-state; post-pandemic, Citizens adopted a hybrid model in which workers, some of whom live out-of-state, report to the office three days per week.

Codega said during the Thursday hearing that Citizens’ new ineligibility for jobs tax credits translates to higher state revenue from bank taxes.

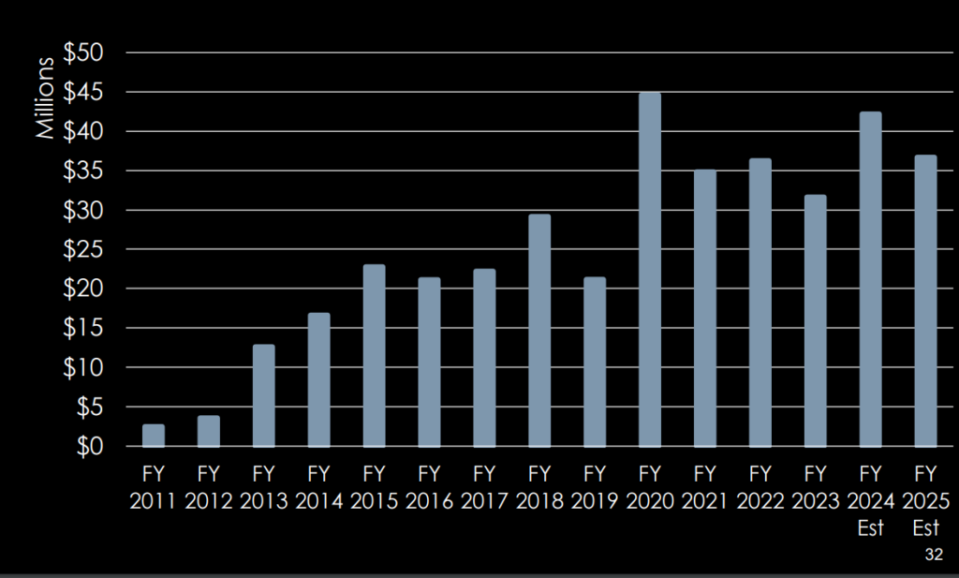

Under new revenue estimates adopted earlier this month, state budget crunchers now expect to bring in $42.2 million in bank tax revenue in fiscal 2024, which is $15.3 million more than previously forecast. Bank tax revenue will again beat expectations in fiscal 2025, up $10.3 million compared with prior projections.

The $15.3 million annual loss from a revised state tax calculation for banks would essentially offset the new, higher tax revenue estimates, Codega said.

The governor’s budget proposal also requires the Division of Taxation to gather data and issue a report to lawmakers by March 2027 showing how the tax change, if enacted, affects state revenue.

Neena Savage, state tax administrator, appeared during the May 16 State House hearing to answer questions from lawmakers, but did not take a position for or against McKee’s proposal.

‘Racing to the bottom’?

Rep. Teresa Tanzi, a South Kingstown Democrat, appeared unconvinced that returning excess revenue back to Citizens through a tax code rewrite was the best policy, especially given demands for more spending on housing, public transit and other high priority spending items in the state budget.

“It’s great to be able to accommodate and match Massachusetts from time to time, but I do have concerns,” Tanzi said. “I want to make sure we are not racing to the bottom.”

Rep. George Nardone, a Coventry Republican, questioned the “rush job,” referring to the eleventh hour nature of the governor’s proposal, six weeks away from the deadline to finalize a fiscal 2025 spending plan.

“It seems like this was put in the budget at the final hour,” Rep. George Nardone, a Coventry Republican, said. “Why did this all come about? Did something happen? Did the bank approach the governor? When you’re taking $7 million out of the budget at this final hour, it shows something is going on.”

Separately, McKee proposed spending $33.7 million to buy and renovate a former Citizens Bank loan office in East Providence for state administrative offices. Citizens still owns the Tripps Lane building valued at $16.9 million by the city of East Providence, which houses about 600 employees, according to Sheehan.

Both Sheehan and DaRocha said in separate emails that the building sale and tax change proposals, submitted two days apart, were unrelated.

Asked for a response to critics who question what seems like a new corporate handout, DaRocha said that the proposed tax change would be available to all eligible financial institutions, not just Citizens.

Two months before McKee’s budget memo, Rep. Joe Solomon, a Warwick Democrat, submitted legislation for a similar, though not identical, change to state bank tax calculations. Solomon did not respond to calls and emails for comment. His bill remains under review by the House FInance Committee following an April 11 hearing.

House Speaker K. Joseph Shekarchi and Senate President Dominick Ruggerio remained noncommittal when asked about McKee’s bank tax proposal.

“I want to keep an open mind,” Shekarchi said in an interview Thursday prior to the House Finance hearing on the proposal. “I need to hear the testimony for and against it.”

Greg Paré, a spokesperson for Ruggerio, said in an email that the Senate Finance Committee is expected to vet the proposal in a hearing this week.

“The Senate President has an open mind on the issue, which will ultimately be weighed in the context of the overall budget,” Paré said.

GET THE MORNING HEADLINES DELIVERED TO YOUR INBOX

The post McKee pushes state tax rewrite to keep Citizens Bank rooted in Rhode Island. But will it fly? appeared first on Rhode Island Current.