Martin Luther King Jr. didn't live long enough to see how we've dismantled his legacy

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

By 1968, Martin Luther King Jr. was flailing.

King hadn’t had a major victory in years, and his popularity had plummeted. As he neared death, almost 75% of Americans disapproved of him, labeling him a race-baiting troublemaker. Painfully for him, even a majority of Black people didn’t support him.

Those closest to King wondered how he could go on as he tumbled into depression.

The immediate past provided no encouragement in 1968. Medgar Evers had been shot to death on his driveway in Jackson, Mississippi, in June 1963. King’s simultaneous rival and comrade Malcolm X was murdered just over a year and a half later in New York.

The Black Power movement had been born a few years earlier, and its leaders were already targeted, persecuted and, at times, marked for death.

King’s 13 years on the front lines of America’s Civil Rights War ended when he was murdered in Memphis, Tennessee, on April 4, 1968. He was only 39 years old.

What followed his death was a string of events that served to dismantle his legacy and allow anti-Blackness in America to flourish.

Martin Luther King Jr. became another abandoned Black leader

Like W.E.B. Du Bois, Paul Robeson and others, King had been abandoned by many leaders of the NAACP and other Black legacy organizations.

He was still hounded by the U.S. government as FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover and COINTELPRO continued efforts to destroy Black leaders and resistance to racial inequality.

He was struggling to hold together his own coalition of lieutenants like Ralph Abernathy, Jesse Jackson, Andrew Young, Hosea Williams and others, who all quickly went their separate ways after King’s death.

What are states legislating against DEI afraid of? The truth about our racist history.

Du Bois, one of Black America’s greatest intellectuals, had given up seven years earlier. He wrote to his friend Grace Goens in September 1961: “I just cannot take any more of this country’s treatment. ... Chin up, and fight on, but realize that American Negroes can’t win.”

Du Bois left for Ghana the next month and never returned. He died the day before the 1963 March on Washington, a mere two months after Evers.

MLK did not live to see us misuse his words

King did not live to see racist anti-Black politicians and pundits misuse his words arguing people should “not be judged by the color of their skin but the content of their character” to oppose Black progress.

He did not live to see the Civil Rights Act of 1964, for which he fought for, so fiercely weaponized by the U.S. Supreme Court and attorneys general like Kentucky’s Russell Coleman to justify the legal destruction of affirmative action and diversity initiatives – setting the fight for racial equality back decades.

King did not live to see the Voting Rights Act of 1965, of which he was so proud, gutted and rendered little more than a “dead letter” by the Shelby County v. Holder ruling in 2013. Since then, racial voting disparities in America have increased exponentially.

Opinion alerts: Get columns from your favorite columnists + expert analysis on top issues, delivered straight to your device through the USA TODAY app. Don't have the app? Download it for free from your app store.

King was a brave man born out of the Black radical tradition

King did not live to see cowardly Black free-riders (not Freedom Riders) – who will not open their mouths in defense of their people – benefit from his sacrifice and suffering.

He did not live long enough to see the Ward Connerlys, Clarence Thomases, Candace Owens and Daniel Camerons of the world.

MLK was my friend. How can I be excited for the future when lessons from past are ignored?

He didn’t live to see Sen. Tim Scott, R-S.C., skinning, grinning and genuflecting before Donald Trump as he bastardized the words of Fannie Lou Hamer.

He did not live long enough to see a Black man running for governor of North Carolina proudly proclaim that Black people owe America reparations.

Nor did King live long enough to see a Black president or the unrelenting white backlash that has followed him.

What would King think of America today?

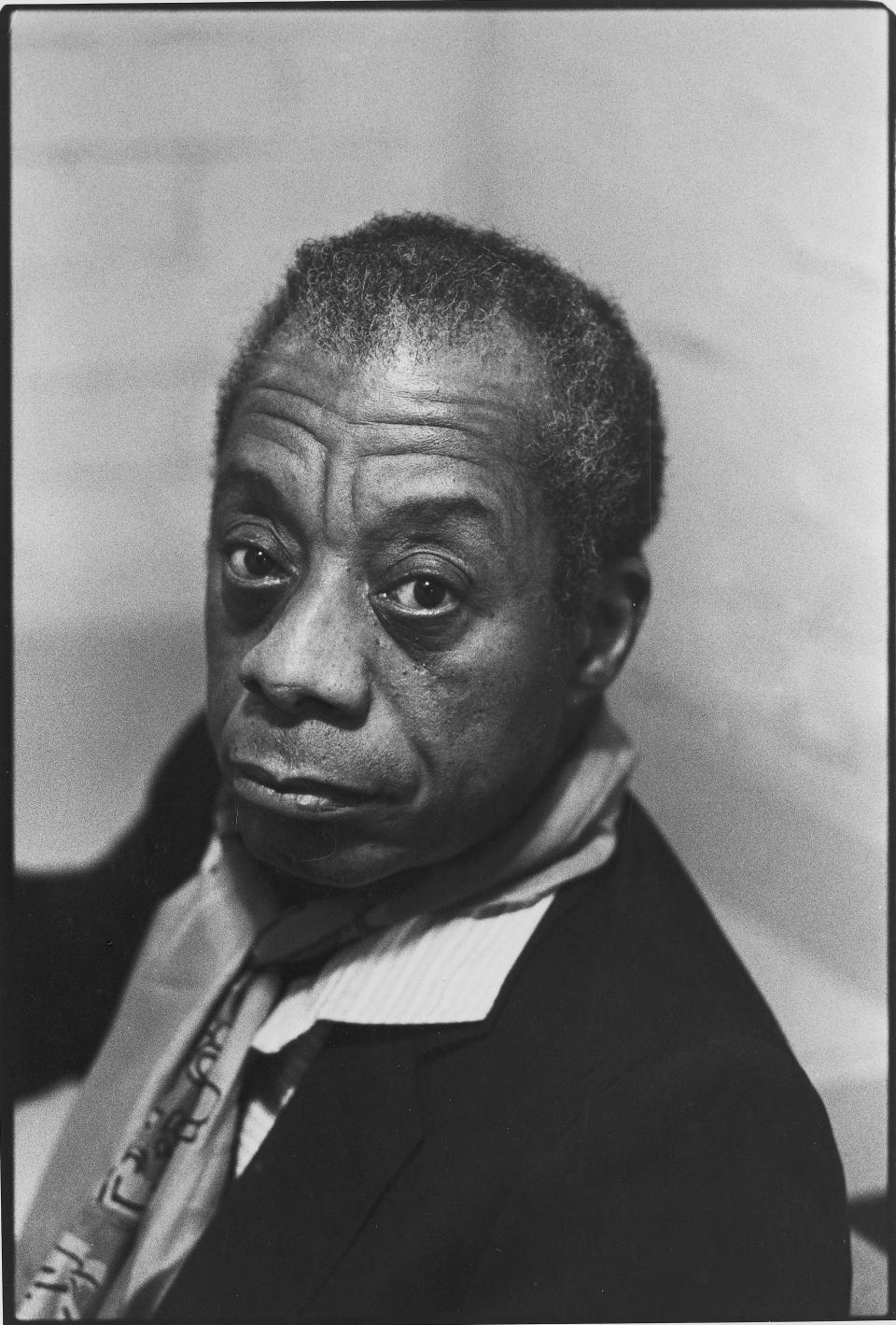

The searing truth-telling writer James Baldwin didn’t see most of it, either. He outlived King by two decades, eventually dying in 1987 during the racial onslaught of the Reagan era. He was only 63.

For those decades, Baldwin was the one left behind. He lived long enough to bear witness to the grief, pain and white retribution that followed his friends’ murders.

What Baldwin saw was neither pretty nor encouraging. He damningly reflects on America in Raoul Peck’s Oscar-nominated documentary, "I am not your Negro": “I’m terrified at the moral apathy – the death of the heart which is happening in my country. These people have deluded themselves for so long that they really don’t think I’m human. I base this on their conduct, not on what they say. And this means that they have become, in themselves, moral monsters.”

Current political and social anti-Blackness has grown more and more brazen in America and, unfortunately, there are no Kings or Baldwins left to fight it. What would Baldwin, King and their fellow warriors think of America today?

Ricky L. Jones, the Baldwin-King Scholar-in-Residence at the Christina Lee Brown Envirome Institute, is a professor of Pan-African Studies at the University of Louisville. His column appears biweekly in the Louisville Courier Journal, where this piece originally published.

You can read diverse opinions from our Board of Contributors and other writers on the Opinion front page, on Twitter @usatodayopinion and in our daily Opinion newsletter.

This article originally appeared on Louisville Courier Journal: MLK fought for a better America for Black people than we have today