Mars could be creating 'giant whirlpools' deep within our planet's oceans

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

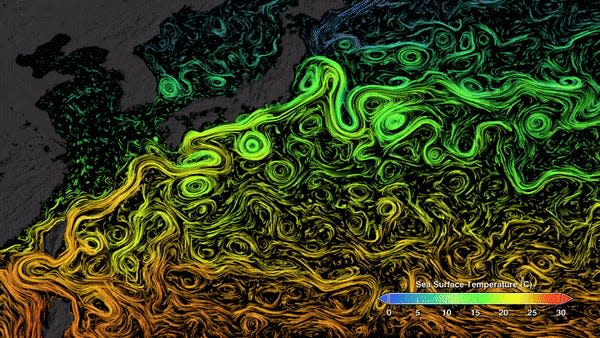

The gravitational pull Mars exerts on Earth may be strong enough to impact ocean currents.

A study suggests Mars can cause deep-sea currents to change over a 2.4 million-year cycle.

The study could help scientists create better climate models of Earth.

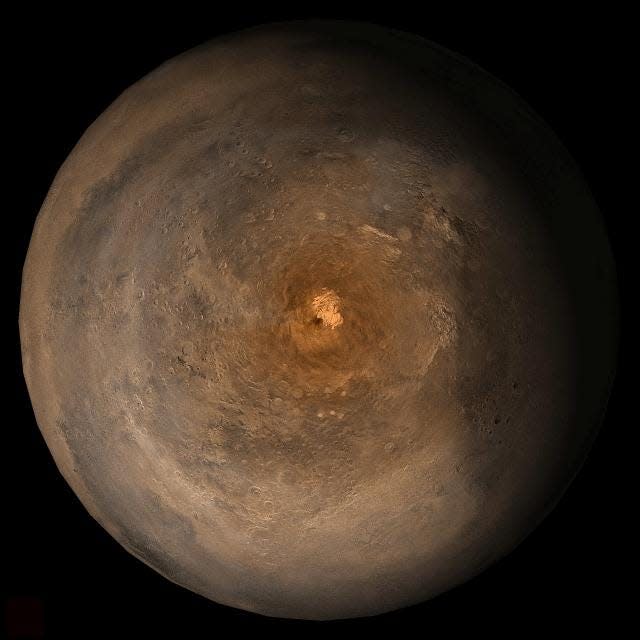

Mars may be 140 million miles away, but its gravitational pull could be impacting Earth's oceans.

Scientists at the University of Sydney in Australia believe the red planet's tug creates "giant whirlpools" in the oceans called "eddies," which can shift the deep-sea floor.

They claim this is part of a 2.4 million-year climate "grand cycle" on Earth that's been ongoing for at least 40 million years.

"We were surprised to find these 2.4 million-year cycles in our deep-sea sedimentary data," Adriana Dutkiewicz, a geosciences researcher at the University of Sydney, said.

"There is only one way to explain them: they are linked to cycles in the interactions of Mars and Earth orbiting the sun."

Tiny changes can have huge effects

If the climate crisis has taught us one thing, it's that seemingly insignificant events — such as humans using carbon-based fuels to power industries — can unleash catastrophic impacts on our delicately balanced climate down the line.

Scientists know human activity has contributed to rising global temperatures, but they're increasingly trying to figure out how other changes to the planet, such as its position in the solar system, could influence long-term climate trends.

Previous studies have suggested that tiny wobbles of the Earth on its axis could affect for the climate over tens of thousands of years.

Now, scientists are proposing an "astronomical grand cycle" on the scale of millions of years, which they say could be caused by the subtle effect of Mars's gravitational pull.

"Mars's impact on Earth's climate is akin to a butterfly effect," Dietmar Müller, an author of the study and a professor of geosciences at the University of Sydney, told New Scientist.

Earth resonates with Mars, and that slowly shifts the climate and oceans

The evidence for this theory lies in almost 300 deep-sea cores tracking ocean sediments back more than 65 million years.

These revealed that sediment deposits follow a very long cycle, ebbing and flowing every 2.4 million years.

This suggests something weird is happening on that time scale, which lines up suspiciously with periods of a warmer climate, Müller, Dutkiewicz, and their coauthor, Slah Boulila, said in a study published Tuesday in the peer-reviewed journal Nature Communications.

For the scientists, there's one culprit: Mars.

The red planet's orbit and Earth's are locked in an intricate dance, and every so often, these line up so that Mars' gravitational pull on Earth is just a little more intense — this phenomenon is called resonance.

This, in turn, could pull Earth ever so slightly toward the sun, increasing Earth's surface temperature and solar-radiation concentration.

That can have a domino effect on the climate through the seas. Oceans can create giant whirlpools ahead of warming climates.

This effect likely wouldn't upheave the climate on its own, but it could nudge our planet toward a slightly warmer system by tweaking the Atlantic current that regulates the Gulf Stream.

More evidence is needed

Not everybody agrees that the case is closed on these million-year variations.

Matthew England, from the University of New South Wales in Sydney, told New Scientist he was "skeptical" given Mars's weak gravitational pull.

"Even Jupiter has a stronger gravitational field for Earth," he said.

But if it's correct, this theory could add precious understanding to these "megacycles." This information is crucial when refining models helping us see how our planet's intricate climate could evolve.

"Many of us have seen these multi-million-year cycles in various different geological, geochemical and biological records — including during the famous explosion of animal life in the Cambrian Period," Benjamin Mills, a biogeochemist at the University of Leeds who wasn't involved in the study, told New Scientist.

"This paper helps cement these ideas as key parts of environmental change," Mills said.

Read the original article on Business Insider