Machines at the Bottom of the Ocean Witnessed the Recent Solar Storm

Compasses at the bottom of the ocean wobbled as a massive solar storm hit Earth last week, giving the instruments two miles under the sea a jolt of magnetic shock and awe.

The compasses are managed by Ocean Networks Canada, a national ocean observatory hosted by the University of Victoria. According to Alex Slonimer, a scientific data specialist at the observatory, a daily check in late March—over a month before the recent storm—turned up an anomaly in the reading.

“I looked into whether it was potentially an earthquake, but that didn’t make a lot of sense because the changes in the data were lasting for too long and concurrently at different locations,” Slonimer said in a University of Victoria release. “Then, I looked into whether it was a solar flare as the sun has been active recently.”

That was the first anomaly, but the real drama only occurred last week, when a significant solar storm arrived on Earth, causing some issues in the American power grid and—perhaps more excitingly—auroras across the globe. The auroraes were farther flung than normal; in the United States, auroras were spotted as far south as Florida.

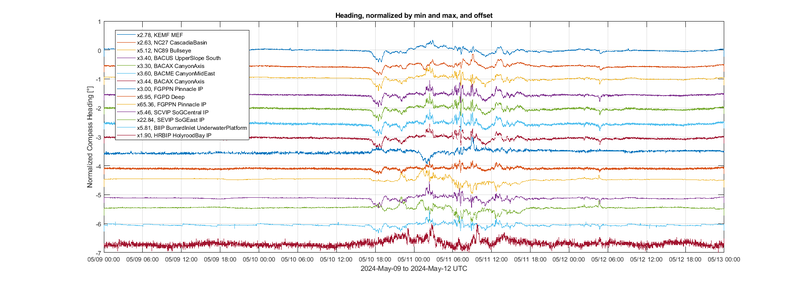

As seen in the graphic above, compasses across Ocean Networks Canada’s infrastructure wobbled as the geomagnetic storm hit the planet. The data shown above came from two of the network’s observatories off Vancouver Island, VENUS and NEPTUNE, and in Conception Bay on the Atlantic coast. The most sizeable magnetic shift occurred 82 feet (25 meters) beneath the ocean’s surface off Vancouver Island, where one heading shifted in a range of +30 to -30 degrees.

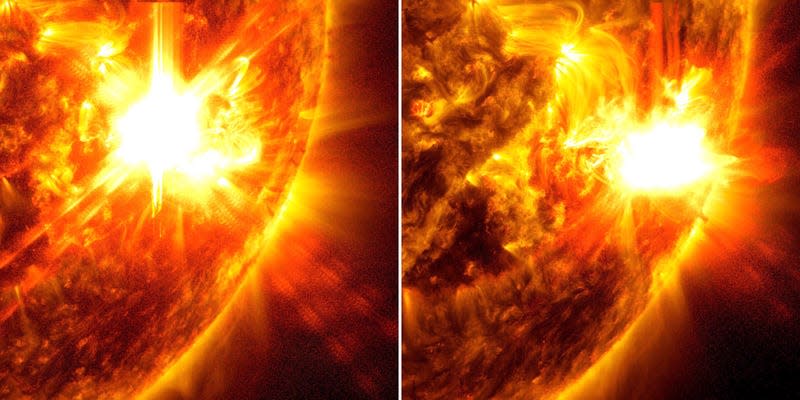

The ongoing activity on the Sun is the result of our host star’s 11-year solar cycle, which causes its magnetic field to flip back and forth. During the middle of the cycle, solar activity on its surface— solar flares and coronal mass ejections—tend to peak, sending voluminous solar material towards the Earth if the event is facing the right way.

Scientists with NOAA’s Space Weather Prediction Center issued a severe warning for the storm that hit last week, which was associated with several solar flares that occurred around a sunspot on the star 16 times as wide as Earth. The solar storm was categorized as an extreme, or “G5" event; the last G5 storm to hit Earth occurred 2003. As Gizmodo reported last week, the storm caused radio blackouts across Asia and in parts of Africa and Europe, and caused some irregularities in the American power grid.

“After a decade of relative inactivity, aurora events like this past weekend are likely to become more frequent over the next couple of years, although solar variability makes precise prediction of such events impossible,” said Justin Albert, a physicist at the University of Victoria, in the same release. “ONC’s network might provide a very helpful additional window into the effects of solar activity on the Earth’s terrestrial magnetism.”

Indeed, it’s easy to think about Earth’s magnetic field when looking up at a beautiful aurora. It’s another to remember that the magnetic field is not just active in the stratosphere, but in some of the deepest recesses of the planet.