Lula Plans Airline Bailout to Make Flying Cheaper for Brazilians

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

(Bloomberg) -- Brazil is putting the finishing touches on a rescue plan for its troubled airlines, as President Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva’s government confronts a challenge the US and Europe dealt with much sooner after the pandemic.

Most Read from Bloomberg

Stock Traders Bracing for Worst Shrug Off Hot CPI: Markets Wrap

Ex-Wall Street Banker Takes On AOC in New York Democratic Primary

US Core Inflation Tops Forecasts Again, Reinforcing Fed Caution

The package, to be announced in coming days, will use public funds as collateral for loans to struggling carriers from the country’s development bank, according to a person familiar with the matter. But the plan is still in flux and it’s expected to be more of a band-aid solution than an industry cure-all.

Cutting fares enough to allow the poor to fly regularly has become somewhat of an obsession for Lula, who campaigned on a pledge to restore prosperity in Latin America’s largest economy. The high cost of jet fuel in Brazil is a complicating factor, with the state-run oil company under pressure to overhaul its pricing formula.

Inaction by Lula’s predecessor after Covid-19 pushed domestic carriers to the brink. The new administration has been struggling to agree on a way forward, and when Gol Linhas Aereas Inteligentes SA filed for bankruptcy protection at the end of January the issue vaulted to the top the agenda. Azul SA is now exploring a potential takeover bid for its troubled competitor.

The exact amount of aid is still being determined. Some within government are pushing for as much as 8 billion reais ($1.6 billion), while the Finance Ministry prefers an amount closer to 5 billion reais, according to two people familiar, who spoke on condition of anonymity because the discussions are private.

“Airline companies didn’t receive government help during the pandemic and at some point you have to pay the price,” Ygor Araujo, an analyst at Genial Investimentos, said in an interview. By his estimation, a bailout of the size under consideration could relieve cash-flow pressures for six to eight months but wouldn’t be sufficient to lower fares on its own.

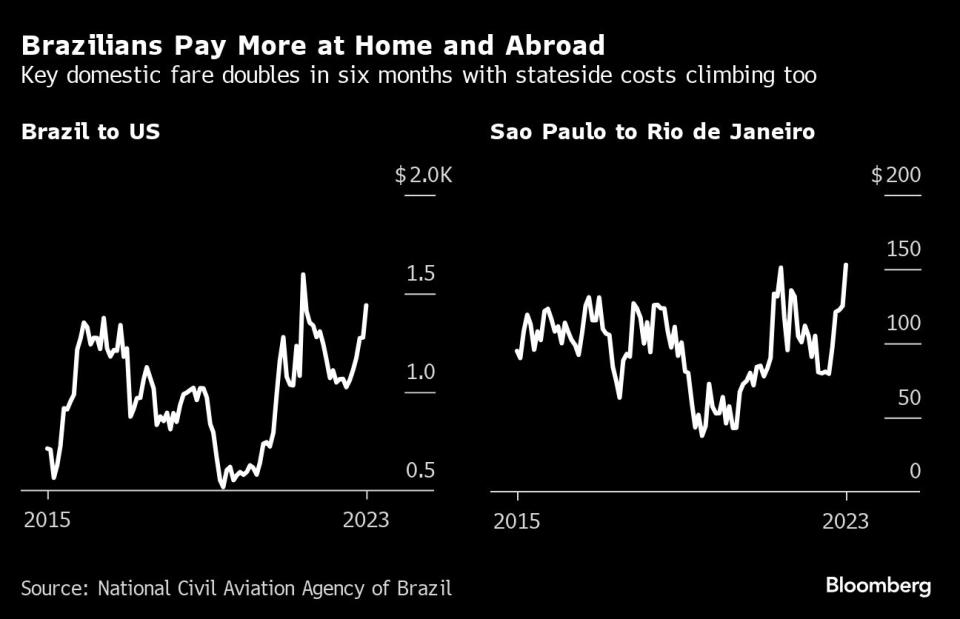

In addition to high fuel costs, Brazilian airlines are facing production delays on new aircraft, legal uncertainty and an extremely high number of lawsuits by unhappy customers. They have jacked up prices to make up for rising costs, with fares jumping nearly 50% in December from the year before.

The president has been particularly vocal about his dissatisfaction with the situation. “There is no explanation for the price of plane tickets in this country,” Lula said at an event in Amapa state that month, adding that some tickets to the northern region cost as much as 10,000 reais.

Many in the working class are taking him at his word and awaiting results. Dulce da Conceição, a housekeeper for over 35 years in Brasilia, is looking forward to lower airfares so she can visit her family in the country’s northeast more frequently. “It would be much better to go by plane than by bus,” she said in an interview.

Airlines have been getting an earful over the issue. At an industry forum in Sao Paulo last week, Azul Chief Executive Officer John Peter Rodgerson said companies faced weekly scoldings from the government throughout 2023 as fares climbed. His counterparts at Latam Airlines Group SA and Gol conceded at the same event that high prices are hindering access to travel.

But merely backstopping loans from BNDES, the development bank, likely won’t be enough to bring consumer prices down. “The BNDES line does not resolve the issue as it would not be used to subsidize tickets but rather help with companies’ liquidity issues,” said Carolina Chimenti, a credit analyst at Moody’s Investors Service, who flagged exchange rates and fuel costs as other key issues.

Despite its Chapter 11 process, Gol maintains it’s still eligible for the BNDES credit line, according to a person familiar with the matter. The airline didn’t reply to a request for comment.

Latam confirmed that it’s in talks with the government about ways to bring down fares, saying in an emailed statement it sees increasing the supply of seats and reducing structural costs as key requirements.

And Azul believes the sector isn’t growing as fast as it should in Brazil, citing Rodgerson’s comments in a recent Bloomberg interview. The CEO said at the time that a domestic credit line could mitigate exchange-rate fluctuations and ultimately help boost capacity.

Lula’s government is considering other measures to lower ticket prices. One new program under discussion, known as Voa Brasil, is aimed at persuading airlines to offer discounted fares to students and retired workers.

On fuel costs, the government is urging Petroleo Brasileiro SA to change its pricing procedures but has so far met stiff resistance. Although Brazil produces almost all of the jet fuel used in the country, the state-run company calculates prices as if it were imported, which brings currency volatility to the equation.

Industry executives see lowering fuel prices as a longer-term process. But that could change if Lula decides to intervene directly in the company’s affairs, as he is said to have done last week in orchestrating the Petrobras board’s rejection of a dividend proposal. The move erased $11 billion of the state-run firm’s market value in a day.

Another challenge is sky-high litigation rates that cost companies millions each year.

Brazilian airlines face between 8,000 to 10,000 lawsuits each month. The combination of a strong consumer protection code, which applies to air carriers, and an accessible legal system mean that unsatisfied customers in Brazil are 800 times more likely to head to court than those in the US.

Competition is also an issue. Brazil’s aviation regulator, known as ANAC, said that of eight new airlines licensed to operate in the country since 2019, two ultimately stopped flying and another never got started.

“A firm reduction in fares will be achieved with an increase in the supply of seats — a tremendous challenge around the world after the pandemic” said José Roberto Afonso, an economist and researcher at the University of Lisbon who also teaches at IDP in Brasilia.

The International Air Transport Association agrees there’s no silver bullet for Lula’s government.

“Brazil needs to effectively resolve its structural problems such as the high cost of aviation fuel, especially when compared to the main markets, prohibitive cost of capital and excessive judicialization that act as significant obstacles to the sector’s enormous growth potential,” the global airline industry group said in response to written questions.

--With assistance from Giovanna Serafim, Beatriz Reis, Leda Alvim and Gabriel Tavares.

Most Read from Bloomberg Businessweek

Gold-Medalist Coders Build an AI That Can Do Their Job for Them

Academics Question ESG Studies That Helped Fuel Investing Boom

Luxury Postnatal Retreats Draw Affluent Parents Around the US

Primaries Show Candidates Can Win on TikTok But Lose at the Polls

How Apple Sank About $1 Billion a Year Into a Car It Never Built

©2024 Bloomberg L.P.