Lucy, our early human ancestor, may have died after falling from a tree

Lucy, a famous early human ancestor that lived about 3.2 million years ago, may have died after falling from a tree, her bones and organs smashing into the savannah of present-day Ethiopia, a new study suggests.

Lucy's fatal fall is likely the first scientific hypothesis pointing to how the ape-like hominid died, according to the research published Monday in the journal Nature.

U.S. researchers found Lucy's remains in 1974 but, until recently, body-scanning technologies could glean only a few foggy clues from the ancient skeleton.

SEE ALSO: A 66-million-year-old T. rex is about to fly from Chicago to Amsterdam

"People die for lots of different reasons, but most of the reasons are not recorded in the bones," John Kappelman, the study's lead author and a geological sciences professor at the University of Texas at Austin, told Mashable.

"It's rarely the case that fossil bones record evidence of how the individual died," he said in a phone interview.

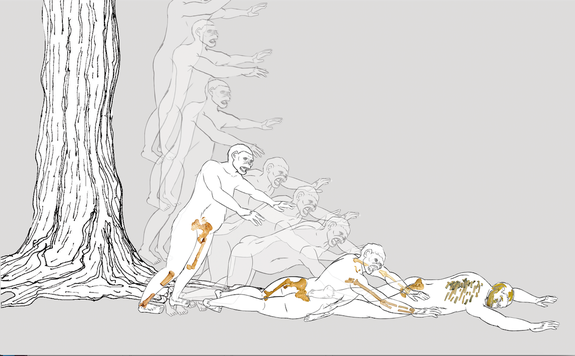

Image: university of texas, austin

The study adds to the contentious debate about whether or not Lucy and her Australopithecus afarensis species — which walked upright — lived in and moved easily through trees.

While Kappelman and his colleagues said they may have found new answers about Lucy's death, other Lucy experts said the ambiguous nature of fossils makes it difficult to know what actually happened to her bones over the course of millions of years.

"There are many different forces that act to destroy and deform bones that enter the fossil records, and trauma is only one of them," said William Kimbel, director of the Institute of Human Origins at Arizona State University, in an interview.

Kimbel was a junior author on a 1982 article about Lucy by Donald Johanson, who discovered her bones in Ethiopia's northern Afar region.

Scanning Lucy

The UT-Austin researchers said they determined Lucy likely plunged to her death after studying a specific set of fractures in the fossilized bones.

Kappelman and another geological sciences professor, Richard Ketcham, scanned Lucy's skeleton using UT-Austin's high-energy, high-resolution computed tomography (CT) facility, an advanced version of the X-ray equipment used in modern medical settings.

Image: ullstein bild via Getty Images

The device can scan through materials as solid as a rock and reveal structures as thin as a human hair. It is also significantly more powerful than the CT machines scientists used to scan Lucy's remains in the 1970s and 1980s.

Kappelman said he jumped at the chance to run Lucy through the powerful scanning technology in 2008, when the Ethiopian government was exhibiting the fossil at museums in Houston and across the United States.

After 10 days of scanning, the results revealed a series of compressive fractures that were likely caused when one bone jammed into another, a sign of extreme trauma.

Lucy's right proximal humerus — the upper arm bone — was severely shattered, suggesting she instinctively stuck out her arm in an attempt to break the fall.

Researchers observed similar but less severe fractures at the left shoulder and other compressive fractures in the right ankle, left knee and pelvis and even the top rib bone, which is difficult to break except in traumatic injuries.

In living bodies, bones will gradually attempt to heal themselves, smoothing the sharp edges of clean breaks and sealing tiny slivers. But Lucy's skeleton showed no signs of healing, suggesting the fractures happened near the time of death, according to the study.

Kappelman and Ketcham used the CT scans to create a modern, human-scale 3D printed model of Lucy's skeleton. They presented the model to Dr. Stephen Pearce, an orthopedic surgeon at the Austin Bone and Joint Clinic.

"I didn't tell him what it was, I just said I had an old fossil to look at," Kappelman recalled. "He said, 'That's a four-part proximal humerus fracture.' No questions, no hesitation."

Researchers showed the model to other surgeons in Austin and Seattle, who unanimously agreed that, because the fractures were so severe and Lucy's bones were otherwise healthy, the injuries were caused by a high-energy traumatic event.

"It's probably a combination of the fractured skeleton and internal organ damage that actually killed her," Kappelman said.

Image: University of texas, austin

The professor, who has studied Lucy for 30 years, said that discovery was a surprisingly emotional experience.

"Those breaks in her shoulders very strongly suggest she was still alive at that moment as she moved her arms up and tried to break the fall," he said.

"This box of bones all of a sudden had life breathed into them."

Study under scrutiny

Kimbel, the director of the Institute of Human Origins at Arizona State University, said that by presenting Lucy's fractures in a modern-day clinical setting, the UT-Austin researchers excluded other possible reasons for the cracks in the ancient bones.

"They didn't evaluate all the potential sources of damage to Lucy in a systemic way," he told Mashable. "Until that's done, this is not a well-supported explanation. It's just a story."

Kimbel said he has observed similar bone fractures in the fossils of other animals that likely never dwelled in trees — including antelopes, hippopotami and horses — meaning the bones sustained similar damage in other ways, whether by degrading on the surface, eroding once buried in the sediment, or breaking up as they emerged on the surface a second time.

"The clinical comparison gives you only a single plausible explanation for damage, and that's trauma," he said in an interview. "You can't apply the clinical parallel to [Ethiopia's] Rift Valley setting 3 million years ago."

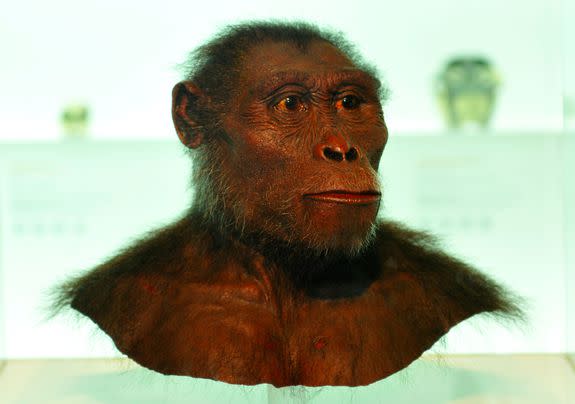

Image: De Agostini/Getty Images

On the Institute of Human Origin's website, Kimbel explains that the only clear damage seen on Lucy's bones is a single tooth puncture mark on her left pubic bone, likely from a meat-eating predator. The bite may have happened after she died but while the bone was still fresh, and if that's the case, it likely wasn't related to her death.

"No cause has been determined for Lucy’s death," the website says.

The vast majority of fractures seen in Lucy's skeleton likely happened after she died, according to the 1982 article describing Lucy's anatomy that Kimbel helped produce. Most of those fractures are probably due to common geological processes that damage and degrade bones over time, the researchers found.

Kappelman, responding to Kimbel's critiques, said he and his research team are in "nearly complete agreement" with the 1982 paper's conclusions.

"We differ, though, in suggesting that not all of the fractures in Lucy's skeleton are the same," he said, referring to the subset of compressive fractures they closely studied.

Kappelman said the researchers studied Lucy's fractures in a modern-day clinical setting because they felt the damage was "very unlikely" to have been produced by geological processes.

"The clinical record fully documents both perimorterm [time of death] and antemortem [before death] fractures in a way that the fossil record does not," he added. "This is why we use the clinical data, and we believe that these data should be used to their fullest extent."