Lost Alan Turing letters found in university filing cabinet

The documents include a letter from GCHQ and a draft BBC radio programme.

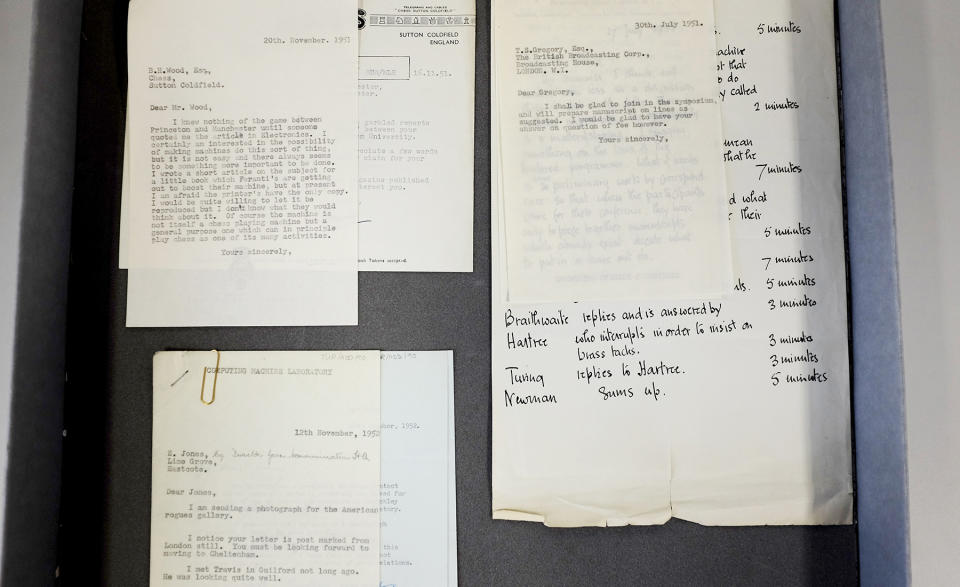

A huge batch of letters penned by British cryptographer Alan Turing has been found at the University of Manchester. Professor Jim Miles was tidying a storeroom when he discovered the correspondence in an old filing cabinet. At first he assumed the orange folder, which had Turing's name on the front, had been emptied and re-used by another member of staff. But a closer look revealed 148 documents, including a letter sent by GCHQ, a draft version of a BBC radio programme about artificial intelligence, and invitations to lecture at some top universities in America.

Turing worked at the University of Manchester from 1948, first as a Reader in the mathematics department and later as the Deputy Director of the Computing Laboratory. These jobs followed his pivotal work with the Government Code and Cypher School during the Second World War. At Bletchley Park, he spearheaded a team of cryptographers that helped the Allies to unravel various Nazi messages, including those protected by the Enigma code. The newly discovered documents date from early 1949 until his death in June 1954. At this time, Turing's work on Enigma was still a secret, which is why it's rarely mentioned in the correspondence.

None of the letters contain pivotal or previously unknown information about Turing. They do provide detail, however, about his life at Manchester and how he worked at the university. They also shed light on his personality — responding to a conference invitation in the US, he said: "I would not like the journey, and I detest America." The documents also reference his work on morphogenesis -- the study of biological life and why it takes a particular form -- computing and mathematics. "I was astonished such a thing had remained hidden out of sight for so long," Miles said.

All of the letters have now been sorted and stored by archivist James Peters at the university's library. "This is a truly unique find," Peters said. "Archive material relating to Turing is extremely scarce, so having some of his academic correspondence is a welcome and important addition to our collection." You can now search for and view all 148 documents online.

None of the correspondence references his personal life. Turing was arrested in 1952 for homosexual acts and chose chemical castration over time in prison. In 1954, he died through cyanide poisoning, which an inquest later determined as suicide. The British government officially apologised for his treatment in 2009, before a posthumous pardon was granted in 2013. Last October, the UK government introduced the "Alan Turing Law," awarding posthumous pardons to thousands of gay and bisexual men previously convicted for consensual same-sex relationships.