They lost by 103. But coach is on a mission to fight for this rural NC basketball team

This story is part of “The Lost Year,” an occasional series on how the pandemic is affecting education across North Carolina.

He looked at the scoreboard and wondered how much more his players could take. They were teenagers, mostly 15 or 16, and throughout their lives in Warren County, one of the most rural and poorest in North Carolina, they’d grown used to loss without knowing it.

That was part of why Toriano McRae Jr. worked where teachers couldn’t wait to quit. To help stop the losing. To help forgotten kids in a forgotten place learn they could depend on someone to stay. He was in his second year as the boys basketball coach at Warren County High, and during his worst loss yet he wondered whether it was time to give in.

For 10 months during this pandemic, high school kids in Warren County had lost what their peers had lost everywhere: Time with friends and in classrooms. School dances and carefree afternoons.

Students lost purpose. Some lost the comfort of a reliable meal or the will to sit through online classes. Others went without internet access to attend those classes in the first place.

Now, on a mid-January night in a mostly empty gym in Creedmoor, the Warren County Eagles were suffering through a loss of a different kind, one that personified all the others. At the end of the first quarter, they were losing a game by 41 points.

At halftime, the margin was 70: South Granville High with an 82-12 lead.

In the locker room during intermission, McRae tried to find the words. At 26, he was not much older than his players, and he often lamented the bad habits that came with losing. He spoke of fighting and pride and everything coaches say when their teams look lost.

There was nothing in the manual about coaching through a 70-point deficit.

At the start of the fourth quarter, his team now down by 85, McRae looked at an assistant and said, “They’re trying to beat us by 100.” One of his players, a sophomore named Rocky Carter, said he heard one of the South Granville players say its coach was “trying to set a record.”

After, Carter searched on his phone. The final score was South Granville 117, Warren County 14. He and his teammates had lost by 103 points. He found the state record book and stopped where it said, in capital letters: LARGEST MARGIN OF VICTORY. He stared at the score the next line down:

Haw River 142, Elon 40. A margin of 102 points. A record that had stood since 1954.

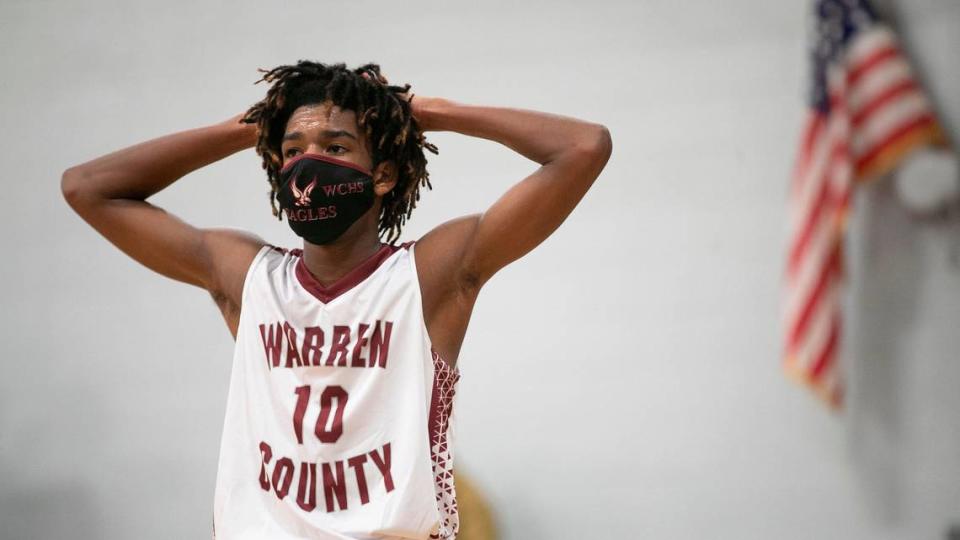

Moments earlier, the end had brought a release. Carter and some of his teammates cried. Now he sat on the bus in silence with the realization he’d been on the other side of the most one-sided boys basketball game in North Carolina history. Hundreds of thousands of games, spanning decades, and never a final margin as great as this one.

Carter tried to comprehend the number. He was a skinny 5-foot-11 with a big mane of shaggy long hair and bigger dreams that fueled his straight-A GPA. He’d never imagined losing a game by 30 or even 50 points. But 103?

“I always like to be the best at what I do,” he said. “It can be school, it can be anything.”

Now he and his teammates felt like the biggest losers in state history. The bus rolled north into the quiet dark of the country, Carter and his teammates together but alone with their doubts. McRae stopped at a McDonald’s off the highway in Oxford, halfway home, hoping it might break the silence.

“It’s a long bus ride home,” he said later. “I knew they were hungry. We just lost by 100. I just felt like food — food can sometimes be a good coping mechanism.”

His players ordered burgers and nuggets and slowly began talking again. Some of them asked McRae if it might be OK if he didn’t post the score online. They didn’t want anyone to know.

**

Warren County is an hour north of Raleigh along U.S. 401, the urban sprawl growing more distant in the rearview mirror. After a while, the land turns wide open and the road narrows, two lanes surrounded by Dollar Generals and small brick churches. Old wooden barns and houses collapse into the countryside, the occasional crumbling chimney poking through the rubble.

The road passes into Warren County and through Afton, where in the early 1980s protests of a toxic waste site ignited a years-long environmental justice movement. The road winds through Warrenton, the county seat, where antebellum homes line tree-canopied streets, and where for weeks in 1970, two years after integration, Black high school students in this predominantly Black county marched down Main Street in protest of inequality.

More than 50 years have passed and now, like then, the road stretches into the vastness of the country near the Virginia line. This is a place where dreams vanish into the monotony, where young people hope these country roads lead them somewhere else.

McRae instead followed those roads here. He grew up in Charlotte and graduated from UNC-Greensboro and married a woman from Warren County. He came to coach and teach, and during the shutdown of the pandemic, he fought for his kids to have a season.

“I get that sense of purpose here,” he said. “Like I have a mission.”

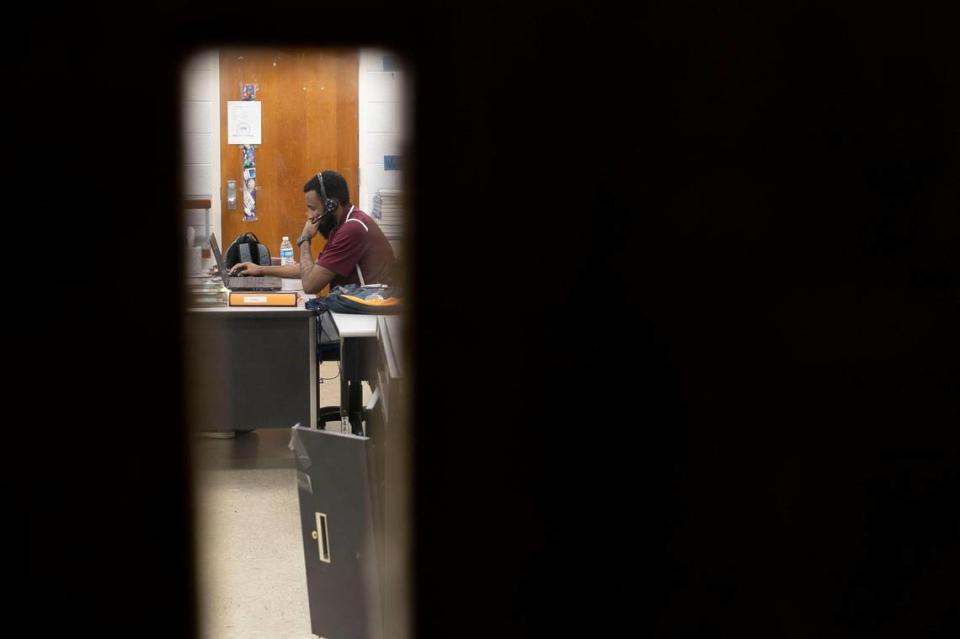

He argued that his players needed basketball. That they needed something other than Zoom classes and the endless wait for normalcy. McRae often saw that need reflected in his computer screen, in the eyes of students he taught, or when he checked his players’ grades.

Months into remote learning, some who were once good students were now barely passing. Others who labored to maintain eligibility seemed to have given up. So much about life here, like everywhere, came to be defined by loss. McRae felt like he was losing some of his kids, too.

For a time it seemed the season would be one more thing gone. Then it began, defying odds. It began with a tryout with but one requirement to make the team: Show up. There were barely enough players for a varsity team. The season began without three players lost to poor grades. It began without another who needed to work to pay bills.

“And he was going to be my starting point guard,” McRae said.

In some places, the toll of the pandemic was best measured by the number of virus cases or deaths. In Warren County, where the lack of population density has kept those numbers low, the cost was less quantifiable but damaging in different ways. Life was a challenge before and now the moment had magnified inequities.

“When (people) see a 100-point loss, it’s like — what are those guys doing?” Bryan Fuller, one of the Eagles’ assistant coaches, said recently. He was a Warren County native. “But you don’t see that every day they might be fighting to have a meal. Or parents working two or three jobs, or laid off at some point because of the pandemic. So you’re dealing with the poverty issue.

“It’s so much that these kids go through, and I commend all of them for continuing to come in here. ... They feel like they’re losing at life because things aren’t going well at home, and then they come here and they’re also not having as much success. But every day they’re continuing to fight. And I commend our kids so much just for showing up.”

Basics taken for granted elsewhere were not givens here. Access to a computer, for instance, or a high-speed internet connection. In Warren County, the school year was delayed a month while administrators secured laptops and internet hotspots for those in need. Once class began, McRae soon noticed a lot of his players’ grades plummeted.

Warren County High received a “D” grade in four of the past six years, according to data from the North Carolina Department of Public Instruction. In the past five years for which data is available (2014 through 2019), the school failed to meet the state standard for academic growth.

Fewer than 10% of incoming 9th graders arrive as “proficient,” as defined by the state. Nearly half the students are considered economically disadvantaged. The county has one of the highest dropout rates in North Carolina, according to the most recently-available data, and only 50% of Warren County students go on to any kind of college, below the state average of 62% and far below a place like Wake County, where 72% of high school seniors enroll in a college.

It was another number that most bothered McRae, and that was the one that quantified teacher turnover. A 2019 N.C. State study found that Warren County schools lost one-third of their teachers after the 2017-18 school year. More than once last year, McRae’s first, his players asked if he’d be back or if he’d be another in the revolving door, leaving them behind.

“And it didn’t really dawn on me of why they were asking me that,” he said, until the end of the year when he witnessed the exodus among his colleagues.

He envisioned staying for a while and being a part of a solution and, on a recent Friday, a couple of weeks after the 103-point loss, he gathered his team inside a classroom in the late afternoon for a film session. The Eagles were 0-6 now and soon they’d be 0-7, and then 0-8, and McRae sat at the front of the room, replaying highlights and lowlights while his 10 players sat quietly in front of him, all wearing facemasks while they watched another defeat unfold.

“That is our kryptonite, protecting the ball,” McRae said, replaying another turnover, and for several minutes he spoke with an urgency: “Every game is the same story, is it not? ... Are you Steph Curry? No, you’re not Steph Curry ... Everything you do with your right hand, start doing with your left ... Another turnover — like, are y’all even looking at each other?”

And then, finally: “A new season now. Let’s go 1-0 tonight.”

On the wall to his players’ right there was a large bulletin board that hung underneath colorful letters that spelled out “DREAM BIG.” It was, literally, a wall of dreams, a place for students to pin their goals, and the ones on the board had been there since last March. Students at few high schools in the state faced longer odds than those here, but their visions were no less grand:

Graduate high school and get into UNC ... Own my own restaurant ... Build up my career and become my own CEO of a law firm ... Being a famous YouTuber ... To be a chef and to make money ... Become an architect. ... Buying my mom her dream house. ... To be in the NFL.

One student’s dream was more humble: “Walking across the stage with a high school diploma.”

McRae and his players walked out of the room, past a trophy case without many trophies, past the signs near the lobby promoting in-state colleges. They stepped out into the cold, several teens piling into one small car, and rode to a nearby rec center that hosted their home games while their school gym was being renovated. On this night they had no locker room to change in and they trailed by 30 in the first quarter.

Just playing was its own kind of victory.

**

In a moment of loss, and going without, what did it mean to lose a basketball game by 103 points? McRae and his players have had time now to think about it. Carter, the Eagles’ sophomore guard, predicted he’d remember it as long as he lived. Every day was, for him, a story of determination.

He lived in Macon, a dot on a map off of Highway 158. He lived in an area so removed that he described it in terms of drive-thrus: “We’ve got a Hardee’s and Burger King,” he said, and that was it.

Carter lived near three churches, one Methodist and two Baptist on one side of the road. Across the street, there was the Post Office, just next to the abandoned Macon General Store,

What there was not, Carter said, was a reliable internet connection. The county gave him a hotspot for school but it didn’t work given the lack of a strong cellular signal. He woke up early every morning to accompany his mom while she worked at a scrap metal and auto parts shop off the side of a country road.

The dirt lot, muddy in parts, served as a graveyard to rusting Chevys and Fords, junkyard cars in every direction. Inside the garage, Carter went to school from a second-floor loft, the sound of machinery and mechanics competing with the voices of his teachers. The place smelled like cigarettes and the inside of an old van. Used tires and engines covered the floor downstairs.

A thin layer of red clay dirt covered the desk where Carter sat, and just about everything else. On the floor, he’d placed a sleeping bag and some pillows for naps during breaks. This had been his classroom every day for months, the easiest way for him to access the internet on the laptop his mom rented from his school for $20, and was due back at the end of the year.

His morning began with virtual gym class — stretching exercises over the webcam — and now, in the afternoon, Carter logged into his masonry class, where the teacher was talking about hammers and jointers and levels. In one way, Carter said, maybe it was good that this was how he had to learn, in the sort of place he didn’t want to wind up.

“It makes him decide that he wants to go to school and get an education and not have to be out here doing grunt work, basically,” his mom, Clancy Carter, 42, said downstairs while she checked inventory on her desktop. She was proud of his 4.3 GPA; thankful he still had a basketball season, at least.

“The kids need an outlet,” she said, while bemoaning the lack of those outlets for kids her son’s age. “That’s life around here. They’ve got nothing to do.”

Not too far down the road, at the county’s outdoor rec center, the basketball rims were still off the backboards to keep people apart. The gym where the Eagles now practiced and played had been closed for much of the past year, too. After the 103-point loss, they’d shown up there and had one of their best practices, McRae said.

“A lot of our kids haven’t seen a lot of success.,” said V.J. Hunt, one of McRae’s assistants who was also the Eagles’ football coach. “It’s kind of hard to inspire, in our environment. It’s kind of hard to sometimes inspire them because they see what other places are doing sometimes. ...

“It’s been a few times where we may go to another school and the kids (are) like, ‘Hey coach why we don’t have that, you know what I mean?”

Now, Hunt said, “the beauty in it is that our kids come to fight every day, regardless of what they are up against.” He thought it made them better. He hoped. McRae, meanwhile, expected a conference championship in two years. During a recent practice he gathered his team and said, of the 103-point margin:

“I promise y’all we’re going to look back on this and we’re going to laugh about it,”

On the night it happened, he and his guys knew, to an extent, what might be coming. Warren County is a 1-A school, along with the others with the smallest enrollments. South Granville is one level up, and it was among the best 2-A teams in the state last year and again this year. One of its players, Bobby Pettiford, has committed to play at Louisville, an ACC school with a national championship pedigree.

Warren County, meanwhile, has no such prospects. As the margin grew Carter said, the score “started to mess with me.” One of his teammates, another sophomore named T.J. Williams, said, “People just wanted to stop playing .”

It became a dilemma for McRae. South Granville scored 35 points in the second half after 82 in the first, yet McRae still questioned the sportsmanship. He said South Granville continued to push the pace, that it took quick shots and pressed and pressured his overmatched team, already defeated.

“Cold-hearted,” was how Carter put it.

“It got to a point where integrity was lacking on their end,” McRae said, “and there was a mission to embarrass kids, in a sense.”

He said he spoke the next day with Jake Wohlfeil, the South Granville coach and athletic director. There was no apology, McRae said. To the contrary, he said, “If I’m being honest, he was confused at what he did wrong.”

In an email to The News & Observer and Charlotte Observer, Wohlfeil wrote that “we have moved on from that game,” and that “we are not interested in the record in any capacity.”

“We wish Warren County the best of luck going forward,” Wohlfeil wrote, and he didn’t respond to another request to talk. In the moment, McRae thought about everything his players had been through — the lack of meals, for some, and the lack of reliable internet, for several, and all the things that came with life here, anyway, in a place kids are so eager to leave, if they can.

Part of him wanted to walk off the court with his players in protest. But then, McRae said, “I hate quitting, more than anything.”

Afterward, officials from the North Carolina High School Athletic Association decided not to include the score in the record book. They decided to discontinue the largest margin of victory record. And so Warren County’s defeat will not be preserved for posterity. It might, in fact, fade away and be forgotten, except among those who experienced it.

McRae had asked his players to remember. To bottle away the feeling that night. He hoped there could be value in the experience. He came to accept a thought that could help us all navigate the defeats of these times: That the losses of today, no matter how great, can help fuel the victories of tomorrow.