Looking Back: Chillicothe declares war on rats in 1924

Early evening, April 14, 1924, John Knecht stood behind the counter of the South End Meat Market at Paint and 8th streets and dropped a chunk of hamburger steak on the butcher’s block. Wiping his left hand on his bloody apron, his right hand picked up a large knife off the counter. The veteran butcher made a sweeping motion with his arm and skillfully sliced off a small piece of the meat.

Next, he reached for a cardboard tin can, twisted off the lid and carefully sprinkled a white powdery substance on the raw meat. Turning to the sink, Knecht twisted on the faucet and filled a water glass half full. He drizzled drops of water on the red meat, simultaneously chopping and mixing it with the knife until the mixture had the consistency of a moist mush. Satisfied, he disappeared, returning moments later with a small brown paper bag and a pen. In big capital letters he scrawled “POISON” on the side of the bag. Knecht snapped the bag open with a practiced flick of the wrist, scooped up a morsel of the mush with the knife, dropped it into the sack and twisted the top closed.

The same scene was playing out across the city that long ago Monday evening. Inside bakeries, dairies, groceries, meat markets and restaurants, store owners and their employees were sprinkling barium chloride on slices of apple, cake, cheese, fish or other recommended baits. No matter the bait used, though, they were all busy preparing the opening salvos in Chillicothe’s first official war against Mr. Rat.

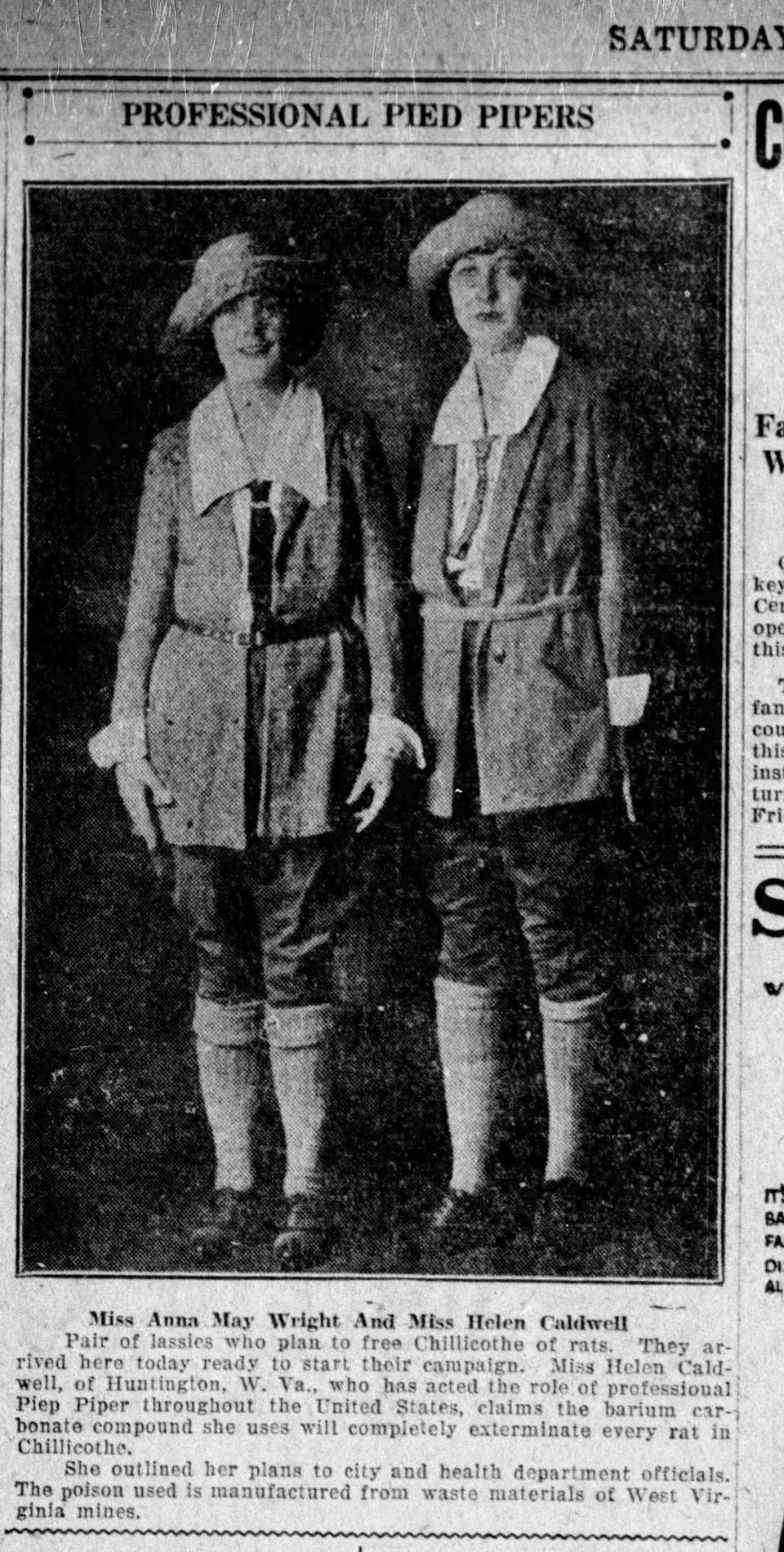

Two months before, Helen Caldwell and Anna Mae Wright, two young women who were gaining national fame, stopped in Chillicothe and appeared before the Health Department and Chamber of Commerce. Caldwell and Wright, often described as charming, pretty, and a couple of modern-day pied pipers, pitched a plan to exterminate the city’s rodent population. The two rat exterminators were receiving much press attention as they traveled from the Atlantic to the Pacific and from North to South conducting successful rat killing campaigns in hundreds of towns and cities.

Part of their appeal was they were challenging gender stereotypes by engaging in an occupation completely dominated by men. However, numerous magazine articles, Sunday features and newspaper columns about the women often veered off to the topic of their good looks. One newspaper columnist had this to say, and it perfectly sums up the kind of attention Caldwell and Wright were receiving: “We regret that we have not their pictures to print, showing the color of their hair, because we believe a woman, or women who will stand pat during a battle with rats and mice and not mount the top of a chair or table during such a drive, is entitled to a Carnegie medal. In the meantime, the public will keep one eye on the rodents and the other on the nervy, fair exterminators.”Caldwell and Wright were in Ohio for much of February and word of their success spread fast. In the weeks before stopping in Chillicothe, they visited Circleville, Gallipolis, Lancaster, Marietta, Point Pleasant and Pomeroy. The Gazette printed pictures of the women, but otherwise its coverage focused on their proposed plan, which was endorsed by the Department of Agriculture.

The plan required close cooperation between local government and the business community, but if this could be accomplished the women promised the near elimination of the city’s rodent population. Getting that cooperation, however, was quite a task in the days before supermarkets and large department stores. Chillicothe was dotted with dozens and dozens of small meat shops, bakeries, candy stores, dairies, fish and poultry houses, groceries, restaurants and more. For the most part, the proprietors of these shops were on board.

The city health department promised to bait all garbage dumps, canal banks and harbors, but asked that all “wholesale houses, bake shops, groceries, butcher shops and everybody interested join with us at the same time and thus rid the city of rats.” It recommended the powdered barium chloride sold by Caldwell and Wright be used because it had the advantage of being “slow in its action so the rats affected by it have time to leave the premises in search of water and return to their burrows before they succumb.”

At least one woman was up in arms about using poison, almost certainly after learning that pets had been accidentally killed in Circleville after eating the poisoned bait traps. The Gazette, though, had a harsh answer for her: “The results achieved by the rat extermination campaign will far outweigh the loss of any pets,” the paper scolded. “If people keep their dogs, cats and chickens on their own property as they should be kept, there will be no trouble.” Not another peep was heard.

Rats are nocturnal animals, so the plan was to place the bait out at night when the rats were searching for food. The health department suggested the most convenient and successful method was to place the bait in paper bags as Knecht did and drop them in places frequented by rats. In addition, the department instructed, “Fresh bait should be distributed each night and bait not eaten should be taken up and destroyed each morning.”

On the first night of the scheduled weeklong war on the rodents, John Knecht and the other small shop owners likely prepared only a handful of traps, but the health department prepared hundreds of the poisoned bags and placed them in one garbage dump north of the Scioto River close to the head of Bridge Street and another at the South Paint Street dump. The next morning, however, none of the bait had been touched at the Bridge Street garbage dump because recent flooding had likely driven them away. However, the bait in many sacks were missing at the Paint Street dump. By the last day of the war on Mr. Rat, the poisoned bait was mostly untouched, and the Gazette speculated that it was because the rats “had eaten contents of sacks put out earlier in the week and died.” It seems Chillicothe’s first official war on Mr. Rat was a success.

This article originally appeared on Lancaster Eagle-Gazette: Chillicothe goes on rat-killing campaign in 1924