Looking back at Flint crisis, Harris rolls out 'water justice' program

Presidential elections are decided by many things: media exposure, financial backing, personal chemistry, timing and luck. Policy positions often are just a way of signaling where a candidate stands on the political spectrum. But 2020 is shaping up to be different, the most ideas-driven election in recent American history. On the Democratic side, a robust debate about inequality has given rise to ambitious proposals to redress the imbalance in Americans’ economic situations. Candidates are churning out positions on banking regulation, antitrust law and the future effects of artificial intelligence. The Green New Deal is spurring debate on the crucial issue of climate change, which could also play a role in a possible Republican challenge to Donald Trump.

Yahoo News will be examining these and other policy questions in “The Ideas Election” — a series of articles on how candidates are defining and addressing the most important issues facing the United States as it prepares to enter a new decade.

For most of the past century, Americans in most cities could take for granted the safety, cleanliness and availability of their drinking water.

But over the past several years, a number of high-profile incidents — from the California droughts to the Flint, Mich., pollution disaster — have highlighted the limits of the nation’s water supply and the impacts of environmental changes, pollution and aging infrastructure on water quality.

In 2014, 40 out of 50 state water managers predicted that some portion of their states would face freshwater shortages within the next decade. One recent study by the nonprofit Environmental Working Group and Northeastern University, which compiled data from the Pentagon and water utility reports, found that approximately 19 million people across 43 states are exposed to contaminated drinking water.

Meanwhile, the cost of drinking water is on the rise, with some researchers predicting that one-third of American households could be unable to afford their water bills within the next few years.

Before the Federal Water Pollution Control Act of 1948, which allowed for state and local governments to receive federal funding, research, planning and technical assistance for sanitary infrastructure, the federal government played virtually no role in the supply and regulation of water in the United States.

A 1965 amendment imposed uniform water quality standards. In 1972, the Clean Water Act imposed treatment requirements for industrial and municipal sewage to protect freshwater sources. The Safe Drinking Water Act of 1974 required the Environmental Protection Agency to draw up health-based standards for all drinking water provided by public water systems, and identified contaminants that must be monitored and reported to the public if they exceeded certain levels.

Under the 1974 law and subsequent amendments, the EPA has developed a system for state and local oversight of water systems to ensure compliance with national standards and to notify residents of hazards.

More than four decades after the passage of the Safe Drinking Water Act, major failures by the EPA would be identified as contributing to the contamination of the public water system in Flint and the lack of notice to the public, creating a national emergency and a public health crisis, the full effects of which are still unknown.

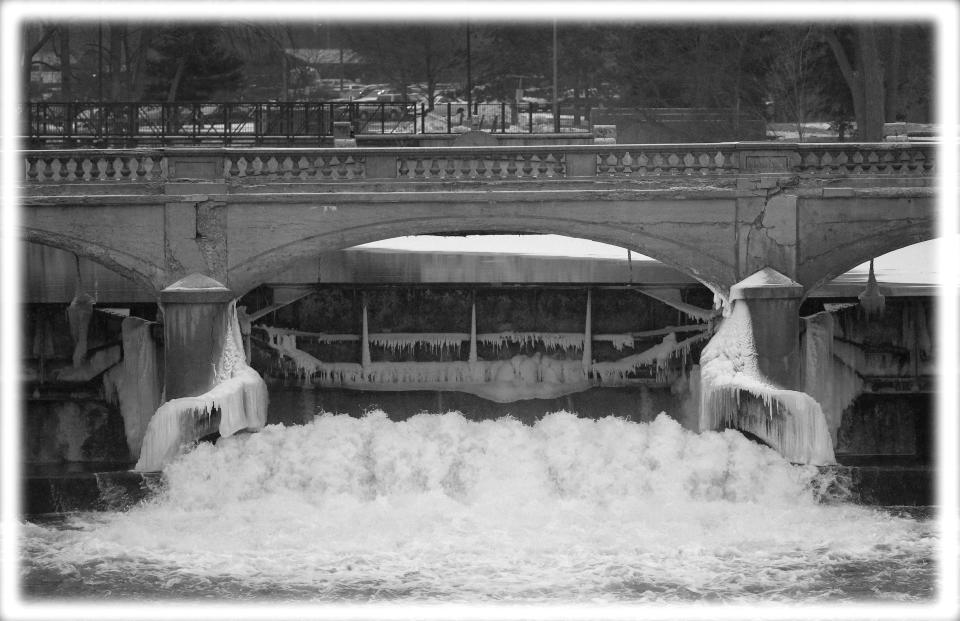

The origins of what is now known as the Flint water crisis are rooted in a cost-saving scheme by state and city officials to switch Flint’s water source from the Detroit Water and Sewerage Department to the Flint River in April 2014. While that decision, and the subsequent actions — and inaction — by various officials that followed may have been specific to Flint, the catastrophe that ensued revealed a number of underlying risks to water systems around the country, especially in low-income and minority communities.

Though Congress officially banned the use of lead pipes, fitting or solder in new plumbing installations in 1986, a study conducted 30 years later by the American Water Works Association estimated that 6.1 million lead service lines built prior to ban were still being used to deliver water to households nationwide. Investigations spurred by the crisis in Flint uncovered similar stories of lead poisoning and insufficient government response in several other cities, such as Newark, N.J., Milwaukee, Detroit, Chicago and Baltimore. One report by CNN found that more than 5,000 systems providing water to approximately 18 million people in the U.S. were in violation of the EPA’s lead regulations.

Lead is hardly the only contaminant that poses a threat to drinking water in the U.S. Another report from 2019 found various other toxic chemicals in drinking water in nearly every state in the country.

The fallout from Flint’s water contamination crisis also offered a glimpse at another issue facing families across the United States: the rising cost of water.

Well before toxic levels of lead had leached into their taps, Flint residents — roughly 40 percent of them living in poverty — had been getting hit with some of the highest water utility fees in the country. As Yahoo News reported at the time, this continued even after Flint’s poisoned water had become a national scandal, with residents struggling to pay hundreds of dollars each month for water they were afraid to drink, at the risk of having their homes taken away or being accused of child endangerment.

Between 2010 and 2015, household water bills increased by 41 percent in 30 major cities.

According to a 2017 study by researchers at Michigan State University, 11.9 percent of American households — approximately 14 million — could not afford their water bills in 2014. If costs continue to rise at the same rate over the next five years, they predicted, that percentage could triple, leaving one-third of American households without access to affordable water.

Last week, Democratic senator and 2020 presidential hopeful Kamala Harris partnered with Reps. Dan Kildee of Flint and Brenda Lawrence, whose Michigan district includes much of eastern Detroit, to introduce the Water Justice Act. The proposed legislation outlines a $250 billion plan to revamp the country’s water infrastructure to provide guaranteed access to a safe, affordable and sustainable supply.

“We must take seriously the existential threat represented by future water shortages and acknowledge that communities across the country — particularly communities of color — already lack access to safe and affordable water,” Harris said about the bill, which would dedicate $50 billion to conduct lead testing and replacement of toxic infrastructure, such as pipes and drinking fountains, in low-income communities and schools with high levels of lead in the water. The proposal also includes $170 billion for more preventive programs under the Clean Water and Safe Drinking Water acts to better protect high-risk communities from exposure to lead and other toxic contaminants through drinking water.

The bill also calls for the creation of a $10 billion fund to subsidize water bills in low-income households deemed to be “environmentally at risk” based on their proximity to sources of pollution. Another $20 billion would be dedicated to a variety of programs aimed at the sustainable supply, recycling and conservation of drinking water.

Harris is not the only 2020 hopeful to take on the issue of clean drinking water. Other Democratic candidates such as Joe Biden, Beto O’Rourke, Jay Inslee, Pete Buttigieg and Kirsten Gillibrand have included plans to ensure access to safe drinking water as part of larger environmental proposals. In one section of his campaign website, Andrew Yang declares, “When I’m President, we will invest the resources needed to guarantee clean drinking water to all Americans as a basic human right.”

In an interview with the Root in April, Yang said that, if elected, he would use federal funds to ensure that Flint’s water system was completely fixed and pledged to have his two young children drink Flint tap water once the job was done to prove its safety.

The crisis in Flint, which emerged as a national news story in early 2016, became a major talking point for then-Democratic presidential contenders Hillary Clinton and Bernie Sanders, who even held a debate in the beleaguered city ahead of the Michigan primary. Flint Mayor Karen Weaver spoke at the Democratic National Convention in July 2016, praising Clinton, the nominee, for helping to draw national attention to her city’s plight.

Three years later, Flint — coincidentally located in a must-win state for Democrats in 2020 — seems to be an almost obligatory talking point and campaign stop for Democratic candidates. Over the past few weeks, O’Rourke and Gillibrand have made their way to Flint, as have Sens. Amy Klobuchar and Cory Booker, and Julián Castro, the former San Antonio mayor and secretary of Housing and Urban Development.

In a video announcing his late entry into the 2020 field, businessman Tom Steyer included an image of the Flint water tower.

Though some Flint residents and local officials have reportedly expressed skepticism about becoming just another stop on the presidential campaign trail, recent polls show that clean drinking water is an issue of major concern for Michigan voters as well as Americans nationwide.

“There is not a single issue in this election that is more important than the fact that in 2019, in the United States of America, there are millions of people who do not have access to clean, safe and affordable water for themselves, their families, and their children,” Laura Rubin, director of the Healing Our Waters-Great Lakes Coalition, said in a press release last week. The coalition, composed of more than 160 local, state and national environmental organizations, has called on 2020 presidential candidates to support a platform to protect and restore the Great Lakes, which supply drinking water to more than 30 million people.

Ahead of the second round of Democratic debates in Detroit this week, five Democratic governors from the Great Lakes region, led by Michigan’s Gretchen Whitmer, echoed the coalition’s call for presidential candidates to get behind the platform, which includes increasing annual funding for the Great Lakes Restoration Initiative to $475 million and tripling federal spending on infrastructure for drinking water and wastewater treatment.

“These are not Democratic or Republican issues,” Whitmer told the Associated Press on Monday. She said she and Govs. J.B. Pritzker of Illinois, Tom Wolf of Pennsylvania, Tony Evers of Wisconsin and Tim Walz of Minnesota were hoping to get President Trump’s support for the platform as well.

“This is about protecting this incredibly important resource that you can’t live without,” Whitmer said.

Download the Yahoo News app to customize your experience.

Read more from Yahoo News: