'Long overdue': Emmett Till Antilynching Act signed with Eddie Jones and LaSimba Gray present

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Two prominent Memphians were present at the White House today as President Joe Biden signed the Emmett Till Antilynching Act into law.

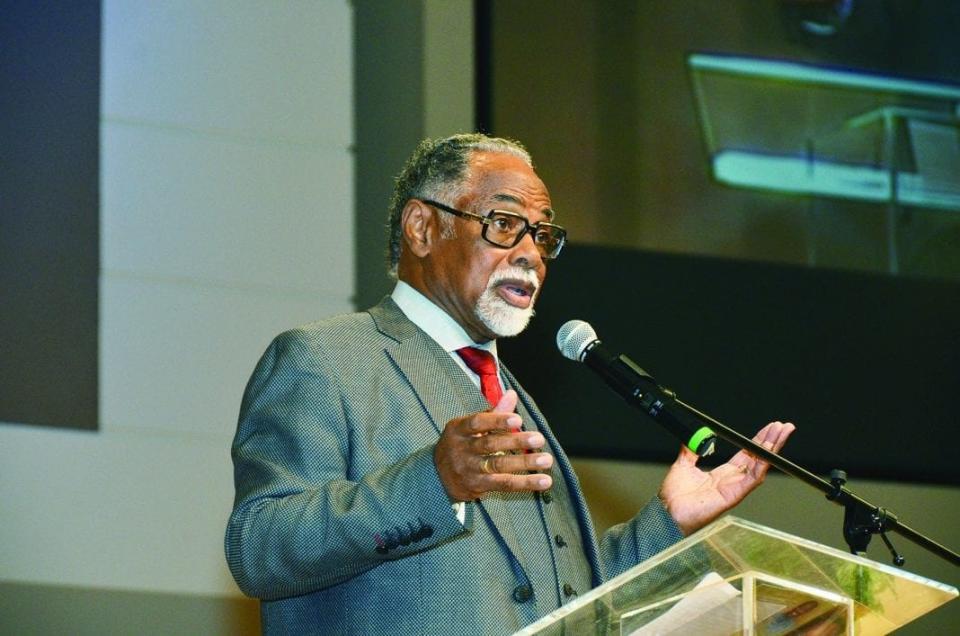

Shelby County Commissioner Eddie Jones Jr., also president of the National Association of Black Officials, and the Rev. LaSimba Gray, chair of the Ida B. Wells Memorial Committee and former pastor of the New Sardis Baptist Church, were both invited to the White House to witness the historic signing of the bill Tuesday.

Before traveling to Washington, D.C., Jones said it would be a "wonderful thing" to finally see lynching made a federal hate crime, even if it is now the year 2022.

"I'm honored to be called out to go and join our president as he signs this historical legislation and it has been long overdue," Jones said. "There's a lot more that needs to happen."

Congress first considered an anti-lynching bill in 1900, when it was introduced by Rep. George White, R-North Carolina, the only African American then in Congress. The effort was unsuccessful. Since then, more than 200 anti-lynching bills have been introduced by members of Congress, but all have failed.

On March 9, 2022, the Senate unanimously passed legislation making lynching a federal hate crime, less than a month after the House passed the bill.

The act is named after Emmett Till, a 14-year-old African American boy who in August 1955 was abducted, brutally beaten and shot after being accused of whistling at a white woman at a store in Money, Mississippi. An all-white jury found the men who had killed Till not guilty of his murder, although a year later they publicly admitted they had killed Till.

Several decades before Till's murder, African-American journalist Ida B. Wells wrote about the terror of lynching and pursued anti-lynching legislation. After the 1892 lynchings of three grocery store owners in Memphis, one of whom was a friend, she began to document lynchings across the South, work that led to her being driven from Memphis by white mobs.

“It is fortuitous that 130 years after the death of anti-lynching activist, Ida B. Wells, the family of Wells can claim some measure of victory as President Biden signs the Anti-lynching bill into law,” Gray said in a statement. “This law serves as validation that Ida B. Wells dramatically changed the course of history.”

Wells’ great granddaughter, Michelle Duster, who was in Memphis Monday for the official unveiling of a street named for the crusading journalist, was also present at the White House ceremony.

A 'critical step toward justice': Senate passes the Emmett Till Antilynching Act

In other news: Ida B. Wells fled Memphis due to racism. Now she has a street named after her.

The Emmett Till Antilynching Act passed the Senate unanimously. It allows crimes to be prosecuted as a lynching if a victim is killed or injured as a result of a hate crime. The companion legislation was approved in the House on a 422-3 vote, with three Republicans, Reps. Andrew Clyde of Georgia, Thomas Massie of Kentucky and Chip Roy of Texas, voting against the bill.

During the ceremony Tuesday, Biden stressed that the new law "is not just about the past."

"It’s about the present and our future as well," Biden said. "From the bullets in the back of Ahmaud Arbery to countless other acts of violence, countless victims known and unknown, the same racial hatred that drove a mob to hang a noose, brought the mob carrying torches out of the fields of Charlottesville just a few years ago. Racial hate isn’t an old problem. It’s a persistent problem. A persistent problem.”

Vice President Kamala Harris made similar remarks.

“Lynching is not a relic of the past," she said. "Racial acts of terror still occur in our nation, and when they do we must all have the courage to name them and hold the perpetrators to account."

From 1877 to 1950, about 4,400 Black people were lynched in the U.S., according to the Equal Justice Initiative, a Montgomery, Alabama-based nonprofit that offers legal services to those who are wrongly convicted of crimes, among others. The NAACP counted about 4,700 lynchings from 1882 to 1968, and more than 70% of those killed were Black.

Both organizations noted that the numbers probably were underreported.

USAToday contributed to this report.

Katherine Burgess covers county government and religion. She can be reached at katherine.burgess@commercialappeal.com, 901-529-2799 or followed on Twitter @kathsburgess.

This article originally appeared on Memphis Commercial Appeal: Jones, Gray visit White House for signing of antilynching act