Crossrail's army working underground for new London railway

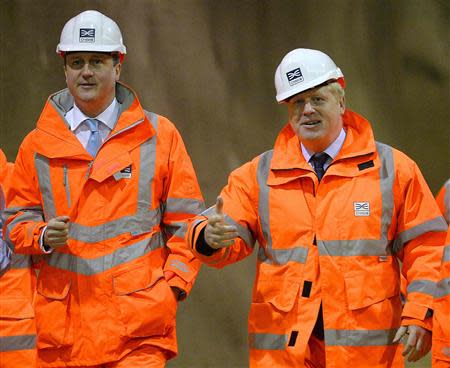

By Sarah Young LONDON (Reuters) - Bomb disposal experts, archaeologists, tunnellers and eight very special machines with names like Phyllis, Ada and Elizabeth help make up the army working underground to build a new underground railway cutting through historic London. Crossrail, a 15 billion pound railway link connecting east and west London and Europe's largest infrastructure project, will open in four years' time and is now half complete, on budget and on schedule. The new railway across London will be the realisation of a plan first mooted in the 1880s to connect the docks in the east of the city to Paddington in the west. Crossrail however will go further, linking Heathrow airport and the commuter strongholds of Maidenhead to the west with Shenfield, on the outskirts of Brentwood in Essex, to the east. Leading the charge underground are the eight giant tunnelling machines, measuring longer than a football pitch and just under twice as tall as a double decker bus, and in the mining industry's superstitious tradition, all given female names. "When one comes crashing through the wall in front of you, it's a pretty special sight," said construction manager Will Jobling, 31, as he recalled Elizabeth's latest achievement under Stepney Green in east London. Elizabeth and her sister tunnelling machine Victoria, were named after The Queen and her great-great-grandmother Queen Victoria, while Phyllis is named after Phyllis Pearsall who created the first London A-Z map, and Ada after Ada Lovelace, one of the earliest computer scientists. Two tunnelling machines under the Olympic park, Jessica and Ellie, pay homage to two of Britain's stars from the 2012 games, Jessica Ennis-Hill and Ellie Simmonds. Tunnellers and workers gather to watch, celebrate and record on their mobile phones the moment when a tunnelling machine breaks through a temporary concrete plug, marking the completion of a section. Of the 42 km of new tunnels, over two-thirds have now been dug, but Crossrail's chairman Terry Morgan said substantial engineering challenges still remain to complete what he sees as a project of unprecedented scale and complexity. "We've looked at some of the big investments that have been made in China, but nobody's tried to do what we've been doing which is to build a new railway under a really old, global city like London," he said. For Morgan, a former managing director at bluechip defence firm BAE Systems, only the scale of London's Olympic Park compares, but not really: "we're twice as big as that and it's more intrusive". Prime Minister David Cameron made his third visit to Crossrail on Thursday while delegations from the Middle East, the Far East, the U.S, Russia and Scandinavia have all come to see how London is doing it. Crossrail is part of a new-found momentum for infrastructure projects, said Morgan, following Heathrow's terminal five, opened in 2008, the Olympic Park, and proposals for a new north to south high speed railway (HS2) line in Britain. "It's a growing reputation that the UK is now building," he said, adding that Crossrail's on-budget, on-time progress could help smooth the passage for the HS2 project, which has been the subject of angry protests. Recent estimates point to Crossrail, which is primarily funded by the public sector, adding more than the forecast 42 billion pounds to Britain's GDP, said Morgan. Sweden's Skanska and British firms Balfour Beatty, Costain, Morgan Sindall and Laing O'Rourke are all involved in the project on which 10,000 people currently work. HISTORIC TREASURES Digging the tunnels, which at their deepest are 48 metres below the surface and weave above and below the routes travelled by London's crowded tube trains, is shedding new light on the capital's two thousand year history. Since work started in 2009, construction workers have uncovered 20 Roman skulls which possibly date back to the time of a revolt led by Queen Boudicca against the Roman occupation of Britain in the 1st Century. A graveyard which might hold the remains of some 50,000 people killed by the "Black Death" plague more than 650 years ago has also been found and work will start on excavating 3,000 skeletons from another burial ground next year. After the waste mud has been dug out and sifted for relics and artefacts, it is moved out of the capital at the rate of four trainloads a day. It is then taken east by rail and lifted onto ships before being transported to Wallasea Island in the Thames Estuary. The project is not solely based on digging new tunnels. As it snakes its way east under the Docklands, where the Thames widens and the London's shiny financial skyscrapers give way to evidence of its industrial past, the Crossrail route will return to use an old Victorian tunnel, the Connaught Tunnel, which was bombed in 1940 during World War Two. London's docklands, once full of steamships bringing tobacco and meat from the Americas in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, were bombed heavily in the war. So amongst those working for Crossrail are bomb-disposal specialists probing the area for unexploded devices which might have sunk into the soil in the 1940s. In addition to the rail link proper, Crossrail will bequeath to future generations its own relics. At least two of the tunnelling machines will have working parts, oil and lubricants removed and their shells left alongside the tunnels, deep under London. (additional reporting by Andrew Winning; editing by Stephen Addison)