Local history: Demolition begins at former Atlantic Foundry

The Rust Belt is losing a cold slab of Akron-made rust.

On Thursday, wreckers began to demolish the former Atlantic Foundry Co. complex between Beaver Street and Annadale Avenue.

Once Akron’s largest foundry, the abandoned 254,000-square-feet complex has become a safety hazard and public eyesore. City, county and state officials are celebrating the building’s demise, calling it a major milestone in Akron’s revitalization.

The blighted 13-acre site has been a barrier to economic growth, Summit County Land Bank Executive Director Patrick L. Bravo said, and the demolition will pave the way for new opportunities.

There was a time, though, and not too long ago, when Atlantic Foundry was a proud symbol of Akron’s industrial greatness.

Atlantic Foundry began in 1905

Charles Reymann Sr. incorporated the business in 1905 with fellow European immigrants Philip Willenbacher Sr., Fred Spalding, Emil Krill and Evald Erickson. They selected Reymann as president, in part, because he spoke better English than the others.

The men named it Atlantic Foundry Co. as a tribute to the magnificent ocean they had crossed in search of better lives.

Reymann was born in 1869 in Alsace-Lorraine, a German territory in what is now France. He came to the United States in 1892, moved to Akron a year later and worked in the foundry at the Taplin-Rice Co. for a decade.

He and his wife, Salome, married in 1906, raised 16 children and built a home on an 8-acre estate off Canton Road in Ellet.

Atlantic Foundry opened with 12 workers in a rented space on Cherry Street, producing iron castings and wrought iron. A fire destroyed the plant within a year, but the burgeoning business quickly rebuilt and soon moved to a new site at 182 Beaver St. in 1910. It added a steel foundry in 1919.

The company’s fortunes soared as the automobile and rubber industries surged in the early 20th century. Atlantic made tire molds, rings and gears for Goodyear, Firestone and other Akron companies.

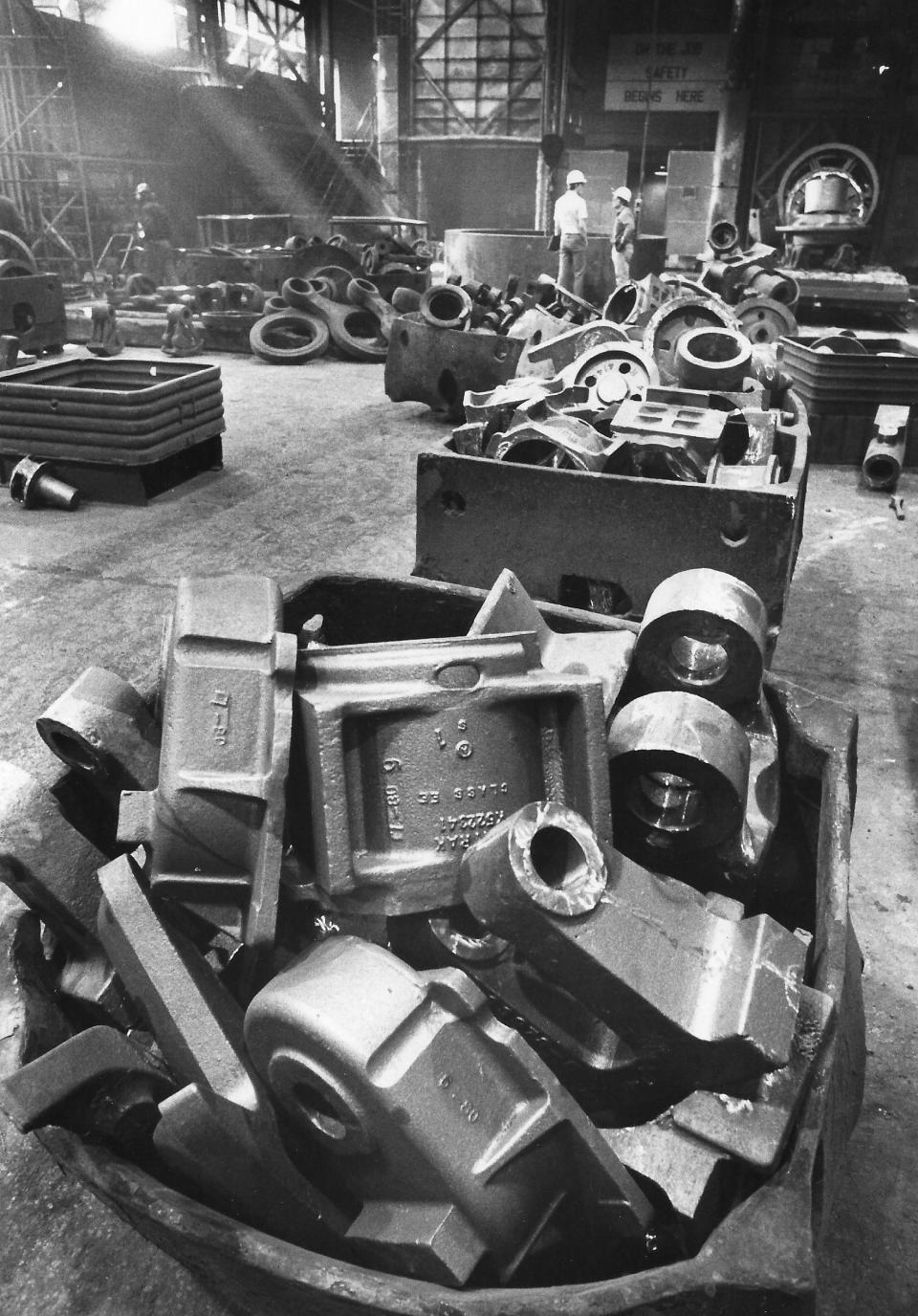

It was hot, noisy, dangerous work. Coated in sweat and gray grime, hundreds of laborers poured bubbling cauldrons of molten metal into molds to create a variety of castings.

“This is one business where you go out and sell the product first and then go to work to make it,” Reymann explained.

Atlantic produced 1,000 tons of steel in 1920. Within 25 years, that number had jumped to 11,000 tons annually. The Akron company reached peak employment of nearly 500 workers during World War II.

Laborers loaded scrap metal onto chutes and poured it into a 4,000-degree furnace. When the metal melted, the crew added shovelfuls of manganese and silicon to make the steel harder and tougher. The furnace tilted and poured metal into ladles that emptied into sand molds to produce gun rings, tank parts, boiler mounts for ships and other materials for the U.S. military.

Akron plant gave ‘Hitler hell’

In a vivid account in 1941, Beacon Journal reporter Anthony Weitzel described it as “a roaring, clanging, smoky inferno turning out a thousand military gadgets to give Hitler hell.”

“Work-grimed vulcans toil inside, moving with sure, certain skill in the midst of a grim clutter of distorted steel,” Weitzel wrote. “They’re deaf vulcans, for ordinary conversational tones and even shouts are drowned in the clamorous flood of foundry noises.

“The furnace roars and whistles and pops and sputters. Grinders scream in the mechanical agony of grinding smooth the tough steel casts. Cranes rumble overhead. Cutting torches hiss and sputter. Pneumatic chisels clang and bang and stutter at the faces of gray-white castings.”

Not only did Reymann help the war effort at home, he sent five sons overseas to defeat Germany and Japan.

Atlantic spent nearly $1.5 million over 15 years to modernize its plant after the war. The company’s steel castings were used in the rubber, steel, automotive and mining industries.

After 50 years of leadership, Reymann stepped down in 1955 and turned the reins over to his son Charles Jr. The elder Reymann died a year later at 86, leaving an estate valued at $300,000 (more than $3.5 million today).

The foundry endured economic recessions, union strikes, industrial accidents, devastating fires and major explosions.

A kiss from ‘Lady Iron’

Supervisor Joe Martinovich, 52, who had worked at the company for more than 30 years, described the scorching environment in 1965.

“Sure you’re scared,” Martinovich said. “But you’ve got to get the heat poured. Besides, what’s fear? It’s like the steeplejack who doesn’t give his job a thought, but would be afraid to stand near this furnace.

“It’s as if we’re sort of daring it — to do what, I don’t know, but we’re daring it sure. And when you pour from the ladle into the molds, you get a few drops down your leg but you just keep on pouring.

“You wince and you think, ‘Lady Iron, you’ve kissed me again!’ ”

Atlantic closed its iron foundry in 1968, converting the entire complex to steel production and focusing on making castings for the rubber, plastic, bearing and earthmoving industries.

Marcel Reymann became president in 1973 following the death of his brother Charles. It was a baptism by fire as the new leader soon faced a strike by United Steelworkers Local 1001 over wages and benefits.

“I’m seeing the dreams and aspirations of a lifetime going up in smoke,” Reymann said at the time. “Things will never be the same.”

But four months later, the union ratified a four-year contract and returned to work.

In 1975, the 70th anniversary of the company, Atlantic employed more than 400 workers and produced about 1,000 tons of steel castings per month. The average casting weighed about 200 pounds, but the largest ones tipped the scales at 18,000 pounds.

The company sank about $3.5 million into equipment during the 1970s to meet federal anti-pollution rules.

“What we do produces a lot of noise, heat, smoke and dirt — and that’s not popular in today’s ecology-conscious society,” Marcel Reymann explained.

Increasingly, Atlantic shipped steel castings to Texas companies for oil drilling and exploration. By 1980, Atlantic’s monthly sales volume was $1 million, a 35% increase from a decade earlier.

An explosion in February 1981 injured 11 workers and blew out walls and windows at the plant. By then, the company employed 275 workers.

Foundry shut down in 1989

The lucrative oil business all but dried up for Atlantic Foundry when energy prices plunged in 1982.

In 1983, Thomas Reymann was elected chairman and president, succeeding his retired brother Marcel.

The company had only five years left.

Despite investing more than $600,000 in improvements, Atlantic Foundry announced Nov. 7, 1988, that it would end operations in early 1989 and lay off the remaining 123 workers.

The company cited the oil industry depression and declining foreign business as reasons for closing. It hadn’t made a profit since 1982.

“We had no choice,” Thomas Reymann said. “It was not a pleasant decision.”

The furnaces went cold and the machinery rusted. Over the decades, the sprawling complex deteriorated as thieves stole scrap and vandals broke windows and spray-painted graffiti. Squatters took up residence.

A Kent State student, 19, was killed in 2012 after falling through the roof while exploring the foundry with three other students.

Something had to be done about the hazardous site.

Demolition begins at old foundry

The Summit County Land Bank acquired the condemned structure in 2020 from its tax-delinquent owner. The land bank received $1.8 million from the Ohio Brownfield Remediation Program to remove waste materials, asbestos and underground tanks before demolishing the building.

Now the old Atlantic Foundry is coming down.

The Summit County Land Bank held a ceremony Thursday along Annadale Avenue as officials honored the foundry’s legacy while emphasizing the need to return the property to a more productive use. The dignitaries took a group photo in front of the doomed building before leading a crowd of about 75 in a countdown.

Then on cue, heavy machinery from Butcher & Son Excavating began to claw away at the foundry. Bricks tumbled noisily to the ground.

Bravo, the executive director of the land bank, said it should take months to complete the demolition. A future use for the property will be determined.

“There’s so much opportunity here,” he said.

Mark J. Price can be reached at mprice@thebeaconjournal.com

This article originally appeared on Akron Beacon Journal: Atlantic Foundry plant demolition begins in Akron