I Loathe Bloomberg. But He’s Doing One Thing Right.

There’s a popular internet meme that routinely surfaces on Twitter and it’s based on a headline from the satirical site Clickhole: “Heartbreaking,” it says. “The Worst Person You Know Just Made A Great Point.” We all know what that feeling is like: resentment that someone horrible said something smart, and begrudging admission that should probably be acknowledged.

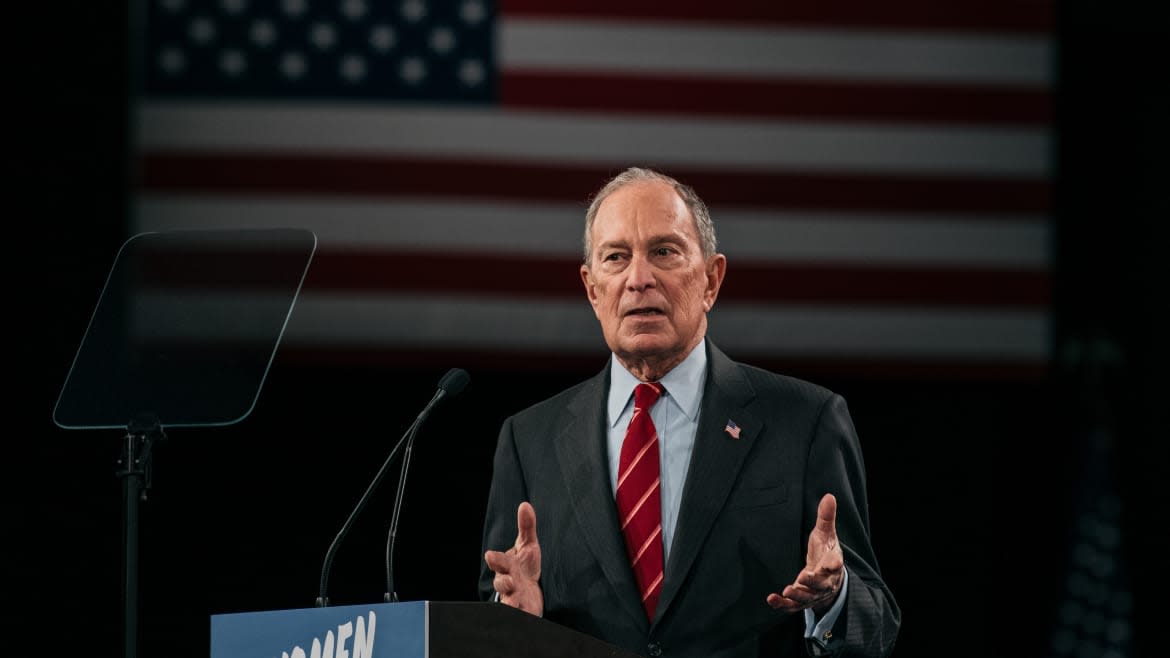

It is with that begrudging resentment (I’m sure there’s a German word for it) that it pains me deeply to say that Michael Bloomberg’s campaign is doing things that Democrats should be doing generally in terms of communicating with voters, and that his willingness to spend large amounts of money on media buys and new technologies is unprecedented, and needed.

I find the idea of Bloomberg as the Democratic nominee repulsive. But if I put my loathing of Bloomberg aside for a moment, there are things that Bloomberg is doing that I believe are and will be incredibly effective. The worst person has some great points—and they should be internalized by Democrats who want to be effective in 2020.

Some context and a disclosure before I get to those points: I run a two-person company called The Insurrection that helps Democrats with digital strategy and polling. We are not working on any presidential campaigns and have no plans to do so in this cycle. And we have a mixed political marriage in any case; I’m a Warren supporter and my pollster business partner supports Bernie Sanders.

I’m also a 20-year New York City resident who lived through the Bloomberg administration, and remembers stop-and-frisk, and Bloomberg’s sexism, and his insistence on a third term for himself, despite his repeated claims that he’d already ‘fixed” the city by the end of his second term. I also believe that no one should be able to buy their way into the presidency, and that it’s fundamentally anti-democratic to do so. (That said, I also believe a repulsive candidate running on a Democratic platform is still better than Donald Trump, and will vote for the Democratic nominee regardless because I think the outcome would be comparatively less harmful than four more years of Trump.)

In Mike Bloomberg, Are Democrats Now Turning to an Authoritarian of Their Own?

Bloomberg is smart about messaging, not because he’s a Machiavellian genius, but because he runs a successful multinational media company whose growth and profitability has been built on similar strategies and tactics, and there’s a precedent for their efficacy in the commercial sector that is unrecognized or discounted in Democratic politics.

First, Bloomberg understands the power of saturation, which by itself, can make even mediocre messaging effective. Commercial marketers know this, and will often produce messaging (read: ads and other forms of marketing to consumers) at a massive scale, with the expectation that only a portion of it will work. This is particularly true on digital platforms where the cost of deployment is extremely low, but we also see it in other mediums. (Think about how much direct mail you get from auto insurers, and how many different broadcast ads you see for Geico.)

As of last week, Bloomberg spent $363 million on cable, radio, and broadcast ads. By comparison, Trump spent $325 million on his entire 2016 campaign. Bloomberg’s digital efforts are equally outsized. In 2020 alone, he’s spent $70 million on Facebook and Google. Trump has spent $43 million, and the next highest spend is Tom Steyer at $27 million.

And it’s not just a matter of not understanding these things: messaging and ad spends in a typical political cycle work backwards from the election, ramping up as the campaign gets closer to election day. As a result, most campaigns are not really talking to voters for as long as they probably should be, if they want their core messages to sink in. This is almost always a finance issue. If a campaign estimates that it has a limited amount to spend, it won’t risk frontloading the messaging for fear that the messaging effect will decay over time, if the campaign can’t keep up the spend. So it’s better to only start spending on messaging when you know you can maintain it.

Bloomberg has a disadvantage on the time front, in the sense that he hasn’t been active the entire cycle. But he is more than compensating for it with saturation because for his purposes, the “customer cycle” is a matter of months. And his primary rivals have not been spending at the levels he is now, so their timeline advantages are not as significant as they would be otherwise.

And this flood the zone approach works. It is also very forgiving. If Bloomberg makes mistakes with messaging, or some of it falls flat, it doesn’t matter that much because the campaign will barrage voters with newer and more ads immediately, and in a variety of mediums.

Recently, Bloomberg’s campaign reached out to an array of Instagram influencers and meme-makers in the hopes that they could buy meme-ified placements in order to get in front of a younger generation of voters. The efforts were met with predictable derision in many corners of the internet—satirical memes proliferated, many of them overtly anti-Bloomberg—but this is the medium’s fault tolerance works in Bloomberg’s favor. If a low engagement voter (read: someone who doesn’t actively follow politics, is largely unfamiliar with the policy platforms of candidates, votes irregularly) is exposed to Bloomberg’s name and one or two key ideas the campaign wants to get across, this kind of strategy can work for them.

And there’s not a lot of tolerance for these missteps in mainstream political operations. The failure of an ad campaign is often conflated with a communications crisis, even when it’s small and blows over quickly. As a result, campaigns are risk-averse and only want to try things they’ve already tested and evaluated to death.

Bloomberg’s try-everything approach may be familiar to Republicans because it’s essentially what Brad Parscale, Trump’s digital strategist, and now campaign manager, did in the last cycle. Parscale’s messaging wasn’t sophisticated or even particularly good. But there was a lot of it. In the last few weeks of the campaign Trump spent $29 million on digital, and by comparison, Hillary Clinton’s campaign spent $16 million. The Clinton campaign, like nearly all political campaigns at the federal level, tightly controlled the message from the top down. By comparison, Parscale was able to try things and experiment—largely because Trump was incapable of an organized top-down approach. The Trump campaign’s chaos helped Parscale’s efforts.

There are also things the Bloomberg campaign is doing that might not be apparent from the outside. They pay people well, for one. Campaign staffers are getting salaries comparable to their top-tier commercial counterparts. This is not just about paying people well on principle (if it is at all); it locks talent in. The campaign is hiring aggressively, for the same reason. If they hire everyone who’s on the market, who will Bloomberg’s rivals hire? And this isn’t limited to individuals; Bloomberg corporate has often expanded rapidly by acquiring entire companies, scooping up boutique media companies and smaller tech firms. There’s no reason to believe the campaign couldn’t or wouldn’t do this as well.

Bloomberg is willing to spend big, generally, in a way that Republicans often do, but Democrats typically don’t. There are Democratic organizations, both formally and informally connected to the party, that finance the development of campaign technologies and marketing efforts at the early stages, but usually in increments of $10,000 to $50,000, and when those companies manage to pull together prototypes, there’s often no money for follow-up funding. (Meanwhile, on the right, the Mercer family is writing $20 million checks to fund one digital media outlet.) If we assume that Bloomberg is running the campaign the way he runs his company—and so far, he is—he will make big bets and he won’t care about occasional failures.

He also understands that the cost of advanced technology, well-developed marketing campaigns, and sophisticated data analysis is not somehow cheaper in politics. People may work on campaigns because they’re motivated by things other than money, but that doesn’t mean you can hire an engineer for a tenth of the going rate, or a large good data set purchased from a commercial vendor is less expensive. And if any candidate is going to pay a few million dollars to get a decent data set that tells him something new about voters, it’s Bloomberg. His core business is built on acquiring and understanding data. On the Democratic side, paying that much for data (or paying for data at all, in many cases) is unconventional. The value isn’t clear to political operatives because they’ve never seen it utilized in politics the way it is in the commercial sector.

I hope that we do not end up with a racist, misogynistic nominee, which I believe Bloomberg is.

‘Cokehead, Womanizing, Fag’: Michael Bloomberg’s Book of ‘Wisdom’ Resurfaces

And to be sure, if the majority of the electorate begins to see him that way, even the slickest campaign operation will not matter. There’s also no guarantee that his media-and-tech-centric approach will be successful in the absence of grassroots support and the kind of large scale volunteer-driven field operations that other candidates, like Sanders, have spent the entire cycle building. It’s hard to rally a passionate engaged base around the potential for technocratic fixes deployed by a candidate whose historical treatment of women and minorities materially violates core Democratic values.

But his strategy and tactics are a proportional response to what the Trump campaign is doing, and they are calibrated for the media and technology environment we actually live in, not some theoretical smaller hypothetical context, where a candidate is competing for attention solely with other candidates. Bloomberg believes he’s competing against everything that commands a voter’s attention, and is willing to spend an almost unlimited amount of money to do it.

Even if Democrats disagree in minor ways with some of Bloomberg’s tactics, it’s important to understand why they work, and what can be learned from them. You do not have to accept The Worst Person in order to acknowledge The Great Point.

Get our top stories in your inbox every day. Sign up now!

Daily Beast Membership: Beast Inside goes deeper on the stories that matter to you. Learn more.