The power went out. Now California might let these gas plants stay open

State officials are poised to decide whether four gas-fired power plants along the Southern California coast should keep running past 2020, in the first major energy decision for Gov. Gavin Newsom's administration after this month's blackouts.

The aging, inefficient facilities are being required to close under a policy meant to end the environmentally damaging use of ocean water for power plant cooling. But energy regulators have been pushing since last year to delay the retirement deadlines, warning that insufficient power supplies could cause Californians to lose electricity on hot summer evenings — the exact situation millions of people found themselves in during two evenings of brief rotating outages.

Even before the blackouts Aug. 14 and 15, the debate over how and when to close the coastal gas plants offered a preview of challenges California will increasingly face as it accelerates its transition away from planet-warming fossil fuels.

One way or another, the coastal plants will close. But climate change activists want to see them shuttered as quickly as possible. AES Corp., a Virginia-based company that owns three of the four facilities, says they're still needed for a few more years to help facilitate the transition to 100% clean energy.

Now that debate has been vaulted into the political spotlight.

“We cannot sacrifice reliability as we move forward in this transition,” Newsom said last week, as he urged Californians to use less electricity to avoid the need for more rolling blackouts. “We’re going to be much more aggressive in focusing our efforts and our intention in making sure that is the case.”

"We failed to predict and plan [for] these shortages, and that’s simply unacceptable," the governor added.

Poor planning helps explain why the State Water Resources Control Board is set to vote next week on three-year shutdown extensions for natural gas plants in Huntington Beach, Long Beach and Oxnard, and a one-year extension for a facility in Redondo Beach.

When the water board approved a rule phasing out seawater cooling in 2010, it gave utilities and their regulators a full decade to come up with replacement energy for these particular gas plants.

But only last year, after California's power grid operator began warning of looming capacity shortfalls on summer evenings, did the state's Public Utilities Commission order companies such as Southern California Edison and Pacific Gas & Electric to buy thousands of megawatts of new supply.

The utilities are responding to that mandate by adding lithium-ion batteries, which can store excess solar power during the day and distribute it at night. But it will take several years to get all those batteries online. That's why energy regulators asked the water board for a deadline extension for the gas plants.

Redondo Beach Mayor Bill Brand, who opposes any extension for the gas plant in his city, doesn't understand how energy regulators weren't prepared for this moment.

"They've known the retirement date for all of these plants for the last 10 years," he said. "What happened with the planning?"

Your support helps us deliver the news that matters most. Subscribe to the Los Angeles Times.

In the long run, utilities should be able to keep the lights on without gas, said Stephen Berberich, president of the California Independent System Operator, which runs the power grid for most of the state.

But doing so will require much more battery capacity than the few thousand megawatts in the works right now, along with many more solar panels and wind turbines to charge those batteries. Other clean energy technologies and more robust conservation programs could also help.

The key, Berberich said in an interview, is ensuring there's enough energy supply at all hours of the day and night, including when the sun isn't shining and the wind isn't blowing.

"You don’t necessarily have to have a gas fleet to do that," he said.

California is aiming for 60% renewable electricity by 2030 and 100% climate-friendly power by 2045, although activists say a faster transition is needed to avert the worst consequences of global warming. Democratic presidential nominee Joe Biden has endorsed a national standard of 100% clean electricity by 2035, a decade ahead of California's target.

Nearly two-thirds of California's retail electricity supply came from climate-friendly sources such as solar, wind, hydropower and nuclear last year. But in-state gas plants still account for about one-third of supply.

The fuel is especially important in the evening, when gas plants ramp up after sundown to replace the power from large solar farms and rooftop solar panels.

"The worst possible thing would be to just continue to limp along on gas instead of doing the work that we need to do," said Deborah Behles, an attorney representing the California Environmental Justice Alliance. "We need to procure more renewables and more storage. That’s what the utilities need to be doing, and not relying on these gas plants."

The proposed shutdown delay for the Redondo Beach gas plant has proved especially controversial.

Officials in Redondo and neighboring Hermosa Beach have argued that California can do without the facility because it contributes a tiny amount to statewide energy reliability.

They've also pointed out that nearly 22,000 people live within one mile of the gas plant, more people than live near the coastal facilities in Huntington Beach, Long Beach and Oxnard combined. Gas plants are less polluting than coal but still emit lung-damaging particulate matter.

In a partial concession to the local opposition, the grid operator and other energy agencies told the water board in May they could support a one-year extension for the Redondo plant, rather than the three years they requested for the other facilities.

Berberich said his support for an extension of just one year hasn't wavered after this month's blackouts.

But he warned another extension could potentially be necessary if California doesn't bring enough new power supplies online in 2021. He called for the state's Public Utilities Commission to make sure that doesn't happen by ordering utilities to buy additional clean energy.

"We owe it to the community there to do the right thing," Berberich said.

AES Corp., which owns and operates the Redondo Beach facility, sold the site earlier this year to a developer who hopes to build retail and commercial space along the waterfront. But the deal allows the energy company to keep operating the facility for up to three years, depending on what the state water board allows.

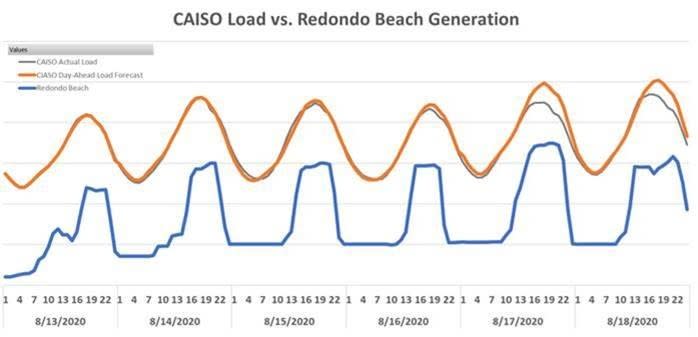

The company is asking for three years. Lisa Krueger, president of AES United States, said a longer extension would allow the Redondo gas plant to serve as an "insurance policy" for California as the state adds cleaner power sources. She provided a chart showing the facility successfully ramped up and down to meet surging electricity demand last week.

"What these units did was exactly what they’re expected and supposed to do," she said.

The Ormond Beach gas plant in Oxnard has been a sore spot for the local community, too.

Environmental justice activists helped kill Puente Power Project, a planned gas plant that could have worsened an ongoing legacy of pollution in the predominantly Latino, low-income city. But Ormond was a tougher battle.

Oxnard ultimately struck a deal with the facility's owner, GenOn Energy Inc., to support a three-year extension in exchange for the company setting aside $25 million to pay for tearing down the plant. City officials are hopeful that getting rid of the hulking industrial facility will help clean up a waterfront that is already home to a massive wetlands restoration project.

"I personally would like to see everything changed tomorrow, but I know that’s unrealistic,” Oxnard City Council member Carmen Ramírez said. "I think the city is making a good choice here. We see something in compensation for having that plant to continue to run for three years."

The state water board is scheduled to vote on the shutdown extensions at its Sept. 1 meeting. Newsom's office didn't respond to a request for comment on whether the governor plans to weigh in.