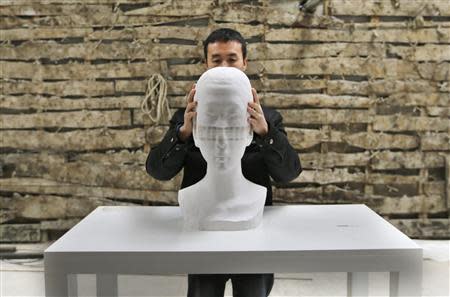

Li Hongbo's paper sculptures stretch the imagination

By Jimmy Jian and Maxim Duncan BEIJING (Reuters) - The line of white, classical busts in Li Hongbo's dusty Beijing studio could be used for drawing practice in any art classroom in the world. That is until the Chinese artist places his hands on one and lifts gently. What had looked exactly like solid plaster is transformed into an amorphous worm. A Roman soldier warps like taffy. A pretty English maid rises abruptly like a ghost before slipping back into place as if nothing had happened. Neither plaster nor clay, the statues are concertinas of thousands upon thousands of fine pieces of paper. "At the beginning, I discovered the flexible nature of paper through Chinese paper toys and paper lanterns," Li, 38, told Reuters on a freezing day in his suburban workshop. "Later, I used this principle to make a gun," he said, casually inverting a crude paper pistol into an elegant fan. "A gun is solid, used for killing, but I turned it into a tool for play or decoration. In this way, it lost both the form of a gun and the culture inherent to a gun. It became a game." Li, who is showcasing some of his recent work at a New York gallery until early March, pastes glue in narrow strips across pieces of paper, which he stacks to the desired height. A head requires more than 5,000 layers. He then cuts, chisels and sands the large block as if it were a piece of soft stone. Born into a simple farming family, Li said he had always loved paper, invented in ancient China. Beyond his sculptures, he has spent six years producing a collection of books recording more than 1,000 years of Buddhist art on paper. Li refuses to embrace the political symbolism and brash social satire that have propelled many contemporary Chinese artists to fame and riches. "I have given myself a rule that my work will not include religious or political themes," he said. "I have no interest in participating in these." LOOK, DON'T TOUCH In recent months, Li has consciously produced only perfect replicas of busts and shapes he used to sketch at university. The before-and-after adulteration may make some viewers squirm but Li says he uses the archetypal figures to make audiences concentrate on the material itself, not to shock. "Strange and unsettling are just adjectives used by some individuals," he said. "People have a fixed understanding of what a human is ... So when you transform a person, people will reconsider the nature of objects and the motivation behind the creation. This is what I care about." Li's exhibition, Tools of Study, at the Klein Sun Gallery in New York, has won him plenty of attention since it opened this month. As white-gloved staff twist and pull busts of Russian writer Maxim Gorky, the Greek goddess Athena and Michelangelo's David out of human form, some viewers also yearn to get their hands on the pieces. "It becomes a dynamic thing versus a very static thing. But as an observer, I can only enjoy that movement of the object if someone opens it for me," said gallery visitor Lydia Chrisman. "You kind of want to play with it. But you can't." Li is aware of this irony and, at a show in Sydney, he provided small models for the audience to fiddle with. "I really want to let them move the pieces. But the gallery won't let people touch them," he said. "If the public were really careful, I would hope they could participate, because only by feeling with their hands could they experience the real pleasure of the material and the form." (Additional reporting by Reuters Television in New York; Editing by John O'Callaghan and Clarence Fernandez)