LGBTQ+ groups help Indiana families find gender-affirming care despite statewide ban

Editor's note: This story has been updated to clarify that GenderNexus provides referral letters for gender-affirming care, not direct medical referrals.

When Beth Clawson’s 11-year-old daughter Kirin began taking puberty blockers last year, her doctors gave her an arm implant, a small insert in her tricep about the length of a key.

An implant, the doctors reasoned, would provide gender-affirming therapy for up to 12 months without the need for refills. The implant would allow Kirin to safely continue treatment if her ability to get care in Indiana was withdrawn.

They were preparing for a reason. Last April, Gov. Eric Holcomb signed a bill banning Indiana doctors from administering gender-affirming hormone care, including puberty blockers and hormone replacement therapy (HRT), to anyone under the age of 18.

Puberty blockers are a reversible form of hormone therapy often prescribed to children with gender dysphoria that pause the production of sex hormones in children beginning puberty, around age 10 or 11. Puberty blockers do not permanently stop the body from producing sex hormones, and research by the New England Journal of Medicine found transgender youth on puberty blockers and HRT reported decreased symptoms of anxiety and depression and improved satisfaction with their life and appearance.

Yet critics contend hormone therapy is too severe of a medical transition for minors to be deciding for themselves — hormone therapy for minors requires parental consent — and note that puberty blockers can weaken bone density, though these effects are also not permanent.

An injunction was granted against Indiana’s youth gender-affirming therapy ban last June, a month before it was set to take effect, but providers like Clawson's were still on guard. The injunction could be lifted. The law could still be revived.

On Feb. 28, it was; the U.S. Seventh Circuit Court of Appeals in Chicago issued a stay on the injunction, allowing the law to take effect immediately.

Overnight, children on puberty blockers and HRT lost medication access. Sudden withdrawal from testosterone and estrogen can cause side effects including hot flashes, headaches and mood swings.

“And these are kids who needed appointments the day after the injunction was lifted,” Beth Clawson said. “So people were scrambling to find very few spaces for quite a few kids.”

In addition to gutting youth gender-affirming services in Indiana, the newly enforced ban barred doctors from making referrals to out-of-state providers, leaving transgender kids and their families on their own to find and continue care in other states.

In the wake of the ban, similar to those seeking abortions in states that have banned the procedure, families are turning out-of-state to find care for their children.

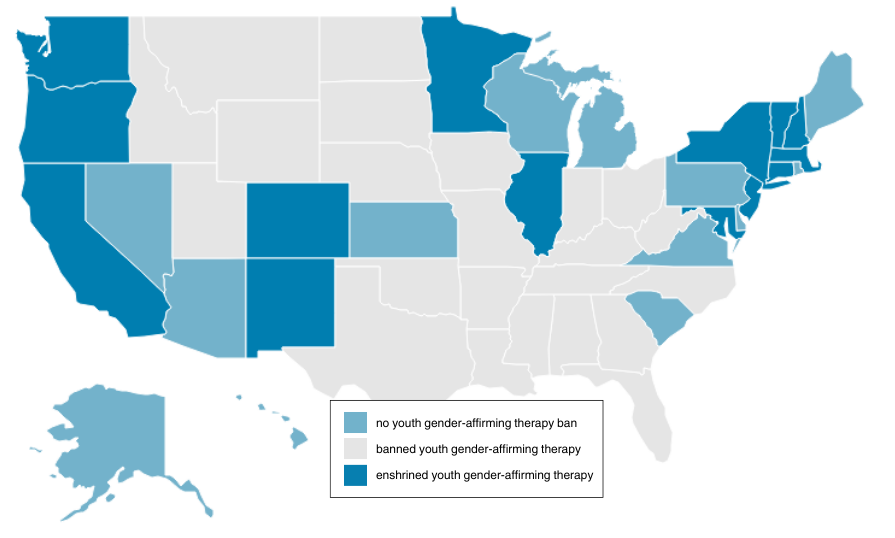

It’s not easy. Ohio, Kentucky, and 21 other states also banned youth gender-affirming therapy, resulting in clinics in the few neighboring states that do offer care, including Illinois and Michigan, having more than yearlong waitlists.

Yet, since the law took effect, trans activist groups across the state have also seen a rise in interest and attendance. They have become informal resource hubs for connecting people with doctors, transportation and travel expenses for those crossing state lines to find care.

‘Everything just stopped’

Within 36 hours of the Seventh Circuit Court staying the injunction on youth gender-affirming therapy, Emma Vosicky, executive director of the Indianapolis-based group GenderNexus, received 17 messages from parents of transgender kids.

“They were terrified about what was going to occur, and what it meant for their child,” Vosicky said. “All of them hit a brick wall. If they had a prescription that needed to be filled, if they needed a new prescription – everything just stopped.”

GenderNexus provides both support groups and care coordination services, like supportive referral letters for gender-affirming care and gender and name changes in the legal system. But since the ban, Vosicky says, GenderNexus has effectively become a “triage” resource for families, helping them understand exactly what the law says and providing information regarding medical resources doctors in Indiana aren't allowed to mention.

“Even if a physician knows that there’s medical care out there that can help their patient, they can’t say that under our law,” Vosicky said. “It smacks of 'The Handmaid’s Tale,' that people have to travel to states where they can actually get medical support.”

Connecting families with out-of-state care

Anti-LGBTQ+ legislation has been on the rise in state legislatures across the country in recent years, with 2023 seeing a record number of anti-LGBTQ+ legislation being introduced, according to the American Civil Liberties Union. Critics note these bills are largely peddled by influential Christian conservative groups like the Alliance Defending Freedom, which the Southern Poverty Law Center defines as a hate group. Groups like the ADF have also promoted bills that seek to ban transgender females from female sports teams and require teachers to inform parents if their child came out as gay or transgender.

Another battle: Bloomington family fights for transgender daughter amid bill banning her from girls' sports

Even before the gender-affirming therapy ban, Beth Clawson, Kirin’s mom, had been getting involved with Protect Our People, a Bloomington-based LGBTQ+ advocacy group.

“It reached a point a few years ago where we couldn’t just observe anymore,” Clawson said.

But since February, Protect Our People has become part of a statewide network that connects transgender youth with gender-affirming care across state lines, providing referrals, hotel costs and even transportation through a volunteer network of drivers.

“We’re working on donations to be able to afford gas cards, money for hotels, money for food and travel, and we have a network of people who volunteer their time and their cars to take people to the care,” Clawson said.

Clawson says POP has also been working with groups across the state like GenderNexus and Y’all for All, an Indiana nonprofit that provides grant funding to transgender and gender-diverse individuals seeking medical access.

Challenges to out-of-state care

Accessing care isn’t as simple as getting to the next state. Clinics in states that do offer gender-affirming care are often concentrated in distant metro areas, including Chicago, Grand Rapids, Detroit and Minneapolis. Some clinics only administer HRT to those 16 or older, and few offer telehealth options for follow-up appointments.

Endocrinologists in these states are also overbooked and underpaid, due to low industry pay rates. Laws like Indiana's have also strained pediatric endocrinology providers as masses of out-of-state clientele from Indiana, Kentucky, Ohio and Missouri seek appointments.

“People are just really scrambling,” Clawson said.

Vosicky notes the Seventh Circuit Court has only stayed the injunction, meaning the ban could still be reversed in the future. But she worries in that time, pediatric endocrinologists and transgender kids and their families will permanently move away.

“I’ve had to watch some amazing people move out-of-state,” Vosicky said. “The state now has a reputation for this.”

'Open season on queer kids'

Even as these groups focus on providing medical support for transgender kids out-of-state, advocates stress the importance of support groups and solidarity within Indiana.

Kristina Inskeep, a parent of a transgender child and the founder of the Indianapolis-based support group Gender Expansive Kids and Company (GEKCO), said since the injunction was lifted, she’s seen a significant increase in the number of families attending group meetings.

“We’ve lost a lot of sleep over this crisis,” Inskeep said. “Families are outraged, and they’re hurting.”

Melanie Davis, a founding member of POP, said even as these groups work to provide care access, she worries about the psychological damage to transgender youth seeing discriminatory laws and hate speech levied against them. She points to the recent death of Nex Benedict, a non-binary Native American teen from Oklahoma who was hospitalized after being physically harassed at school. Benedict's death was ruled suicide. The district attorney announced no charges would be filed in the case, sparking outrage from allies who say Benedict’s hospitalization and death were the direct result of a hate crime.

“It’s open season on queer kids,” Davis said. “That’s what that says.”

Inskeep said childhood transitioning is a deeply personal and difficult journey for many kids and families and should not be determined by legislators — especially those without a relevant medical background.

“We parents don’t enter into this lightly, this is not something that happens overnight,” Inskeep said. “We consult with other parents, we read books, we read articles. It’s outrageous to me that legislators who have no experience with this legislate health care for other people’s kids. It’s beyond sad to witness.”

Clawson says the political environment in Indiana has made her and her family consider moving out of state. But as she works with POP and other advocacy groups to connect transgender children to healthcare, she feels it's vital to continue the fight here.

“We worked hard to find a place that we love and create this community,” Clawson said. “And we don’t want them to take that away from us.”

Reach Brian Rosenzweig at brian@heraldt.com.

This article originally appeared on The Herald-Times: Indiana's trans youth care ban drives families out-of-state