Lexington County leads SC in loss of farmland. A new study recommends expanded protections

Lexington County is losing its farmland faster than anywhere else in South Carolina, and a new study suggests additional protections might be needed to safeguard the county’s agricultural land amid already spirited debate over rapid growth and development in the area.

The pilot study looking at Lexington was part of American Farmland Trust’s Palmetto 2040 project, which follows up on previous research indicating that “South Carolina is at very high risk for future farmland loss, with over 280,000 acres of farmland converted to non-agricultural uses between 2001 and 2016, giving the Palmetto State the eighth highest ‘threat score’ in the nation.

“Lexington County led the state in farmland conversion, with over 29,000 acres converted to non-agricultural uses,” the study report said.

The trust, founded in 1980 to advocate for the country’s farms and ranches, offered initial 2040 projections for the state in 2022, detailing that if current development trends continue unabated, South Carolina stands to lose the equivalent of 3,600 farms, $239 million in farm output and 5,900 jobs, based on county averages.

“The biggest takeaway for me is that we came up with a path, an optimal path for future conservation in Lexington County,” said Billy Van Pelt, national director of strategic initiatives and senior advisor for American Farmland Trust.

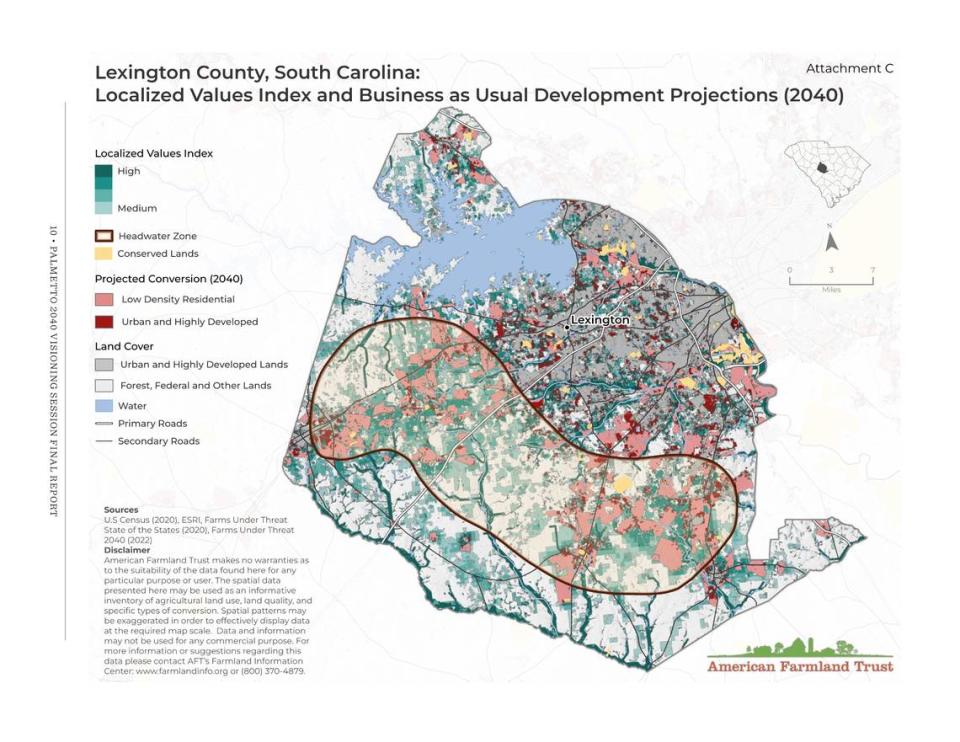

Coming out of the pilot study, which modeled how Lexington County would look in the future under different development scenarios and pulled together input from local stakeholders, the trust offered a few different recommendations, including one big one that Van Pelt said could help the county maintain the county’s valuable farmland: a headwaters protection zone.

As drawn in the report, the protection zone would cut a wide swath through southern Lexington County, stretching nearly all the way from the county’s western border to its eastern border and encompassing the majority of the rural areas south of Lake Murray and the urban centers of West Columbia, Cayce and the town of Lexington.

“These are the best soils in the county. These are the best waters in the county,” Van Pelt said. “This is the part of the county that’s under the greatest threat, ag and forest. So let’s focus our conservation efforts here.”

A map included with the report projecting what the area would look like in 2040 if “business as usual” policies continue unchecked shows a large amount of low-density residential development moving into the headwaters protection zone, much of it following along U.S. 1, U.S. 321 and S.C. 302, key highways connecting the county’s rural south to more urban areas in the north.

Addressing the loss of farmland in areas such as this could be crucial to supporting the agricultural industry and the overall economy, both in Lexington and throughout South Carolina.

“We do see some trends that have us concerned here in Lexington County and other places where we’re losing farmland to development or other purposes,” South Carolina Commissioner of Agriculture Hugh Weathers told a meeting of the Lexington Chamber in March, explaining why the American Farmland Trust study was important.

Bill Stangler, who works as the Congaree Riverkeeper to advocate for the health of local waterways, said the proposed headwaters protections are a good place to start, for both the health of local agriculture and local ecology.

“Riparian buffers and wetlands, they filter pollutants out of water, they restore flood water, which reduces flooding, which reduces the impacts on communities, they provide critical habitat for numerous species,” he said.

Stangler added that Lexington County’s existing ordinance calling for riparian buffers — strips of trees, shrubs or other vegetation planted alongside waterways to protect them — is pretty good. But now is a good time to push for additional protections, as the county is actively considering how it wants to grow heading into the future.

“I think you are hearing from a lot of folks, and this isn’t necessarily just true of Lexington County, but it is happening all around the Midlands,” he said. “People are saying, ‘Hey, I moved out here because I wanted this rural kind of character in my community, I didn’t want to be stuck in this urban center. And now it’s come to me.’”

Eva Moore, communications director for the South Carolina Department of Agriculture, noted that decisions that will impact the land within the proposed protection zone will have to come at the local level. The report does make some specific proposals for action at the state level, which she said is already happening.

“Several of the proposals in the study are about incentivizing the protection of farmland, like offering some carrots, offering some mechanisms for people to be able to preserve farmland and to want to preserve farmland,” Moore said, adding that the state recently added a fund offering grants to purchase and preserve farmland to the S.C. Conservation Bank and that the South Carolina Farm Bureau has a new private land trust offering conservation easements for much the same purpose.

The county government hasn’t yet taken any specific action related to the study, but Lexington County Council Chair Beth Carrigg said it should be added to the agenda soon for discussion.

Protecting farmland has been on council’s mind already, with the body having moved in January to expand an agricultural overlay district that already encompassed a large part of southern Lexington County. That district now covers not just lands surrounding Pelion, Swansea and Gaston, but lands surrounding Gilbert and Summit and lands to the east of Batesburg-Leesville as well.

Council also tightened restrictions within the district, lowering the maximum number of dwellings allowed from between two and four for most street types to between one and three and increasing the buffer surrounding agricultural operations from 30 feet to 75 feet.

“As we continue to work on our growth and management, I would love to see more farming creep up out there, and I know that they need incentives to successfully navigate that process,” Carrigg said. “I’m not a farmer. So I have to obviously work with them and see what their needs are and what we as a county can do to support that.”