Legal fight over Jim Thorpe’s body could be over

A federal appeals court ruled on Thursday that the Pennsylvania town of Jim Thorpe can keep the body of the late sports legend, probably ending a dispute over athlete’s final resting place.

The 3rd U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals said that Thorpe’s body should remain in the town, calling a U.S. District Judge’s prior ruling in the case “absurd.”

The current legal fight involves a decision in 1953 by Thorpe’s late third wife, Patricia, to sell his remains just after his death to two towns in eastern Pennsylvania called Mauch Chunk and East Mauch Chunk.

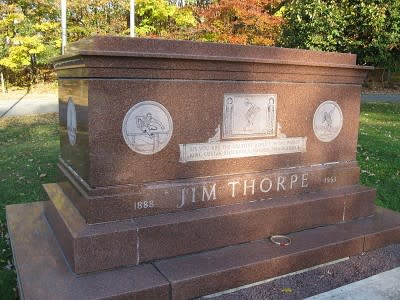

Patricia Thorpe claimed the body the night before a traditional Sac and Fox burial ceremony could take place in Oklahoma. Thorpe’s remains were sold on the condition that the towns combine, call themselves “Jim Thorpe,” and erect a monument to Thorpe.

Part of Thorpe’s lineal family and the Sac and Fox Nation of Oklahoma were suing the town of Jim Thorpe, Pennsylvania, asking that his body be returned to Oklahoma under terms of the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act of 1990.

The plaintiffs claimed the Thorpe memorial falls under the definition of a museum receiving federal funds and his remains are, in fact, artifacts that should be returned to his lineal descendants in Oklahoma.

U.S. District Judge Richard Caputo had earlier determined that Thorpe’s body should be sent back to Oklahoma under the terms of the act of Congress.

“Thorpe’s remains are located in their final resting place and have not been disturbed,” Chief Judge Theodore McKee said in his ruling today. “We find that applying (the repatriation law) to Thorpe’s burial in the borough is such a clearly absurd result and so contrary to Congress’s intent to protect Native American burial sites that the borough cannot be held to the requirements imposed on a museum under these circumstances.”

Link: Read the ruling

“NAGPRA was intended as a shield against further injustices to Native Americans,” McKee said. “It was not intended to be wielded as a sword to settle familial disputes within Native American families.”

Thorpe stunned the world by winning the pentathlon and decathlon in the 1912 Stockholm Olympics by a huge margin over two favorites. The news made global headlines, and Thorpe received a hero’s welcome in New York City.

Little known outside the United States, Thorpe was a college football star at Carlisle Institute in central Pennsylvania and was already a legend there by 1911 after he scored all his team’s points in a win over Harvard.

Thorpe’s parents were both part-Native American at a time when some Native Americans didn’t have the right to vote in elections. In fact, until a congressional act in 1924, about one-third of Native Americans living in the United States weren’t considered citizens and were not eligible to vote.

Thorpe grew up in the Sac and Fox Nation in what became Oklahoma. He had a multicultural background, since his parents were Catholic and Native American.

Thorpe fell on tough financial times after his sports career ended, and he died in California in 1953 at the age of 64, just two years after his story was made into a movie starring Burt Lancaster.

It was just after Thorpe’s death in 1953 that two legal battles took root that restored his Olympic glory and led to the current fight over his burial place.

In a long legal fight that eventually saw the U.S. Congress side with the Thorpe family, the IOC partially restored Thorpe’s name to the Olympic record books in 1982. (His original gold medals were stolen from museums after Thorpe returned them to the IOC.)

It turned out that Thorpe’s biographers discovered he never violated the amateur rules of the Olympics in the first place, since the claim about Thorpe’s pro baseball career was filed well past a reporting deadline in 1913.

Ironically, as the court case continued over Thorpe, his body rests in a mausoleum that contains soil from his home in Oklahoma and dirt sent from the former Olympic stadium in Stockholm, Sweden.

For now, the plaintiff’s final option would be a Supreme Court appeal. There was no comment from the plaintiffs as of Thursday afternoon.

Recent Stories on Constitution Daily

Malala Yousafzai receives Liberty Medal in Philadelphia

Constitution Check: When the Supreme Court acts silently, what does it mean to say?

Constitution Check: Will a brief 1972 ruling stop the same-sex marriage movement?