How the Legacy of a Reconstruction-Era Massacre Shapes Voting Rights Today

Shauna Sias, 48, has lived in Opelousas, Louisiana, almost her entire life. And thanks to her father, a civil rights advocate who battled racial segregation in the Deep South, she’s always known about the massacre that shattered the small Louisiana city during Reconstruction.

Over the course of around two weeks beginning on Sept. 28, 1868, white men in Opelousas murdered as many as 250 people, most of them Black Americans. The vigilantes’ goal was to suppress Black voter turnout ahead of the November presidential election.

The Opelousas Massacre was one of the deadliest episodes of racist violence during the country’s second founding, and its deeper aim — to limit Black voting strength — mirrors political conflicts plaguing Louisiana more than 150 years later.

“It feels like we’re in the same fight today,” Sias, an organizer, told Capital B. “We aren’t getting massacred the way we were in 1868, but we’re still getting massacred — we’re still fighting for the same equality. It’s just a different century.”

Consider Louisiana’s years-long redistricting clash.

In January, Republican Gov. Jeff Landry signed into law a congressional map that gives the state a second majority-Black district. Previously, Black residents could elect their preferred candidate in only one district, even though Louisiana is 33% Black. Days after the new map was enacted, a group of white voters filed a lawsuit challenging it. They hope to bring back the lines that diminished the influence of their Black fellow Americans.

“Nothing, really, has changed,” Sharlene Sinegal-DeCuir, a history professor at Xavier University of Louisiana, explained to Capital B, reflecting on the loud echoes between the past and our present. “I don’t think that this history has gone away — at all. Black people here continue to struggle to have their voices heard.”

Of course, disputes over maps stretch beyond Louisiana. For instance, the U.S. Supreme Court will soon decide whether it’s OK for South Carolina Republicans to use a racially discriminatory congressional map if the lines are drawn to secure a partisan objective. And the high court has ordered the 2024 elections in Galveston County, Texas, to be conducted under a map that had been deemed “mean-spirited” because it carves the diverse county into all majority-white districts.

Yet Louisiana feels especially noteworthy. It was one of the most progressive states during Reconstruction: Its 1868 constitutional convention extended the franchise to Black men, and other provisions demanded the integration of public schools. Today, however, Louisiana is associated with rigid conservatism, and it ranks near the very bottom on the issue of fair representation.

Read on for the stories of some of the Black organizers on the front lines of Louisiana’s present-day fight for racial equality.

The mother standing in her power

Baton Rouge native Ashley Shelton, the president and founder of the nonprofit Power Coalition for Equity and Justice, relishes the city’s towering civil rights history.

In 2003, she worked on the 50th anniversary of the Baton Rouge Bus Boycott, the first action of its kind during the mid-century struggle for Black liberation. It served as a model for the more well-known Montgomery Bus Boycott led by Martin Luther King Jr. in 1955.

Shelton, 47, explained that these events, designed to force white city leaders to integrate local buses, shape her reason for being: helping Black Louisianans own their power.

“Our work is about building power for disenfranchised communities,” she told Capital B. “We often ask: How do we help people understand what power means to them? It’s the power to change their circumstances and address problems in their communities.”

One of the best ways for Black Louisianans to change their circumstances? Through the vote — through electing someone who has their interests at heart and can confront problems such as the dire state of criminal justice in the state. This fact is why protecting the effectiveness of Black votes is so central to Shelton’s organization, which was a plaintiff in the redistricting case.

“If you codify into law that I can’t even elect a candidate of choice, elect a candidate who could change the policies that are harming Black and brown people in our state, then you’re saying that I’m actually a second-class citizen, because I can’t change my circumstances,” she said. “I can’t put anybody in government who’s going to make a difference in my life or in the lives of my children.”

It’s hardly lost on Shelton that Black Louisianans are locked in many of the same political battles today as they were in the 1960s or 1860s. The notion, she stressed, that racial discrimination is no longer an issue — that “we made it” — simply because Barack Obama was in the White House is ridiculous.

And yet, even in the face of sobering racial realities, she remains ferociously optimistic about the future of the country’s burgeoning multiracial democracy.

“I’m as angry as anyone else about everything that’s happening right now. But I also see opportunity here,” she said, “opportunity for us to stand in our power as Black voters and choose leaders who are going to do the work of the people.”

The trailblazer leading the “New Southern Strategy”

New Orleans resident Alanah Odoms isn’t only informed by history — the 42-year-old herself has made history as the first Black woman to lead the ACLU of Louisiana, which was established in 1956.

Odoms said that she and her colleagues connect their present-day civil rights work — including their efforts to rein in the menace of racist policing and protect the sanctity of the ballot box — to the past so that people can understand the evolution of systemic oppression.

Call it the New Southern Strategy. It’s something like an inversion of the Republican Party’s plot in the latter half of the 20th century to grow its political power among white voters below the Mason-Dixon line by stoking their resentment of civil rights gains.

“I like to think of the work we and others do as the New Southern Strategy, making sure that voting rights are protected in the Deep South,” she told Capital B. “What we’ve seen over the past decade is the repeal of pieces of the Voting Rights Act, and this white supremacist force become stronger and stronger.”

Through 2013’s Shelby County v. Holder, the U.S. Supreme Court defanged Section 5 of the Voting Rights Act, which had mandated that states with histories of racial discrimination receive federal approval before changing their voting policies. Without this backstop, individual citizens and civil rights groups have had to increasingly depend on Section 2 to challenge racial discrimination in voting.

This use of the provision is poised for a Supreme Court showdown, where several Republican-nominated justices seem eager to gut it.

Despite this bleak outlook, Odoms is energized by the fact that Louisiana’s recent redistricting victory — her organization represented plaintiffs in the case — offers a chance for the American South to reject the white power structure.

She’s lived in New Orleans for 16 years, and one thing she’s learned during this time is that numbers are crucial. The state has had only five Black people represent it in Congress since Reconstruction, and stronger Black representation can bring vulnerable communities greater access to key resources, including roads, schools, and hospitals.

“We often talk about policy issues in terms of narrative stories, which are very important. But, really, we’re talking about the number of seats in the House and the Senate. We’re talking about numbers,” said Odoms. “We have an opportunity to talk about not only the narrative of equality — but also the importance of a system that produces numbers that actually serve the people.”

The Opelousas native leaning into history

Shauna Sias said that it baffles her when people want to erase the history of racism in the U.S. when that history is still incredibly fresh.

She remembers walking hand in hand with her father and mother in the early 1980s into an Opelousas restaurant where Black Americans weren’t welcome. The staff were so furious that a Black family had dared enter their establishment that they loaded up her father’s food with red pepper. They wanted him to take his wife and young daughter and get out. But he ate it all anyway.

This moment made a huge impression on Sias, and it’s partly why a lot of her activism focuses on teaching children about the past.

“I sometimes joke that I don’t fool with adults. What I mean is that, with adults, it’s like trying to bend a grown tree. You can’t do it. But with a young tree, you can influence how it grows,” she told Capital B. “And I use that metaphor simply to say that we need to let these younger generations know about past struggles.”

To that end, Sias has helped to develop a wide-ranging curriculum intended to nourish children both intellectually and emotionally.

“We teach them about the importance of voting rights and knowing about people such as Fannie Lou Hamer and Michelle Obama and people in the local community. We still have people here in Opelousas who went through integration. We have to remind everyone that they’re still alive,” Sias explained.

On top of zooming in on history, she added, “we empower children by teaching them how to build healthy relationships.”

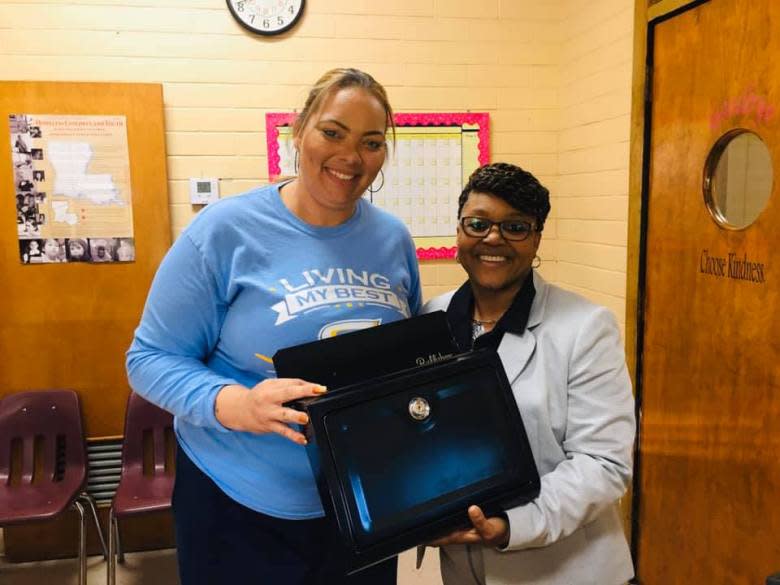

In 2019, Sias created the “bully box,” a locked box where students can leave notes about any bullying they’re experiencing or observing on campus, at home, or in their neighborhoods. It’s a simple and secure way to let children know that someone cares about them.

At a moment when Republican lawmakers across the U.S. are laying siege to classroom instruction about race and identity, she feels that access to honest and high-quality education is one of the most important civil rights issues of our day.

“We need to concentrate on getting the tools to build our own table,” Sias argued, “to build an education system where no one can tell us what to teach or what not to teach in our schools.”

The post How the Legacy of a Reconstruction-Era Massacre Shapes Voting Rights Today appeared first on Capital B News.