Learning to live in Trump House

In trying to make sense of Donald Trump’s victory Tuesday, it helps to take the long view. A good place to start is with the tumult of the 1960s. Trump’s stunning election is the unintended — but actually unsurprising — consequence of a great and essentially positive revolution in society and politics that is still far from over. His rise to power carries great risks, but it is possible that his time in office will be part of a turbulent, sometimes traumatic process that we can still use to work toward a better future.

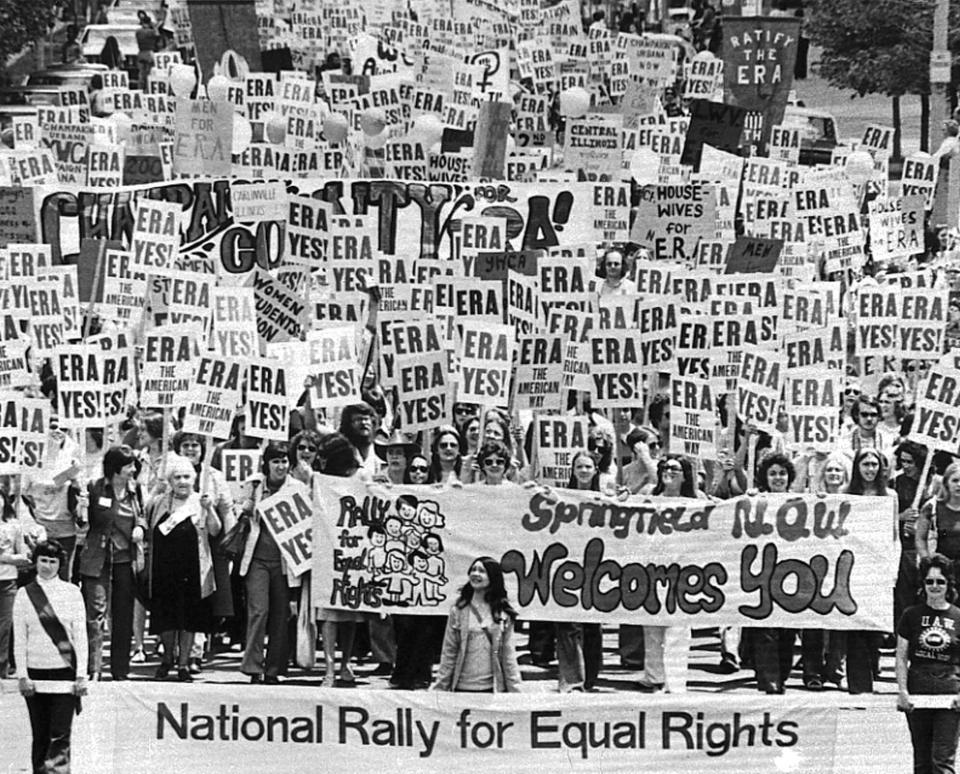

When the 1960s began, most Americans were disempowered or disenfranchised. Women were in many ways second-class citizens, relegated to the kitchen and the important — but poorly paid — roles of nursing and teaching. Blacks in the south were stripped of the vote and denied equal opportunity in jobs and housing almost everywhere. Similarly oppressed were Hispanics and Native Americans. The country was run by roughly a third of its population — the white males who had the money and the power. Even among white males, Jews and Catholics were still, in the early 1960s, scrambling to enter bastions long held by Protestants.

The 1960s changed that. By law, equal rights were recognized for women and minorities. Anti-discrimination laws swept away state-sanctioned prejudice and even offered minorities a leg up through affirmative action. Freedom was on the march — sexual freedom, freedom of choice, personal freedoms of all kinds. To a degree never before experienced by most Americans, you could express yourself in any way you wanted; the law permitted it and society encouraged it. To use an academic term, people were given “agency” — control over their own lives.

This was a wondrous, revolutionary happening. But it came at a cost, one worth remembering as we ponder Trump’s appeal. The white males who by and large had run the show for the first two centuries of America’s existence lost a degree of power, certainly at the lower end of the economic scale. Some welcomed the role of the new man — the chance to be close to children and meet their spouses on equal terms — but just as many or more resented the loss of unquestioned authority and standing. (Yesterday, they voted overwhelmingly for Trump.) The widening gap between rich and poor ground salt in the wounds of the men who had lost their good union factory jobs to robots or (less often) foreigners.

The hope of freedom is that free markets will lift all boats and, more broadly, that a free people will be better able to self-govern. That dream is based in the 18th century enlightenment ideal that mankind is essentially rational and capable of self-governance, and that the hidden-hand laws of supply and demand will produce more prosperity for all. The reality is more sobering. Recent experience and research in neurology and psychology have found what ancient Greek playwrights and Shakespeare knew all along: Reason is a thin veneer over deeper and sometimes base impulses —love and passion, yes, but also jealousy and anger. And as we have repeatedly learned through cycles of boom and bust, complete economic freedom can be a license for exploitative greed.

Technology greatly magnified personal freedom — for better, by liberating self-expression, and for worse, by magnifying and unleashing our darker sides. The Internet and Twitter made everyone editors of their own self-promoting publications. Social media brought us together — while at the same time deeply dividing us. Facebook and other sites allowed social tribes to form and re-form and find like-minded “friends” — while banding together against all enemies, real and imagined. The impact of the World Wide Web on truth was, to put it mildly, not what one might have hoped. In theory, in a true marketplace of ideas, the best ideas triumph and falsehood falls by the wayside. In practice, the Internet has harbored an open sewer of lies and calumny. “News,” sometimes accurate, sometimes not, comes from your friends (or is randomly picked up while surfing the Net), not from long established TV networks or news organizations. Newspapers and broadcast networks had their biases, to be sure, but some attempt was made to check the facts. Objectivity on front pages may have been a pretense or an illusion, but there was at least some effort to be balanced and fair-minded. Those rules do not apply to whole categories of social media.

By empowering and freeing everyone, we have hardly created one big happy family. Rather, we seem to be prone to splitting into tribes, each with its own version of the truth. In political terms, it sometimes seemed we aimed for a modern liberal democracy — and ended up with warring feudal states out of the Middle Ages.

Or, to pick a more pedestrian but familiar and telling example, think of your (or your kids’) college dorm. A college dorm is like the cliché of hope over experience. Typically, with their almost mystic faith in diversity, college administrators will try to stack every dorm and, if possible, every rooming combination, with a veritable rainbow of skin colors and varied socioeconomic backgrounds. The hope is that all these different people will benefit from each other and at least learn how to get along. Kumbaya.

Such is the hope. Walk into the cafeteria or the dining room and you will usually see a less uplifting reality. There can be friendships across social barriers, of course, but they are not the norm. Usually, the jocks sit with the jocks, sometimes by team. The sorority girls sit with the sorority girls, sometimes sorting by looks. The nerds with the nerds, the stoners with the stoners, the loners alone, and so forth. The black table, a creation of the 1960s, may now have more hues of brown, but it still rarely welcomes whites.

This might be depressing development, but for one reassuring fact: The kids graduate. They move on (some with more alacrity than others) from the cliques and hookups and beer stands and late-night squalor of college to the responsibilities of real life. The college administrators are not wrong to embrace diversity and try to mix and match those rooming combinations. Most kids do learn something about getting along with, and learning to live with, people who are not quite like them. Those experiences can be surprisingly useful in later life.

But it takes time and maturity. So, too, for nations and peoples. Who, aside from some old diehards, wants to go back to the 1950s, when roughly two-thirds of all people lacked the privileges and opportunities of the other (white, male) one third? It took the violent turbulence of the 1960s to change the laws, and it will take decades more, including four or eight years of Donald Trump, to sort out the consequences of those social revolutions and the technological breakthroughs that magnify the effects.

To extend the analogy, you might say we have just been assigned to a big dorm called Trump House. Trump personifies a certain cultural adolescence — boasting and posturing to hide his insecurities. The bragging is odious, but the boys rarely are the creeps they seem to be, not in the long run. They grow up, often humbled and made more sympathetic by rejection and defeat. The good ones calm down, learn from their mistakes, control their fears and play the game. We are playing a very long game as nation, and need to be calmer and more humble about it.

A college dorm, of course, is a relatively “safe” place, where you are supposed to be able to make mistakes. The real world is decidedly unsafe. There is no margin for error for leaders with nuclear weapons. Presidential words have consequences. Public celebrities can have a shockingly big impact on ordinary life. Consider the recent survey, reported in the New York Times, that showed that more than 40 percent of teenage girls said that Trump “had affected the way they thought about their bodies”! But we can use Trump’s ascendancy as the occasion to have some of the conversations we have been avoiding about race, sex, and social class. Perhaps they can be informed by a more realistic view of our basic natures, whether learned for neuroscience or Sophocles. From genuine debates about our natures and our needs can a next generation of leaders emerge.

Evan Thomas is an author and journalist. His last book was “Being Nixon: A Man Divided.” (Random House, 2015). Evan is currently working on a biography of Sandra Day O’Connor.

_____

Related slideshows:

Protests after Donald Trump’s victory >>>

Newspapers around the world react to Donald Trump’s victory >>>

Tears and cheers as Donald Trump and Hillary Clinton supporters clash at the White House >>>

World reaction to Trump’s stunning victory >>>

Trump defeats Clinton in 2016 election >>>

Election Night in America! >>>

Americans go to the polls to elect the 45th president >>>

Hillary Clinton and Donald Trump hold final rallies on Election Day eve >>>

Donald Trump’s America, Part 2 >>>

Donald Trump inspires his own brand of fashion on the campaign trail >>>

Face-off: Documenting the expressive battle between Hillary Clinton and Donald Trump >>>

(Cover tile photo: Carlo Allegri/Reuters)