Lawmakers eye housing audit that says Utah needs 28K new homes a year to keep up with growth

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

The Capitol in Salt Lake City is pictured on Monday, May 6, 2024. (Photo by Spenser Heaps for Utah News Dispatch)

In November, a legislative audit warned “time was running short” for policymakers to tackle the state’s growing housing crisis, and auditors estimated Utah needs to see nearly 28,000 new housing units built a year to simply keep up with the state’s projected population growth.

Using models based on Wasatch Front cities’ and counties’ existing general plans, auditors estimated those communities could “begin to run out of space” for housing in just 20 years. Auditors also reported if there continues to be a focus on single-family housing rather than higher-density housing, that could mean a “recipe for trouble as Utah continues to grow.”

In their conclusion, legislative auditors called on Utah lawmakers to create a statewide strategic housing plan, noting there is “currently no state-level forecast of housing needs, or efforts to set statewide housing strategy or measure progress toward a common goal.”

A panel of lawmakers reviewed that audit last week — and took the first steps to follow legislative auditors’ recommendations. The Political Subdivisions Interim Committee on Wednesday unanimously voted to open a committee bill file to consider the audit’s recommendations.

Meanwhile, Steve Waldrip, Gov. Spencer Cox’s senior adviser for housing strategy and innovation, told lawmakers he and a team have begun working on drafting a proposed statewide plan — a draft of which he hopes legislators can consider ahead of the 2025 legislative session.

“We are creating that statewide housing plan, which we should have to present to this committee hopefully before the next legislative session,” Waldrip told the Political Subdivisions Interim Committee. “We’d like to have something we can present, get feedback from the committee (and) make sure we come up with something that we can get behind as a state and have some concrete action items.”

The legislative audit will likely inform several bills expected for the 2025 general session — what is sure to be another year of legislative action dealing with Utah’s worsening housing crisis.

The discussion comes after the Utah Legislature this year focused its energy on encouraging “free market” solutions by creating a new arsenal of tools cities and developers can use to pay for infrastructure or finance affordable housing developments, hoping to pave the way for more affordable, single-family “starter” homes across the state.

It remains to be seen how much of an impact this new slate of tools will have, given it will take time for projects to take shape and require the cooperation of both cities and developers.

It’s still early, but Utah Gov. Spencer Cox — who recently doubled down on his goal for Utah to build 35,000 new starter homes in five years — told reporters on Thursday during his monthly PBS Utah press conference “we do have several builders that have said, ‘We’re in,’” and he said some cities are already working to adopt some of the new project areas.

“We’re getting some yeses, which is hopeful,” Cox said.

As for the next legislative session, a proposed statewide plan and the audit’s other recommendations? The question, of course, remains: what will Utah lawmakers do?

The case for a statewide plan

Jake Dinsdale, an audit supervisor within the Legislative Auditor General’s Office, briefed the Political Subdivisions Interim Committee on the audit last Wednesday, telling lawmakers, “we see a need for some long-range strategic thinking” when it comes to housing.

“We understand there is a difference between what (the) government can reasonably do and the economic forces at play,” Dinsdale said. However, he added legislative auditors believe “that accelerating housing production is a strategic imperative for the state.”

The “primary problem facing our market,” he said, is a shortage of housing units relative to population growth.

“We believe the Legislature is well-positioned to establish that state level housing strategy, and we believe without an overarching, unifying perspective and goal, there could be some opportunities lost to time as we continue to grow and as development proceeds without some orientating purpose,” Dinsdale said.

He cited research from the University of Utah’s Kem C. Gardner Policy Institute that was included in the audit, which shows Utah is on track to see more than a million new households formed by the year 2060.

“That’s, for us, a staggering number,” Dinsdale said. “(It’s) something definitely to consider.”

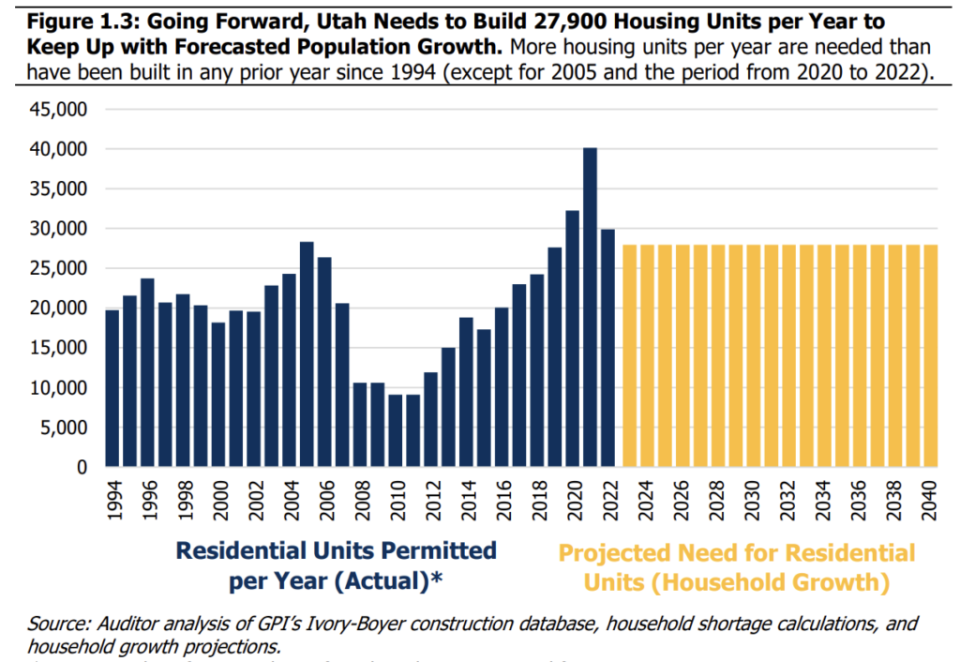

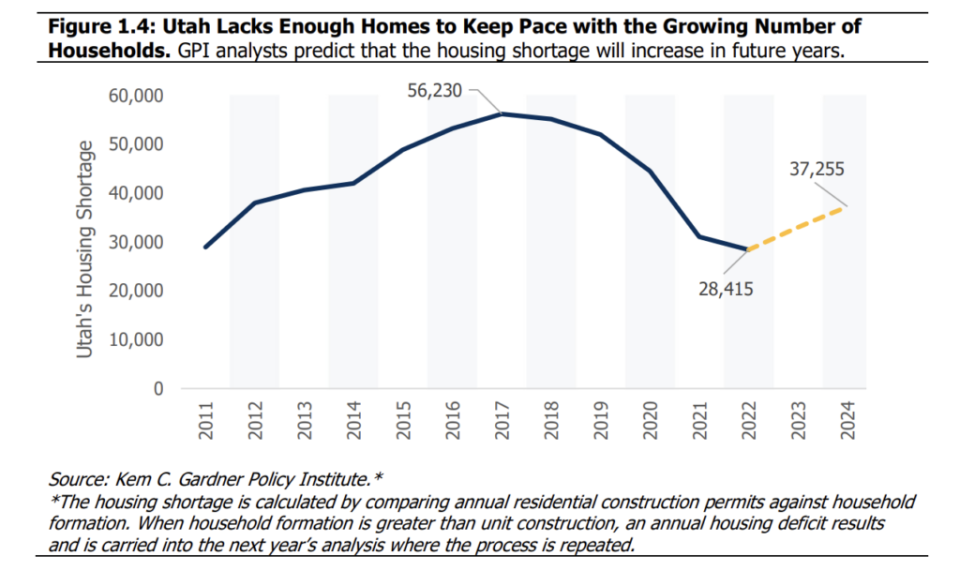

Auditors also compared residential units that have been permitted across the state per year since 1994 and estimated, based on those projections, Utah will need to build 27,900 housing units per year to keep up with forecasted population growth — something Dinsdale also called a “staggering number.”

Meanwhile, housing researchers at the Kem C. Gardner Policy Institute recently issued a report warning Utah’s housing shortage is projected to increase to over 37,000 units in 2024 — sure to aggravate the state’s ongoing affordability crisis.

While looking at zoning and what land is left for housing — particularly if single-family homes continue to be as pervasive as they are today — legislative auditors collaborated with the Wasatch Front Regional Council to run a hypothetical model on what would happen if cities and counties built out their current general plans

“When you run that model and build those houses according to our general plan maps, Salt Lake County, within that model’s assumptions, begins to approach its capacity for homes in 2042, and Davis County begins to approach its capacity in 2048,” Dinsdale said. “Again, (this is) not a crystal ball, but it does suggest there’s some conversations to be had about what path we are on relative to the growth that is forecasted coming to this state.”

He said the main reason this happens is because there’s a “lack of land-efficient housing options,” or “missing middle housing — things like townhomes, duplexes, triplexes … (homes) that are built on less land.”

Dinsdale acknowledged that some cities and counties have begun to adopt “station area” plans, or higher-density housing developments near transit stops and main thoroughfares, and if enough communities adopt those types of plans, “those counties no longer run out of space by 2050.”

“So this can have an impact on our trajectory,” he said, though he noted not all cities have adopted these transit-oriented developments in their general plans. “But to the extent that we can, it seems like it would be sensible to approve more areas like this so that we have more slack, more places to grow as people need housing options.”

Keeping all this in mind, Dinsdale said legislative auditors believe “Utah should adopt some state-level measures and targets for housing needs and construction.”

“We point out in the report that housing is a collective problem, but the regulatory decisions are made at the city and county level, and there is nothing orienting those in any unified direction,” he said. “The question being, is there a conductor in front of the orchestra?”

Policy changes on the table: Upzoning, benchmarks based on population growth

In addition to crafting a statewide plan, legislative auditors encouraged lawmakers to explore policy changes like tying land use requirements to projected population growth (as seen in states like California and Oregon) and to consider “upzoning,” or requiring cities to allow more homes to be built on less land (as seen in Minnesota, Pennsylvania or, more aggressively, New Zealand).

“As far as Utah goes, we have quite a light touch relative to some states that are legislating in this housing space,” Dinsdale said. He pointed to California, which has done what he called some “heavy programs” that use population growth forecasts to create targets for housing that they push down to cities.

Leah Blevins, an audit manager within the Legislative Auditor General’s Office, noted that they usually avoid comparing Utah to California because the two states are so different, but she said California has been dealing with acute housing issues for three decades now, “so we really wanted to look at it and see we can learn things from California but still implement it in a Utah way that works for us and avoid some missteps that have not helped.”

Dinsdale also pointed to Montana, which enacted legislation to allow apartments, accessory dwelling units and duplex construction in more areas. However, the laws are currently tied up in court after homeowners sued, with a judge blocking the laws from taking effect until the trial’s final outcome or the Montana Supreme Court rules differently.

“So we’ll see what happens there,” he said.

It’s possible the Utah Legislature could do something similar to Montana and change land use regulations more broadly to increase zoning density “on a wide scale throughout the state,” Dinsdale said, but pointing to Montana he added, “There’s pros and cons to that approach.”

The Legislature could also consider linking population growth benchmarks to existing programs, like the state’s requirements that cities create moderate income housing plans and report back to the state on their implementation.

In recent years, Dinsdale said some “great bills” have gone forward to encourage development around transit areas, but efforts haven’t been coordinated under a larger statewide vision.

“Where are we? Are we happy with where we are, are we on the right trajectory, or are we playing a good game but we’re still going to fall a mile short of the goal?” he said. “Those are the types of conversations that we do not see currently reflected in some of the great areas that are underway.”

Statewide planning

Waldrip, while telling lawmakers he and a team are starting to work on drafting a plan for the Legislature to consider, said Utah has historically relied on the market to “take care of market-rate housing plans.”

But now, given the state’s problems with housing, he said “we have to be a little more thoughtful, more aggressive.”

One challenge, Waldrip said, is Utah has several different types of housing markets, from the rural to urban, to the luxury backcountry.

“The housing market on the Wasatch Front is not the same as Park City, as Washington County, as Moab, and as Santaquin,” he said. “We just have very different needs in different parts of our communities, so we’re going to address that as we go through that process.”

Waldrip said Utah’s Commission on Housing Affordability is also studying the issue, including improving the state’s data collection so it has a more well-rounded understanding of the issue.

“We hope that by the end of this year we have a much better picture of what we’re facing in our state and how we can best attack it,” Waldrip said.

He added Utah isn’t alone; states across the nation are grappling with housing. He said the National Governors Association has a task force where “every three weeks we get on a call with executive housing departments from across the country and share ideas.”

“We’re all asking the same questions,” he said. “(It) doesn’t matter what color the state is, everyone’s got the same problems.”

Sen. Mike McKell, R-Spanish Fork, chairman of the Political Subdivisions Interim Committee, told Waldrip the committee “would love to look at any type of interim bill that you bring before us.”

Waldrip said Sen. Lincoln Fillmore and Rep. Stephen Whyte — sponsors of the 2023 set of housing bills — are likely to again open a “suit of four to six bills that will be needed to tackle all of these issues.”

Rep. Paul Cutler motioned to open a committee bill file to consider the recommendations for the legislative audit and to coordinate efforts with Whyte and Fillmore. The motion passed unanimously.

The post Lawmakers eye housing audit that says Utah needs 28K new homes a year to keep up with growth appeared first on Utah News Dispatch.