Why Starmer’s promise of growth risks falling on deaf ears

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Sir Keir Starmer drew on the words of a previous Labour leader as he laid out his vision for the country in 2021.

“A fair society will lead to a more prosperous economy,” he said.

“It’s not the choice of one or the other, as the Conservatives would have you believe. We either have both or we have neither. Harold Wilson once said that the Labour Party is a moral crusade or it is nothing – he was right.”

Three years on and many on the Left of the party are questioning whether their leader still believes in that equation.

Instead of focusing on redistribution, equality and an interventionist state – goals that would doubtless have been recognised by Wilson in Downing Street more than half a century ago – Starmer has a new mantra: “Growth, growth, growth”.

As the party stands on the cusp of power, thoughts of how to share out the spoils of economic expansion are taking second place to the question of whether it can be delivered in the first place.

Labour has been clear that it plans to fight the next election on the economy, and – to the fury of trade unions and activists who claim the party has capitulated to “corporate interests” – it is embracing bosses’ input on how to get there.

In private meetings, leaders have been brutally honest with shadow chancellor Rachel Reeves and deputy leader Angela Rayner about the potential pitfalls.

“The worry is that there’s a reductionist approach to economic growth. To focus on productivity as the only lens for growth seems old-fashioned, what about access to jobs? We can’t define good jobs on the basis of the top 2.5pc,” says Allen Simpson, a former Barclays banker who has been having regular meetings with Labour in his capacity as deputy chief executive of trade body UKHospitality.

He has already told Labour that zero-hours contracts can be in an employee’s interest and must not be banned, helping convince the party to abandon a policy championed by its trade union donors.

“People like me, who left their hometown and moved to a city, their prism of what success looks like is not the same as most,” says Simpson.

“Is social fairness the same as social mobility? No, not in all cases. Even if you make it so anyone of talent can become a CEO, someone still has to work for them. The question is how you make life fairer for those people. The danger always is focusing too much on social mobility and not social fairness.”

Having been a Labour candidate himself in his hometown of Maidstone back in 2015, when he took a month off at Barclays to knock on doors and fight for his seat, Simpson has thought long and hard about where economic traps could be hidden.

“The discussion [going on with Labour right now] is whether productivity is too reductive a measure of growth,” he says.

“It’s much more expensive to run a business in a community than in an industrial estate. Fiscal policy in the UK disincentivises communities.”

Such conversations are set to ramp up over the coming months, as the economy increasingly emerges as the key battleground between Labour and the Tories and politicians comb the business community for words of wisdom.

It’s the right tack – a former Tory donor who has now decided to bankroll Labour instead says he believes that Reeves “gets it” because “she understands that the priority is growth”.

Yet what so far seems most remarkable about the upcoming election contest is how many similarities there are between Labour and the Conservatives’ approaches to the economy.

Reeves has committed to the same fiscal rules as Jeremy Hunt. “That is going to tie their hands quite considerably,” says George Moran, economist at Nomura.

Labour has not opposed Hunt’s two National Insurance tax cuts, announced in the Autumn Statement and the Budget, but Reeves has heavily criticised Hunt’s aim of scrapping the tax altogether as an “unfunded pledge”.

When it comes to Labour’s own tax proposals, it plans to introduce VAT on private school fees and tighten the screws on non-doms. Reeves says she will not make further increases to corporation tax.

None of these ideas will bring in substantial revenue, meaning Labour’s focus is likely to be on structural reforms that are more realistic and less expensive, says Moran.

It is Labour’s proposals on planning reform where business leaders feel the party has an edge.

Starmer has promised to “bulldoze” the planning system and build 300,000 homes a year. This target is exactly the same as the Tories’, but there are two key differences with what Labour is proposing.

Firstly, Starmer says he wants to build on parts of the green belt, which could potentially unlock huge swathes of land.

Secondly, Labour has much more capacity to drive through its changes because its voters are not concentrated in the Nimby heartlands of the South East.

“Among economists, there’s quite a strong consensus that the planning rules are holding back growth. The main barrier [to reform] has been Nimbyism. This is a particular challenge for the Conservatives because a lot of their voters don’t want to have new construction projects in their backyard,” says Moran.

Labour will not face the same hurdles as Housing Secretary Michael Gove, whose own efforts were hijacked by a backbench rebellion that managed to extract a promise for housing targets to be dramatically watered down.

Planning reform is not just about building more homes, but also infrastructure, says Nick King, managing director of Henham Strategy and a former government adviser.

“Certainly a lot of the people I talk to in the development industry are concerned that there has been a poor approach from the Government in recent months and years and Labour are going to try and sort it out,” he says.

Last week was crucial for both sides, as Rishi Sunak hoped to use a series of economic updates to back his claims that he’s turning the economy around.

Although the Bank of England voted to keep interest rates on hold on Thursday, official data on Friday confirmed that the UK has shaken off last year’s small technical recession, defined as two consecutive quarters of falling gross domestic product (GDP).

Reeves wasted no time trying to counter the claims, arguing early in the week that the Government was “gaslighting” the public on the matter. The Tories said in response that Labour has “no plan”.

Real detail on Labour’s proposals is still lacking, says King.

Starmer and Reeves are wary of having policy ideas cannibalised by the Conservatives, as happened with their proposals to introduce an energy windfall tax and scrap non-dom tax exemptions.

One focal point is likely to be investment, says Moran. Reeves has said her fiscal rules will allow room for borrowing to invest, providing that it will pay for itself with the additional growth that it creates. This could open the door to more spending on R&D and infrastructure, says Moran.

It is also possible that in time, if the economic situation improves, Labour could revive some form of its abandoned flagship pledge to invest £28bn a year in green energy projects.

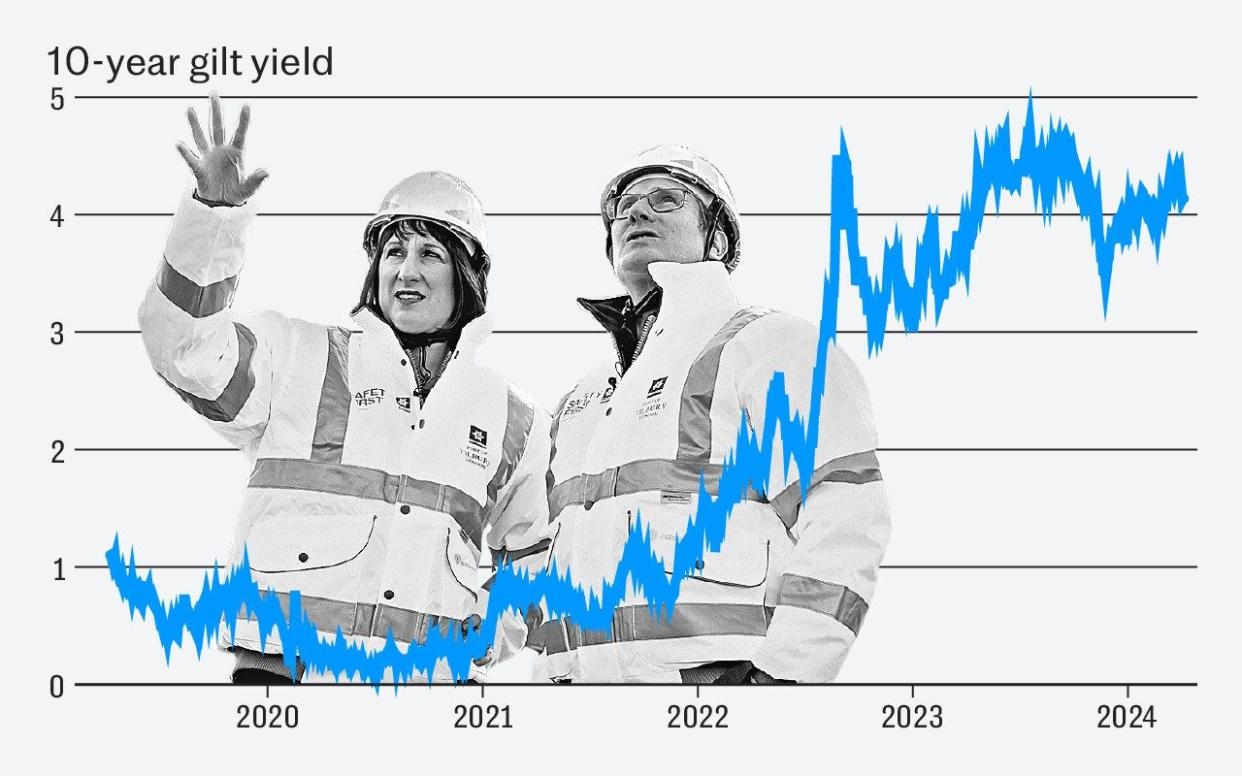

Starmer about-turned on this policy in February, as soaring high borrowing costs on government debt made the borrowing unviable.

“If the economic situation turns back, I think they would return to a preference for more green spending,” says Moran.

Everything will hinge on falling borrowing costs and fiscal headroom.

Yet many voters have lost interest in the political mudslinging between Right and Left following years of empty promises on economic growth (Liz Truss also promised “growth, growth, growth” during her short stint as prime minister).

One third of Britons do not believe that a booming economy would make any difference to their lives, according to a Public First poll published last month.

James Frayne, director of the policy research agency, warned that the Conservatives have told the public for years that they have the power to solve “practically every problem from ugly buildings to unhealthy living to the North-South divide – while magically raising economic growth”.

Fed up with outlandish promises, the public wants change. A YouGov poll on Thursday found that Labour had secured its biggest lead in the polls since the Truss era, with the party 30 points ahead of the Tories.

For businesses, a key difference between the two parties is Labour’s continued emphasis on stability.

Reeves argues that after the turmoil of the last few years, “stability is change”. The rhetoric and focus on long-term decision-making is resonating with businesses, says Nick Faith, director of WPI Strategy, a public affairs company.

But for executives trying to cosy up to Labour, polls may matter more than policy.

“I think businesses are probably positioning towards Labour more because they have a strong suspicion that Labour is going to be the next party in power,” says Moran.

“They want to have a voice in the room, therefore they’re approaching them now. It’s probably not all about whether Labour are particularly more business-friendly than the Conservatives are likely to be.”

Yet there are corners of the City where loyal Conservative backers are still whispering their concerns to anyone who will listen. As one investor was overheard saying at a recent business conference: “It’s bad now – wait till the other lot get in”.

Those on the left of Starmer’s party may fear that he has given up on Labour’s moral crusade. The country as a whole, though, is likely to need more persuasion that he won’t end up dancing to the same old tune.