You know that weird outer space radio signal? It's probably not aliens

By now you may have heard rumors about the recent detection of what's been described as a "strong signal," possibly sent out by an advanced form of alien life in a star system 94 light-years away.

Pretty exciting, right?

Well, before you go pack your bags and wait for the aliens to come along and pick you up, there are a few things you should know.

SEE ALSO: Check out this bright spot on one of Saturn's rings

The strong radio signal, detected by astronomers using a telescope in Russia, was actually heard in May 2015.

It's certainly a cool finding, but it's also nothing close to a confirmation of intelligent life out in the universe.

SETI Institute senior astronomer Seth Shostak thinks that the interest around this particular signal is probably "public-generated rather than science-generated," he told Mashable in an interview.

Many scientists "assumed from the very beginning that it's [the signal is] not very likely to be the real deal," Shostak said.

The 2015 signal and its potential significance was first reported on August 27 by Paul Gilster, who runs the Centauri Dreams blog, after he caught wind of an email going around among scientists about the possible SETI signal.

Researchers who documented the signal suggest that it comes from a part of the sky that harbors HD 164595, a sunlike star orbited by at least one Neptune-sized planet. The researchers were intrigued enough by this signal, Gilster wrote, that they are calling for "permanent monitoring" of the star.

Observations turning up empty

Image: SETI

For its part, the SETI Institute checked out the star with its Allen Telescope Array, a telescope used for many of these hunts before.

The telescope scanned the skies on August 28 and 29 searching for the signal, but it found nothing, Shostak said.

It's also definitely possible that the signal came from something far more benign than aliens.

The scientists who made the detection in 2015 concluded that the signal may have come from HD 164595. However, it could actually be coming from something else entirely.

For one thing, the radio telescope used to detect the signal made use of a receiver with a very "wide bandwidth," Shostak said on the SETI website, which makes it difficult to narrow down exactly how the signal was produced.

And other scientists agree with Shoshtak.

"Because the receivers used were making broadband measurements, there's really nothing about this 'signal' that would distinguish it from a natural radio transient (stellar flare, active galactic nucleus, microlensing of a background source, etc.)," SETI-focused astronomer Eric Korpela, wrote in a forum post about the signal.

"There's also nothing that could distinguish it from a satellite passing through the telescope field of view. All in all, it's relatively uninteresting from a SETI standpoint."

It's also possible that the signal isn't even space-based, Shostak said, instead coming from aircraft radar or another form of ground-based interference.

And the Special Astrophysical Observatory of the Russian Academy of Science seems to agree with the other scientists' decidedly skeptical assessments.

According to a translation of a statement released Tuesday, the academy suggests that the signal is "of terrestrial origin."

But... Aliens?

According to Shostak, if the signal were sent out by aliens trying to get in touch with us, it would have taken a crazy amount of energy to signal Earth in this way.

On the one hand, the civilization may have decided to broadcast its signal out in many directions, which would take 100 billion billion watts, Shostak said.

"That’s hundreds of times more energy than all the sunlight falling on Earth, and would obviously require power sources far beyond any we have," he added.

Another possibility is that the aliens targeted Earth, which would use less power, but it would still need more than a trillion watts, "comparable to the total energy consumption of all humankind," Shostak said.

"Both scenarios require an effort far, far beyond what we ourselves could do, and it’s hard to understand why anyone would want to target our solar system with a strong signal," he wrote.

"This star system is so far away they won’t have yet picked up any TV or radar that would tell them that we’re here."

Shostak also said that it's a little weird that the scientists who heard the signal waited until now, more than a year after the signal was heard, to contact scientists hunting for SETI signals around the world.

"According to both practice and protocol, if a signal seems to be of deliberate and extraterrestrial origin, one of the first things to do is to get others to attempt confirming observations," Shostak said in the SETI post.

"That was not done in this case."

Because the scientists were late to report, it might be more difficult to find the signal again, if it is still out there lurking in the universe.

A history of 'wow' signals

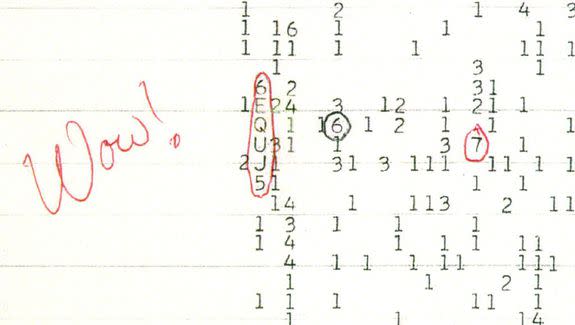

Image: Big ear/NAAPO/wikimedia

This isn't the first, nor will it be the last radio signal that gets members of the public and scientists alike excited.

SETI scientists pick up some kind of signal once every 10 seconds or so, but most of those can be ruled out as extraterrestrials pretty easily, Shostak said.

However, about once every decade, scientists pick up something that gets them really excited.

In 1977, a scientist picked up a signal so strong in a bit of data that he wrote "wow" in the margins of the paper showing it.

Further observations of the part of the sky where that signal came from turned up empty.

Shostak also remembers a moment in 1997 when scientists at SETI thought they may have found a real signal. The director of the institute even asked Shostak to come into the office from home after his colleagues saw the signal, but it turned out that a piece of equipment was offline, and the scientists were just picking up interference.

While Shostak does think it's unlikely that the newest signal to make a fuss was from some kind of alien civilization, he doesn't want to write off the idea of looking into it.

"You've got to check these things out, because it's easy enough to say, 'well, it's probably not real,' but if you've got that attitude, you'll never find anything," Shostak said.