Be a killer, be a king: The education of Donald Trump

During one of the dips in the roller-coaster ride that is Donald Trump’s life — in the midst of a bankruptcy drama, somewhere between the glittery opening of Trump Tower and the circus-like mania of this presidential campaign — the man himself admitted, briefly, to a moment or two of doubt.

“My father was right,” he told an acquaintance back then. “I should have stayed in Brooklyn.”

It is a telling comment, invoking as it does the two propelling forces of Trump’s life: besting his father, and getting himself across the river to Manhattan. To understand the man who is expected to accept the Republican nomination for president on Thursday night requires understanding those twin threads: the need to outdo his father while also seeking his approval; the determination to impress moneyed New Yorkers while also claiming not to care what anyone thinks.

“The answer for every question about him really, no matter what the question is, is ‘dominance’, the need to dominate,” Gwenda Blair, author of “The Trumps: Three Generations of Builders and a Presidential Candidate” said in an interview with Yahoo News. “Everything is focused on that, that’s his whole MO, and it all goes back to his dad, and to getting out of the outer boroughs.”

Harry Hurt III, author of “Lost Tycoon,” one of the first biographies of Trump, agrees. (His book, published in 1992 was just re-released via a Kickstarter campaign because the original publisher declined to risk a lawsuit from Trump by bringing it out again.) “It all goes back to his father. Since he was a child, he’s been vying for his father’s attention and everything else in his disturbed existence is rooted in the crazy need to prove he can outdo his father.”

This prism, they say, is the key to deciphering the presumptive nominee. (The Trump campaign did not return requests for an interview with the candidate for this article.) It explains Trump’s need to win, his seemingly racist, misogynistic and victimized worldview. And his sensitivity to insults and slights — the mark of someone who never felt fully accepted by the powers that be in the world he aspired to join. And it comes as close as anything to predicting Trump’s future — from the internal dynamics of his family to the raison d’être of his potential presidency.

*******

Before Trump’s father, there was his grandfather. Friedrich Trump was just 16 when he left a goodbye note for his mother in Germany in 1885 and booked passage in steerage to New York. He did not want to be a barber, as he had been trained to be back home. He was, Blair wrote, “infected by the dream of instant wealth.”

After a few years in Queens, Friedrich headed west, where there was money to be made. He bought restaurants in Seattle and then in the Yukon, which provided not only meals to the miners, but also women. A decade later, he took his accumulated wealth (about $350,000 in today’s dollars) and tried to return home and reclaim his citizenship in Germany, but was banned because his departure years earlier was considered draft dodging. So he sailed back to Queens, with his fortune and a new bride, where he bought more real estate (land and houses this time, not brothels) and raised a family.

His son, Frederick Christ Trump (the middle name was his mother’s maiden name, not a religious statement), was just 13 years old when Friedrich died, a victim of the 1918 influenza epidemic. Two years later, that son (known as Fred) and his widowed mother opened a construction business in Queens. Their first project was a neighbor’s garage. For years, Elizabeth Trump had to sign legal papers on Fred’s behalf, because he wasn’t old enough.

But Fred grew as his business did, and, like his father, he found a gold mine of a new frontier. For Friedrich that had meant looking west, for Fred it meant looking to the government. There was money to be made in the crises of the 20th century: The Great Depression created foreclosures to be bought up, the New Deal created subsidies for construction, the end of the war led to even more government investment in housing for returning soldiers. As Blair wrote, Fred Trump “joined the ranks of entrepreneurs who constitute one of the oldest fraternities in the Republic: multimillionaires who owe their fortunes to subsidies from a grateful government.”

Using Municipal Housing Authority loans, Fred built solid brick apartment complexes for middle-class families, with names like Shore Haven and Beach Haven, first in Brooklyn and then in Queens. He became one of the largest builders in the outer boroughs of New York City. With his growing wealth, he built a 23-room home in Jamaica Estates, with Tara-like columns out front. His children — Elizabeth, Fred Jr., Maryanne, Donald and Robert — watched TV on one of the very first sets in the neighborhood and were driven to school in one of their father’s chauffeured Cadillacs. The Trump children were required to work for spending money, and they all had summer jobs and year-round paper routes. But when it snowed, they were allowed to take the limo to deliver their papers.

From early childhood, Hurt wrote, Fred used to tell his boys “you are a killer … you are a king … you are a killer … you are a king…” As a result, he wrote, Donald came to believe that “he cannot be one without the other. As his father has pointed out over and over again, most people are weaklings. Only the strong survive. You have to be a killer if you want to be a king.”

At first Fred assumed that the king — and the heir to his business — would be his eldest son and namesake, Fred Jr., known as Freddy. But it became increasingly clear to everyone that Freddy was neither killer nor king. Instead, Blair wrote, he was a “sweet lightweight … loveable loser.” He tried his best, but his frantic scramble to please only seemed to infuriate his father. Mistakes — such as ordering new windows for a building when existing ones were still salvageable — earned him public tongue-lashings from his father. When Fred did something well, on the other hand, his sister Maryanne has said, his father pointedly said nothing at all.

Donald observed all this, and the message was to never be vulnerable. “He was the first Trump boy out there and I subconsciously watched his moves,” he said of his brother in a Playboy interview years later. “I saw people really taking advantage of Fred, and the lesson I learned was always to keep up my guard 100 percent.”

So began a most complex relationship with his father, who Trump spent decades trying to be — but also to be separate from, and better than.

“I used to fight back all the time,” he told journalist Marie Brenner in New York magazine. “My father respects me because I stood up to him.”

He “stood up” to everyone else around him, as well. He spitballed and bullied other students at school, snuck off to Manhattan to buy switchblades and stink bombs on weekends, acted like “a brat,” his sister, Maryanne told Tim O’Brien, author of “TrumpNation.” (O’Brien was sued by Trump, unsuccessfully, for suggesting he was worth far less than the billions he claimed.

It was all his way of getting attention from his father, those who study Trump agree. “Donald … did have his father’s irrepressible energy, which the old man believed was a genetic gift, and a streak of the devil, which the old man begrudgingly admired, as well,” Hurt wrote. “Where Freddy immediately cowered under Fred’s reprimands, Donald reacted by clamoring for more attention with incorrigible mischief.”

Or, as biographer Michael D’Antonio wrote in “The Truth About Trump” (the candidate hasn’t sued him, but once threatened to), “Trump is often ruled by the needy child who resides in his psyche and would rather get negative attention than be ignored.”

What it got him, at first, was three years in the New York Military Academy, a high school designed to both toughen and straighten out young men. He thrived at NYMA, Blair wrote, probably because “for the first time [he] was in a place that channeled competitiveness and aggression instead of tamping it down, a place where winning really mattered.”

His years there were followed by two at Fordham University and two more at the Wharton School at the University of Pennsylvania, an Ivy League business school, which his brother had reportedly unsuccessfully applied to. (His sister Maryanne told Blair that Donald got in after a meeting with an admissions officer who had been a high school friend of Freddy’s.) By the time he graduated in 1968, Freddy had moved to Florida to become an airline pilot; an alcoholic, he died in 1981 at the age of 42.

“How does anyone become the way they are?” Wayne Barrett wondered in an interview with Yahoo News. (One of the first New York reporters to write in depth about Trump during the 1970s, Barrett recently reissued his 1992 book “Trump, The Deals and the Downfall” with the new title “Trump: The Greatest Show on Earth: The Deals, the Downfall, the Reinvention.”) If Freddy had been “a more competitive guy, maybe Donald would have been less so,” Barrett said, “and that would have altered so many other pieces of his personality and we wouldn’t have the election we have today.”

******

When Donald was 8, his father was investigated by Congress over $4 million in windfall profits on money he took from the Municipal Housing program to build veterans’ housing, the source of his original fortune. When Donald was in college, Fred Sr. was investigated again about similar accusations that he took advantage of the spirit, if not the letter, of government-funded subsidies when building Trump Village (the only one of Fred’s developments to carry his own name.)

There were no charges filed in either case, but there were months of headlines about “real estate profiteering” and “milking the government.” And both times, Fred’s defense was essentially that “the system let him do it,” D’Antonio wrote. In his testimony, Fred even suggested that the lawmakers themselves were responsible for his greed because they created ways for him to take advantage.

In other words, he seemed to be saying, the system was rigged against him. It is a logic that might sound familiar to those who have heard Donald defend his four bankruptcies (“Basically, I’ve used the laws of the country to my advantage … just as many, many others on top of the business world have”) and his reliance on outsourcing labor (he is the one who knows how to fix the laws, he said during a Republican debate, because he’s spent so many years exploiting them.) And it is but one of many lessons that Donald learned from his father.

“The most important influence on me, growing up, was my father, Fred Trump,” Donald wrote in “The Art of the Deal,” the first of 20 books that carry his byline.

Among the other things Fred seems to have taught him:

Image is everything. In addition to famously changing how he described his heritage — from German to Swedish — to avoid offending his Jewish tenants during the Nazi era, Fred tweaked and burnished whenever possible. He always wore his signature custom-made suit and red tie, complete with gold collar pin and matching pocket square, even when not working. His son also wears suits and mostly red ties, and his casual wear usually includes a logo from some Trump property or campaign.

When Donald was still a toddler, Fred hired public relations man Howard Rubenstein to land him on a list of the best-dressed men in America in 1950 (along with Dwight Eisenhower and Phil Rizzuto) and to send out press releases about his life story, one that “parallels the fictional Horatio Alger saga about the boy who parlayed a shoestring into a business empire.”

“He saw that media generated respect, which generated financial success, which in turn generated media,” Blair wrote.

Never go bald. “That started with his father,” says a former employee who worked with both men. Fred never sported a comb-over, but he did perfect a “comb-back,” and had a habit of commenting on the hairlines of others. So did his son. A number of his biographers describe how he chastised Mark Etess, one of his top executives, for losing his hair. “The worst thing a man can do is go bald,” he reportedly said. “Never let yourself go bald.”

Keep your options open on matters of religion and politics. A registered Republican, Fred paid dues to Brooklyn’s two most powerful Democratic clubhouses, gave generously to Democratic candidates and bragged about his influence with them, including a claim that New York Mayor Abe Beame would do his bidding. Similarly, while a member of the Reformed Church in America led by Dr. Norman Vincent Peale, nationally famous as the author of “The Power of Positive Thinking,” Fred was also active in Jewish philanthropies. Many prominent real-estate developers in post-war New York City were Jewish, and it was often assumed that Fred Trump was as well.

No one mistakes Donald for being Jewish. But he has switched parties more than once, and has been known to cite religious texts in which he is not particularly fluent.

Toot your own horn. As a teenager, Donald accompanied his father to the ceremony that opened the Verrazano-Narrows Bridge. Standing with his dad, watching one politician after another give speeches, Donald’s attention was drawn to a man standing by himself, apparently unnoticed.

It was the 85-year-old designer of the bridge and Donald’s takeaway, as described years later to a New York Times reporter, was “if you let people treat you how they want, you’ll be made a fool. I realized then and there something I would never forget: I don’t want to be made anybody’s sucker.” Or, as he explained the same event to Tim O’Brien in “TrumpNation”: “You know, we live in a vicious world, and oftentimes if you don’t say it about yourself, nobody else is going to.”

But most of what Donald absorbed from his father was a desire to surpass him. In a classic Freudian sense, Donald seems to have taken his lifelong fight for his father’s approval and turned it into a need to prove himself better than Fred.

****

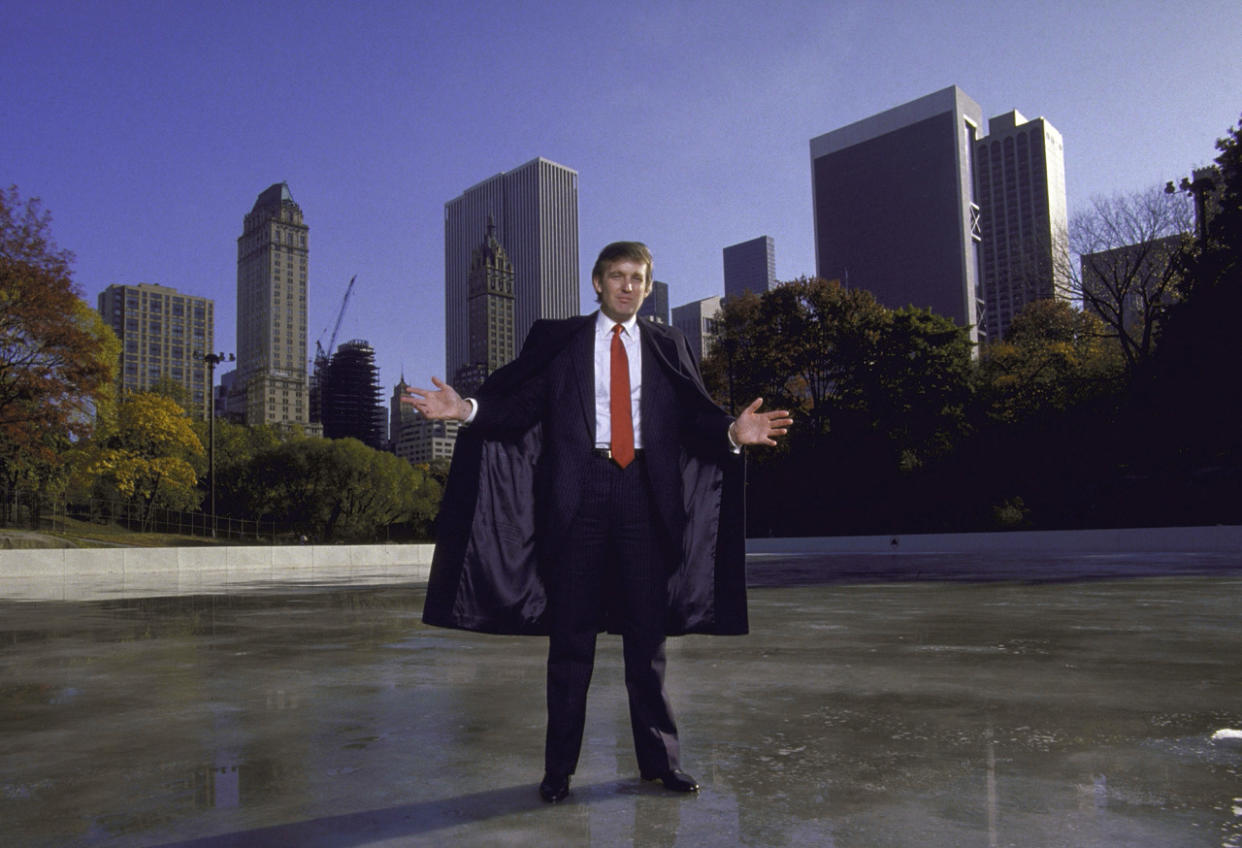

Besting his dad meant going the one place his father wouldn’t or couldn’t — across the river to Manhattan. It’s a story as old as the skyline itself: the ambitious young man looking at the glitter and the glow and wanting it for himself.

“It wasn’t his thing,” Donald said of Fred in an interview with Blair. “Manhattan just didn’t make sense to him. He was familiar with the pricing out in Brooklyn. Why pay thousands of dollars for a square foot of land in Manhattan when out there he paid 30 cents?”

It did, however, make sense to his son.

“Donald was constantly talking about changing the Manhattan skyline,” a former high school classmate told Hurt. And Donald’s senior-year roommate remembered: “He used to talk about his dad’s business, how he would use him as a role model but go one step further.”

As Donald told O’Brien, the Manhattan-sized opening Fred left “was the best thing that ever happened to me. If my father had come to Manhattan, he would have been successful and you probably wouldn’t be talking to me right now. You understand that? In a certain way, I would have been a son of a guy who made money. Making money in Brooklyn isn’t the same. It’s different.”

So Donald moved to Manhattan, starting out in a tiny apartment on East 75th Street, which he described as a penthouse even though it was on the 17th floor of a 21-story building. “Moving into that apartment was probably more exciting for me than moving 15 years later into the top three floors of Trump Tower, he wrote in “The Art of the Deal.” “I was a kid from Queens who worked in Brooklyn, and suddenly I had an apartment on the Upper East Side.”

For five years he commuted back to Brooklyn, to the shabby headquarters Fred maintained on Avenue Z, all Formica furniture and plastic plants, with a few towering wooden Indian sculptures that Fred collected. Donald parked his Cadillac convertible, with the DJT plates, next to his father’s Cadillac limo, with its FT1 plates, and looked for a first deal he could do on his own in Manhattan.

He found it at the Commodore Hotel, next to Grand Central Station, originally built by railroad magnate Commodore Vanderbilt but now a crumbling mess that was losing about $1 million a year and filled with rats big enough to kill the cats sent in to get rid of them. The city surrounding the hotel wasn’t in great financial shape either — this was 1974, the midst of a recession — and Fred disapproved of Donald taking over the property. “Buying the Commodore at a time when even the Chrysler Building is in receivership is like fighting for a seat on the Titanic,” Fred said.

But in spite of — or perhaps because of — his father’s reservations, Donald forged ahead. “The old man’s reaction only inflamed Donald’s desire to prove himself,” Hurt wrote. “It was not enough just to make a good deal for the Commodore. He had to make a great deal that would make his old man and everyone else take notice.”

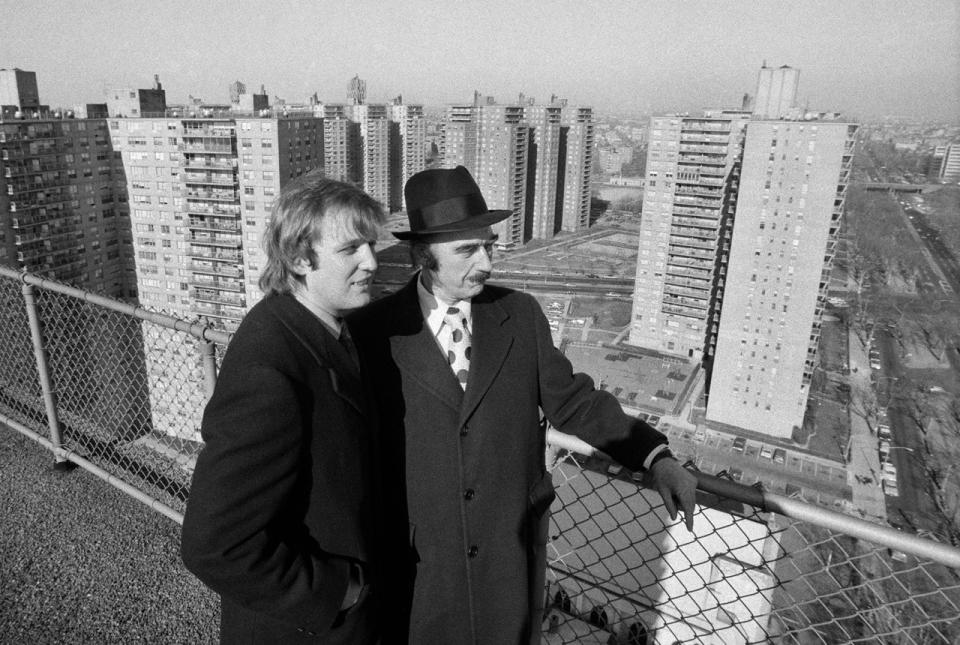

Donald did come up with a great deal, an elaborate plan that had the city buy the property and lease it back to the Trump Organization for 99 years with a significant tax abatement that would total more than $100 million. Donald used the New York City Urban Development Commission to fund this plan much as his father had used the MHA in postwar Brooklyn. And he also depended on his father’s connections in the Beame administration and, says Barrett, his father’s willingness to “sign the option. Penn Central wasn’t going to turn over the options to this 30-year-old kid.”

Barrett suggests that as much as Donald thought he was moving beyond his father, he was actually “a front for Fred. Mayor Abe Beame came out of the same club as Fred, his political associations with Fred were well known,” he says. “If they had made a deal this sweet with Fred Trump, who had weathered two scandals and was scarred by them, it would have looked like the worst kind of cronyism, the worst kind of political insider trading. It had to be done with a glamour boy like Donald, who could get the kind of copy he got, reviving midtown in the dark days of the city.”

But if Donald didn’t make the deal entirely on his own, he certainly designed the building his way. Partnering with Hyatt Hotels (the Commodore name would be changed to the Grand Hyatt) he wrapped a sleek mirrored-glass skin around the original bones of the building and created what architecture critic Paul Goldberger called “an out-of-towner’s vision of city life.” He also morphed the 26-story building into a 34-floor one, not by building any extra floors, but by renumbering the guest floors to start at 14. And he expanded the ballroom to the “largest in the city” by declaring it so, even when it was pointed out to him that there were larger ones elsewhere in town.

Blair wrote that at the opening party in 1980, guests “took the Grand Hyatt elevators to what they supposed to be the 34th floor, and they danced in what they believed to be the biggest ballroom in New York City. And if all that wasn’t quite so, they really didn’t care.”

With the Grand Hyatt a success, Donald moved on to build Trump Tower, also over his father’s skepticism. The design included 58 separate angles on the saw-tooth façade, but to Fred, “who had made his reputation and fortune putting up square buildings, [and] to whom extra corners meant extra leaks, the very idea of a saw-tooth building was incomprehensible,” Blair wrote. In “The Art of the Deal,” Donald quotes his father as saying, “Why don’t you forget about the damn glass. Give them four or five stories of it, and then use common brick for the rest? Nobody is going to look up anyway.”

Donald and his new wife, Ivana, moved into a three-story, 53-room apartment on the 66th through the 68th floors of Trump Tower (the building was actually only 58 stories high, but, ya know…) and Donald took to boasting that, at 80 feet long, “I have the largest living room in New York.” (By all accounts, he actually did.) His father, however, never lived in the apartment that Donald had set aside for him a few floors down, preferring to stay in Queens.

******

Trump Tower marked the final separation of father from son, a reversal of roles. What it did not mean, however, was that Donald had conquered Manhattan, at least not in the way he had set out to do from across the river. And since Manhattan in so many ways represented his ultimate victory as both a “killer” and a “king,” that is likely a shortcoming that continued to sting.

Through all his building, buying and especially his bankruptcies, Donald Trump never gained the approval of the social arbiters of the city. He bought (and lost) yachts, and sports teams, casinos, beauty pageants. He built (and leased his name to) dozens of buildings. He starred in a reality show. And still, as gossip columnist Liz Smith wrote in her autobiography, he was never “after all, popular with [his] betters — New York’s movers and shakers,” because, she said, “these threatened people looked down on new money that wasn’t their own.”

The wider world of power and influence snubbed him too. He often invited the Reagans to Mar-a-Lago, the Palm Beach estate he purchased and turned into a resort after he was rejected by the old-money Florida clubs, but they never visited. He responded by dissing the establishment back, calling them the “lucky sperm club,” in contrast to self-made men like himself, his father’s fortune aside. He predicted he would outlast them. (“In 50 years we will be the Rockefellers,” his first wife, Ivana, once said.) He decided he didn’t care what they thought. “In short, [he] did not want to fit in,” Blair writes. “Newer was better, more was more, and being noticed was always better than being one of the crowd.”

But the man-child who never completely got his father’s approval probably cared quite a lot. “Donald is actually the most insecure man I’ve ever met,” said Abe Wallach, who once served as head of acquisitions for the Trump Organization, in an article in which the New York Times tried and failed to find many people who consider themselves Trump’s real friends. “He has this constant need to fill a void inside. He used to do it with deals and sex. Now he does it with publicity.”

Fred Trump died in 1999 at the age of 93. At his funeral, his children and grandchildren eulogized the man and his life. When it was Donald’s turn to speak, he spoke about … Donald.

As described by Blair, who attended, he started by saying “it was ironic … that he had learned of his father’s death just moments after he’d finished reading a front-page story in the New York Times acknowledging the success of his biggest development, Trump Place.” Listing his grandest projects — the Grand Hyatt, Trump Tower, Trump Plaza, Trump Taj Mahal — he described his father as being “totally supportive” of every one. “In short,” Blair concludes, that funeral morning “did not belong to Fred Trump after all, it belonged to Donald.”

And now he is running for president. Those who have observed him all these years are not particularly surprised. All families are shaped by recurring dynamics across generations — some actively reject them, others actively embrace them, but all are defined by them.

In the Trump family paradigm, the patriarch sets a pace and waits to see which child catches or outruns him. So far, Barrett suggests, Ivanka seems to be winning, as her father “skips over Donald Jr., just like Fred Sr. father did to Freddy.” And Ivanka, true to history, is “positioning herself very strongly as the anti-Trump Trump, a purposeful contrast with her adored father,” wanting to be just like him, but very different too.

Trump, playing his role, responds by upping the stakes in the constant quest to prove himself a killer and a king. What more dramatic means to that end than to run for president of the United States?

Whether he could actually “achieve election to the most powerful job in the world was unclear” to Donald when he decided to run, Blair wrote. “But at the least, as he saw it, he would be the most stupendous, mind-blowing, and altogether amazing presidential candidate the world has ever seen.”