Can Kevin Young Make Poetry Matter Again?

On August 25, 1835, residents of New York City woke to the sound of newsboys howling about an astonishing discovery. According to The New York Sun, a British astronomer had discovered life on the moon. Using a giant telescope outfitted with an ingenious “hydro-oxygen” mechanism, the newspaper said, Sir John Herschel had “affirmatively settled” the question of whether the moon was inhabited.

The Sun narrated its account of Herschel’s discoveries over six days. Among the astronomer’s findings were “not less than thirty-eight species of forest trees,” horned bears, and beavers walking on two legs. On the fourth day, the paper reported the discovery of humanoid creatures with batlike wings and faces that were “a slight improvement upon that of the large orang outang.” On the sixth day, two more races of bat-men were described. One was larger than the first, “less dark in color, and in every respect an improved variety.” The other was more attractive still, “scarcely less lovely than the general representations of angels by the more imaginative schools of painters.”

Though Sir John Herschel was a real astronomer, the Sun’s account - published without his knowledge - was, of course, fake news. What came to be known as the Great Moon Hoax was intended as satire, but much like Orson Welles’s War of the Worlds broadcast a century later, the story was taken for truth. It was copied by other newspapers, translated into foreign languages, and debated by learned astronomical societies. Edgar Allan Poe called it “decidedly the greatest hit in the way of sensation - of merely popular sensation - ever made by any similar fiction either in America or in Europe.”

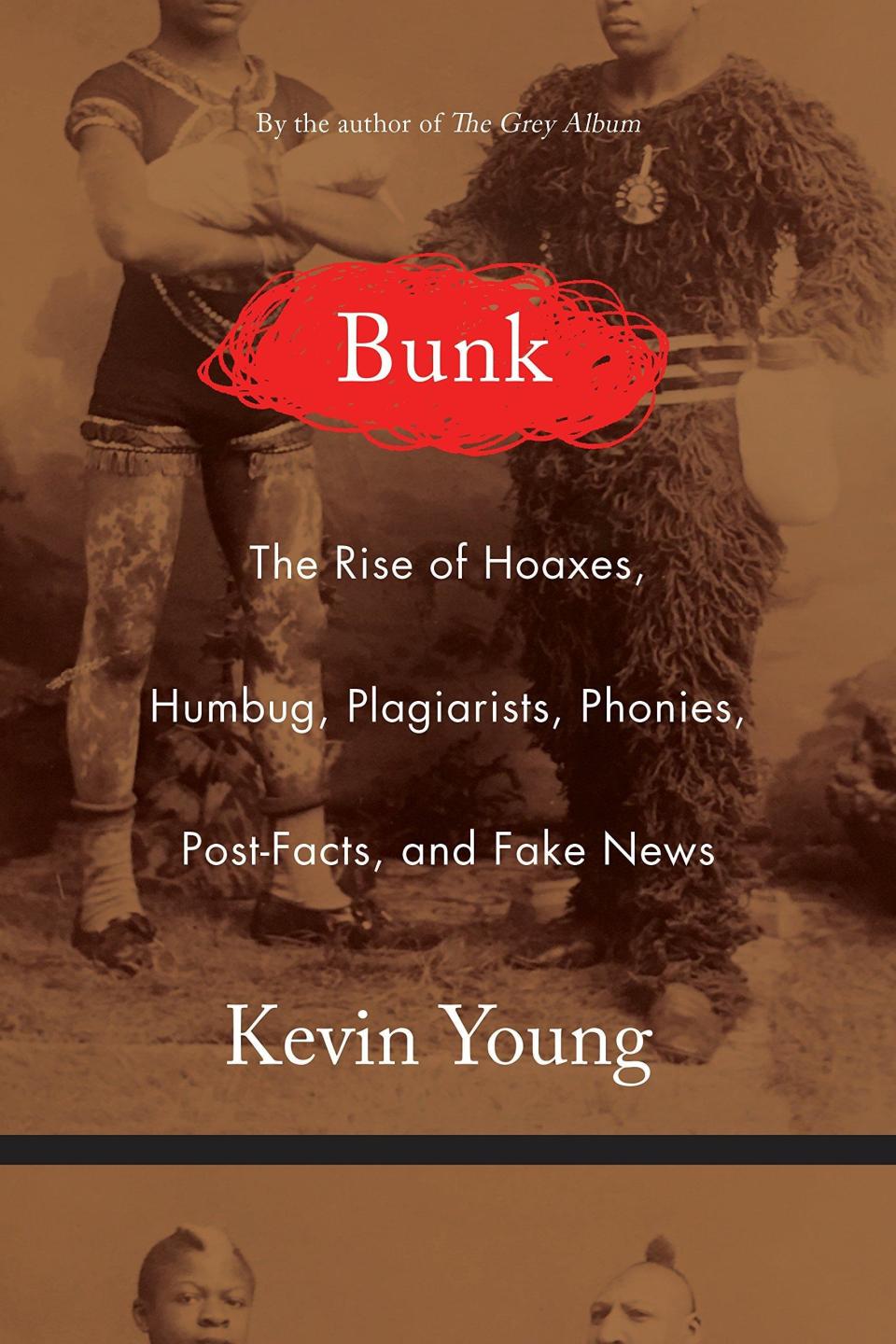

In his new book, Bunk, a cultural history of hoaxes in America, the poet Kevin Young argues that the popularity of the Sun’s story “owed much to its re-creating on the Moon what many white readers believed could be found at home.” With the hoax’s distinction of ethnic groupings among the bat-men, he says, “it is tempting to see the lunar humanoids as hierarchical in the ways white eugenicists characterized races on earth.” For Young, the implication of race at the center of what is sometimes described as America’s first great hoax is no accident. As he proposes near the end of Bunk, “You could go so far as to say that the hoax is racism’s native tongue.”

One afternoon this past summer, I met Young in the lobby of the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture in Harlem, which he has directed since 2016. It was a cloudless day, hot enough that I was sweating under my sport coat. Young, more intelligently, was wearing a plaid shirt rolled up to the elbows. On one arm he wore an Apple Watch, on the other a leather cuff.

Like Bunk, which was longlisted for the National Book Award two months before its publication, next week, Young has had his share of precocious success. He won an award from the American Academy of Poets during his freshman year at Harvard, and the poems he wrote to satisfy his thesis requirement were selected for publication in the National Poetry Series. Now forty-seven, he possesses a résumé that reads like a passport stamped on a Grand Tour of institutional high culture, with stops at Harvard, Stanford (a Stegner Fellowship), Brown (an MFA), Emory (a named professorship), and the Schomburg. He has published ten collections of his own poems, edited eight volumes of others’, and, with Bunk, written two massive volumes of nonfiction. Capping off this run, he has just taken over as the poetry editor of The New Yorker.

And yet while Young has accomplished enough, quickly enough, to suggest a man in a hurry, in person there is nothing rushed about his manner. As we headed out into the gentrified neighborhood around the Schomburg in search of a late lunch, he walked slowly, his weight on his heels, and took the time to point out local landmarks with the proprietary authority of an alderman.

After settling into a red banquette at a local African-French bistro, Young ordered a pork chop with haricots verts and a sweet fruit mocktail. He told me that he’d started thinking about Bunk before Donald Trump merited a joke at the White House Correspondents’ Dinner, let alone a desk in the Oval Office. He traces his interest in hoaxes to a boss he worked for in college who was later implicated in a number of scams. Back then, Young had shoulder-length dreadlocks and a goatee that traversed his upper chin in a narrow strip before unfurling in a rakish inverted plume. He maintained the dreads into his thirties - “It was important to have them and have them be a fact,” he said - but by 2001 they’d gotten “heavy on the head” and he lopped them off. (An inveterate collector, he still has them in a box somewhere.)

Young is well aware that everyone from Plato on has accused poets of being purveyors of eloquent deceit - “liars by profession,” as David Hume put it. But he insists that the hoax is the enemy of art. “People sometimes say hoaxes are about the blurry line between nonfiction and fiction. I just don’t think it’s a blurry line at all,” he said. Unlike hoaxers, artists promise their audience fair warning: “There’s a level of ‘Once upon a time’ or ‘In a galaxy far, far away’ that tells you I’m going to be telling you a story.” When that pact is broken, art stops and the hoax begins. “It means we’ve lost fiction,” he told me. “We’ve lost fruitful art.”

Coming soon after the election of a president who found his political footing with the help of a racist hoax about his predecessor, Bunk could hardly be more timely. But Young’s deeper argument is that we can’t escape race when we’re talking about hoaxes, because race itself - for all its implacable real-life effects - remains the most consequential hoax in American history. We cite this hoax explicitly every time we use the word Caucasian to mean “white”; the usage comes from a discredited eighteenth-century treatise that traced the palest and most beautiful of the world’s five races to the shores of the Black Sea. But we fall for it whenever we forget that at root, as Young writes, race is nothing other than “a fake thing pretending to be real.”

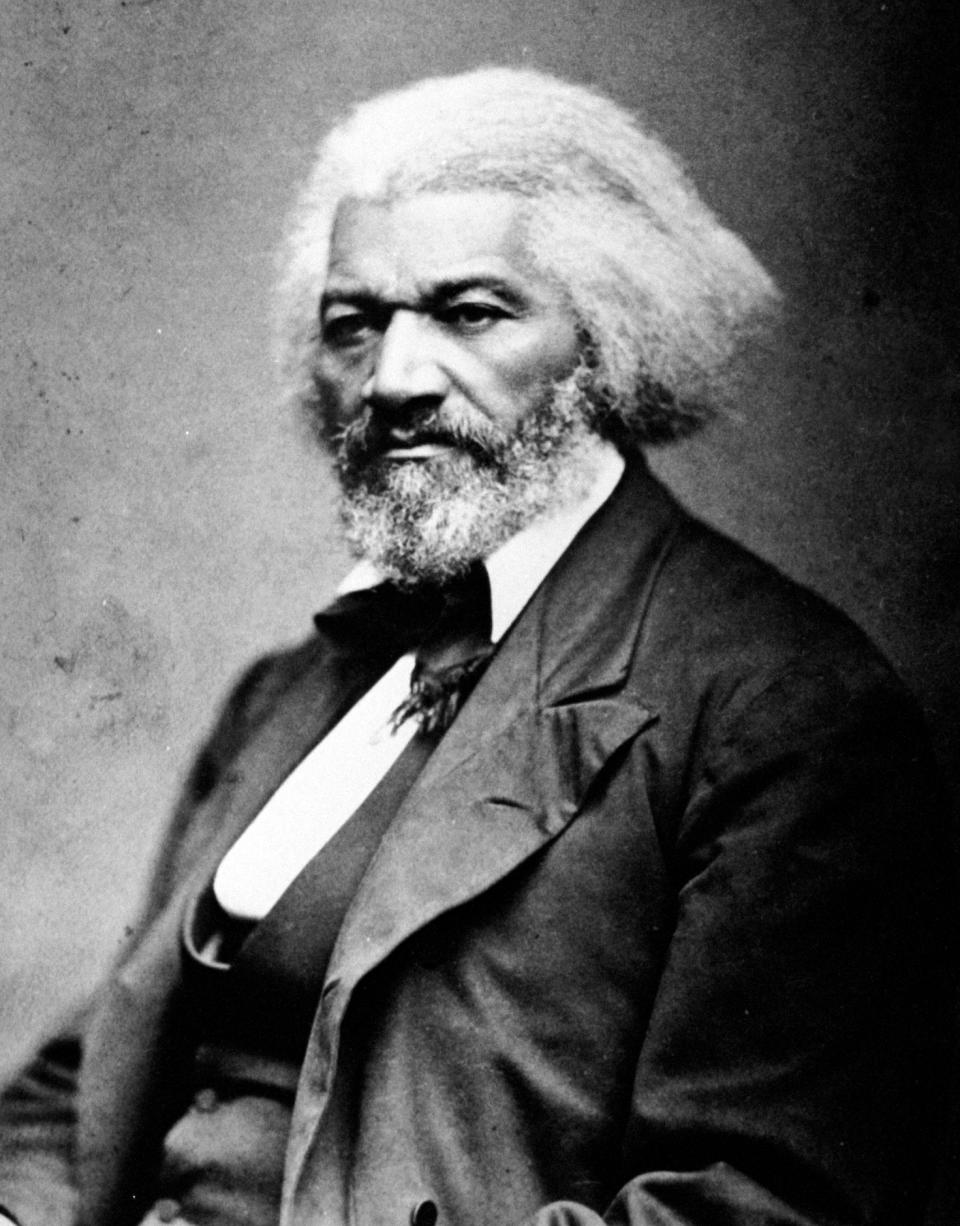

The race hoax was helped by a corollary that persisted in polite company even into the latter half of the twentieth century. As recently as 1963, Daniel Patrick Moynihan, a future Democratic senator, and Nathan Glazer, a distinguished sociologist, could write in their best-selling Beyond the Melting Pot that “the key to much in the Negro world” was that “the Negro is only an American and nothing else. He has no values and culture to guard and protect.” The notion of black culture as a nonentity, or at best an imitative agglomeration, is shocking now. But the so-called “myth of the Negro past” was an old and reliable accomplice for the long con of white supremacy. (In 1895, after the death of Frederick Douglass, The New York Times suggested that his exceptional accomplishments ought to be credited to the white race, since it was likely the “white blood” from his father - rumored to be a slave owner - that provided “the superior intelligence he manifested,” while his mother’s blackness “cost the world a genius.”)

With this myth squarely in his sights, Arturo Schomburg, a black historian from Puerto Rico, spent the early part of the twentieth century assembling what he called “vindicating evidences” to show its absurdity. He collected some ten thousand books, pamphlets, and art prints by black authors and artists, and in 1926 sold a substantial portion of that trove to the New York Public Library’s Division of Negro Literature, History and Prints in Harlem.

When Young showed me around the Schomburg, the center was nearing the end of a $22 million renovation. As we walked through an exhibition on Black Power, he took equal pride in the Black Panther posters and the center’s new video monitors. Like many poets, Young has an associative, allusive habit of mind, a frog-among-the-lily-pads tendency that has not always served his prose well. The New York Times complained that The Grey Album, his previous nonfiction book, was “wordy, hectoring and often glib.” But in conversation, his intellectual fluency, along with a talent for extemporaneous speech honed over twenty years of teaching at universities, projects an expansive inclusivity.

In a small room downstairs, Young and a curator unloaded a cart’s worth of artifacts from the James Baldwin Papers, whose custody the Schomburg assumed earlier this year. There were telexes in red ink, drafts of Baldwin’s essay on Martin Luther King Jr., and signed playbills from his work in the theater. There were also candid, heartbreaking photographs of Baldwin in Paris, where the poet went to live in 1948 with just forty dollars in his pocket.

"To see all the ways that people got their Baldwin I think is really important."

Watching Young handle the Baldwin materials, I could see that for all his enthusiasm about the Schomburg’s programming and outreach efforts, it was here, among the yellowing typescripts and handwritten notes tucked in clear plastic sleeves, that he was truly at home. Young often talks about “the dirt and the mud and the gunk” of life as the raw material of his poetry, and his fascination with the idiosyncratic manner by which words elbow a physical path into the world was evident. Baldwin, he noted at one point, “had books that were published in crazy editions. To see all the ways that people got their Baldwin I think is really important.”

Compared with Baldwin’s early career, which he once described in these pages as a “wild process” of “failure, elimination, and rejection,” Young’s looks like a golden road of unlimited devotion. And yet just as Baldwin’s exile to a cold-water garret in Paris came to seem, in retrospect, representative of the American writer at midcentury, so too does Young’s long march through the institutions seem exemplary of our time.

He was born in 1970 to what he describes as “practical people”: His father was an opthalmologist and a former Army lieutenant; his mother was one of the first black women to earn a doctorate in chemistry from the University of Nebraska. Both had hefted themselves out of Jim Crow childhoods in rural Louisiana, the first in their families to go to college. His parents’ academic training kept the family on the move until he was ten, when they settled down in Topeka, Kansas. The overachieving only child of overachieving parents, Young discovered what he calls the “secret thrill” of poetry when a summer-school teacher mimeographed a poem he wrote and distributed it to the class. He arrived at Harvard determined to write, and his accomplishments - including helping to restart a literary magazine called Diaspora - eventually became fodder for campus folklore. Tracy K. Smith, the current poet laureate of the United States, was a few years behind Young in college. “The legend on campus,” she told me, “was that he wrote his thesis in a month.” (When I asked Young about this, he laughed and didn’t exactly deny it.)

Diaspora’s fiction editor was a would-be novelist listed on the masthead as Chipp Whitehead. Better known now as Colson, he is the author of the much-lauded novel The Underground Railroad. Whitehead told me that in contrast with his own published output at Harvard, Young was prolific. “People in college talk a lot about what they’re producing in their various pretentious ways. But he was actually already a poet when I met him at nineteen, not a poseur.”

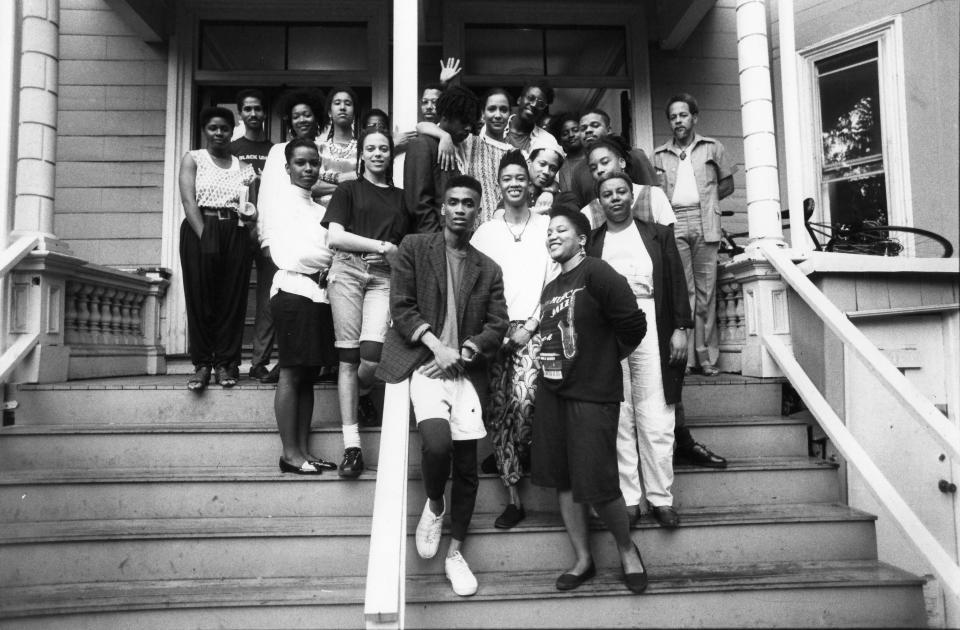

During his junior year, Young started hanging around a Victorian house in Cambridge that hosted something called the Dark Room Collective. Founded shortly after Baldwin died in 1987, the collective sponsored a reading series that paired emerging and established writers. The group lasted about a decade, and its effects on American poetry would come to rival those of the San Francisco Renaissance and the Black Mountain School. Two of the Dark Room’s alumnae, Smith and Natasha Trethewey, later won Pulitzer prizes, and Trethewey was named poet laureate in 2012, as Smith would be four years later.

Those honors were important - only three black poets won the Pulitzer in the nine decades before Trethewey; in the ten years since, three more have - but the underlying shift they signified was even more consequential. Though poetry still has a race problem, it’s at least a generation ahead of Hollywood in addressing it. According to Jordan Davis, a poet and editor, “The incalculably good effect that the Dark Room Collective has had is that it’s a much more diverse field now.” Davis remembers hearing about the collective in the early nineties. “Poets are mostly vipers,” he said, and “to have a group of poets that were so supportive of each other was a great thing to see.”

Young insists that “there’s always been really interesting, diverse black voices talking and arguing and counterpointing.” But he acknowledges that the visibility of the Dark Room and groups like it spurred broad changes in the field.“I don’t think black poetry changed,” he told me. “Maybe poetry changed and black poets changed poetry.”

In college, Young told The Harvard Crimson that “being Harvard’s Young Black Poet is really frustrating.” Twenty-five years later, he says that it was the Dark Room Collective that freed him from what he once called “the burden of representation.” The collective’s motto was “Total life is what we want,” a phrase borrowed from the anthologist Clarence Major. “ ‘Total life’ means that there isn’t anything that you can write that isn’t black,” Young told me. “Black is huge, poetry is huge, they’re huge together.”

Not everyone felt that the collective always lived up to that tall order. Carl Phillips has suggested that he was ousted from the group because “I wasn’t writing the kind of poems that were correctly ‘black.’ ” But for Young, the freedom he found in the Dark Room made all the difference. In the years since, he has written about the artist Jean-Michel Basquiat, the rebellion on the slave ship Amistad, and his father, who died in a 2004 hunting accident. In Most Way Home, his first collection, he described:

. . . watching

the eleven o’clock footage of someone beaten

blue by the cops, over & over, knowing you could

do nothing about this, only watch, knowing

it already has all happened without you

& probably will keep on happening, steady

as snake poison traveling toward the heart

Two decades later, in “Oblivion,” first published in The New Yorker, he would paint a pastoral scene that takes a sudden ugly turn toward the antebellum:

Cows keep no cry, only

a slave’s low moan.

This slight rise

they must climb.

Poems like these might give the impression, not entirely incorrect, that the lived experience of race is Young’s central theme. But to spend much time with his work - to spend much time with him, for that matter - is to recognize an organizing obsession that ties together Young’s poetry, his prose, the many anthologies he has edited, and his work at the Schomburg. In The Grey Album, he names this impulse precisely. “The willed recovery of what’s been lost, often forcibly, I suppose is what keeps me going,” he writes. “It is this reason I found myself a poet and a collector and now a curator: to save what we didn’t even know needed saving.” As he told me, “In African-American culture there’s often a family historian, someone who does the genealogy or keeps the family Bible. I became aware that might be one role the poet has.”

"Poetry was not this thing in the atmosphere. You have to look in your backyard. That's the stuff to write about."

When Young came back from Stanford, where he took classes with Denise Levertov, he told Whitehead - by then a close friend - “I’m saving everything, every single document. Denise just retired and is selling her archives.” It says something about Young’s confidence that at twenty-four he was sure he’d one day have archives worth buying. But his mania for preservation runs far deeper than any conscious calculation, as I learned from his wife, Kate Tuttle. A white editor and book critic originally from Kansas, Tuttle told me, with a laugh, that Young’s completist tendencies can be a “vexed” subject at home. (They are awash, she said, in dishware by the midcentury designer Russel Wright.) But she also said that Young had impressed her early on by mentioning that he’d read all fourteen of L. Frank Baum’s Oz books, a subject close to her Kansan heart. “When he gets one of something, he wants all of them.”

Young claims Lucille Clifton, Seamus Heaney, and Rita Dove as important influences, and says he sees music as the essence of his art. Though his poems do not lack for depth, they rarely scan as difficult, let alone forbidding. He likes puns, and freely borrows forms from other fields (the blues, fugitive-slave posters, film noir). In college, he told me, he realized that “poetry was not this thing in the atmosphere. You have to look in your backyard. That’s the stuff to write about.” At the time, he’d never read a poem that represented someone like his grandmother. “I remember thinking, If I can get her in a poem, then I’ll have done something.” Young began to look to poetry as a sort of archive, vindicating evidence of “family - blood, adopted, imagined,” to borrow the dedication of Most Way Home. In “Oblivion,” he writes what might be his motto, or maybe a fervent dream: “Nothing // stays lost forever.”

Young’s most severe critics have knocked him for imprecision, and some have suggested that he is too much in thrall to the past. John Palattella, at the time the literary editor of The Nation, wrote in 2005 that Young’s “language is often careless” and that his “preoccupation with looking back in reverence has become paralyzing instead of fructifying.” Yet nowhere is Young’s compulsion to arrest time more moving than in Book of Hours, from 2014, which includes poems he wrote after the death of his father and before the birth of his son. Young says he wanted “even the metaphors to be taken from the experience. I realize now that I was very much trying to document and record in a historic sense.” In “Near Miss,” he addresses his father:

Old man, Sir -

who, alone, in the room

with your body lying

in state

I saluted -

it is forgetting, not watery

memory, that scares me.

Young’s most recent poem in The New Yorker, and his last as long as he is poetry editor, is an ode called “Little Red Corvette” that was published in 2016, a few weeks after Prince’s death. Like “Near Miss,” it is about loss, albeit in a very different register.

Nothing passed us by. Baby,

you’re much too fast. In 1990

we had us an early 80s party -

nostalgic already,

I dug out my best

OPs & two polos, fluorescent,

worn simultaneously -

collar up, pretend preppy.

That The New Yorker would publish something like this - not just a timely elegy but a timely elegy to a rock star, one whose setting is a sweaty college dance party - ought not have surprised anyone who had paid close attention to the sorts of poems the magazine has been publishing since Paul Muldoon took over in 2007. But it is likely news to everyone else - which is to say, roughly, everyone.

After all, for much of the twentieth century, the magazine couldn’t escape the rap leveled by Elizabeth Bishop, who complained in 1940 that its editors “want all New Yorker poetry to sound like New Yorker poetry.” Muldoon pushed the limit of what was palatable to the magazine’s million-plus subscribers, but even under his editorship The New Yorker was never a faithful barometer of the art. (I worked there for several years, but not in the poetry department.) If you wanted a broad but still incomplete overview of the field, you subscribed to Poetry. If you really wanted to know what was happening, you strapped on your shin guards and went scrabbling around in little magazines and on the Internet.

Nevertheless, most poets would walk four miles through flaming snot to appear in The New Yorker’s pages. The reason is simple: In a culture that remembers poetry only on its holiest occasions - weddings, funerals, Beyoncé concerts - The New Yorker remains one of the last places where civilians have a chance of running headlong into a previously unpublished stack of verse. Kenneth Koch joked that publishing in the magazine was the only way your psychiatrist would ever see your work.

Jordan Davis sees a natural fit between Young’s poetry and the role he’s just taken on. “He holds a sort of senatorial authority,” Davis told me. “He has really mastered the popular voice and speaking to enormous public concerns. It’s a kind of public-speaker role for poetry that has gone unoccupied pretty much since Allen Ginsberg died.”

Though the popularity of poetry in previous eras is often overstated, it’s nevertheless true that the great cultural “we” did once look to poets like Ginsberg to tell us something essential about ourselves and our world. When I asked David Remnick, the editor of The New Yorker, why the magazine still publishes poems, he held fast to that ideal. “Poetry is arguably, in some compressed and magical fashion, the highest form of expression, the greatest devotion we have to our most intricate invention, language itself,” he wrote in an email. “How can we publish a magazine that proposes to be literary, as well as journalistic, that does not publish poetry?”

Tuttle said that despite her husband’s allegiance to history, his tenure at The New Yorker could be “revolutionary” in at least one sense: “It’s significant that he’s the first black poetry editor there.” In 1992, Young told the Crimson, “Even if we were all published in The New Yorker, would that be the point? You’re missing the point if it’s a new driver driving the same old truck.” Now that he has the keys in hand, however, he is careful not to say anything that could be construed as criticism of his predecessors. He wants the work he chooses to “be a public thing,” he told me, “to really represent poetry” in all its breadth. In a world crowded with push notifications and tweets threatening nuclear war, poetry’s job, he said, “is to take us out of ourselves and bring us back a little bit different. That’s a lot to put on any one poem, but I think you can put it on poetry in general.”

You Might Also Like