KC’s riverfront used to be a dumping ground. Now, it’s getting a massive makeover

A dust cloud two blocks wide rose from the rubble of Wayne Miner Court, a public housing complex on Kansas City’s East Side. It hung in the cold rain like a shroud over 11th Street and Woodland Avenue, where five high-rise apartment buildings had collapsed seconds earlier from a planned implosion carried live on TV.

Slowly, the cloud drifted toward downtown and dissipated over the city’s riverfront where, in the weeks following the blast, nearly all 34,000 tons of the rubble were dumped in the shadow of the Heart of America Bridge. The bureaucrats at City Hall figured it would be cheaper to pile it along the river than hauling the mess to a licensed landfill.

Even back in 1987, the decision seemed stupid and shortsighted.

“We might be creating a monster for future development of the site,” councilman and riverfront supporter Mike Burke said at the time.

“Might” is not the half of it, says Jon Stephens, CEO and president of the Kansas City Port Authority, aka Port KC. The workers developing the area now battle the monster every day, he says.

“We have also found some of the bricks of Wayne Miner housing center. They dumped the bricks and some of the concrete material down here,” Stephens said.

For generations, the city’s leaders had said they were committed to bringing new life to the forlorn and forgotten waterfront where Kansas City got its start.

They even considered building a 30,000-seat baseball stadium there in the 1950s in hopes the city could attract a major league team when Kansas City was strictly minor league.

But instead of that kind of investment, the 134 acres of riverfront property the city purchased for that ballpark became a dumping ground. These days, you never know what you’ll find when you sink a shovel into that land between the Heart of America and Christopher Bond bridges.

“Down by the beer garden, you’ll see a big, rusty heap of bent metal that was dug out (while we were) putting in the stormwater detention coffers,” Stephens said between sips of coffee in his office near the riverfront one sunny morning this spring.

But then, think of finding rusty metal at the site of a new beer garden as a sign of changing times on the city’s riverfront.

After decades of dumping and neglect, the area has been gradually transforming as part of the city’s latest development boom that started around 2014.

But now, that’s ramping up, and not so gradually. The area is in the midst of a full-on renaissance.

A graveyard of Kansas City developments past

Developing the riverfront has been no small task.

Workers unearthed those bricks from the old public housing complex while sinking hundreds more piers into the ground than they might normally have needed for the apartment buildings that now rise above them.

The ground wasn’t stable.

“It’s rubble underneath,” Stephens said.

But you wouldn’t know it.

Speaking of rubble, after the Kemper Arena roof collapsed in 1979, the city’s brain trust had those chunks of concrete dumped along the riverfront, too. They were piled near where the KC Current’s AD Franch now defends the south goal on match days at CPKC Stadium.

“And you had large-scale oil transfer stations and fuel that fouled the soil that had to be cleaned up,” Stephens said.

As he ran down the list of all the nasty things that were dumped, buried or spilled along the riverfront over the decades, a worker at the controls of an excavator was at that very moment piling more scrap metal near the steel frame of the future home of Two Birds One Stone. That’s going to be the name of the beer garden on River Front Drive where, later this summer, thirsty customers will be able to watch the driftwood flow down the Muddy Mo as they sip their IPAs.

Across the street, other hardhats were putting the finishing touches on the five-story, 118-room Origin Hotel that the same Mississippi developer, Thrash Group, plans to open this year.

Why is this all happening now when so much didn’t happen for so long?

To put it simply:

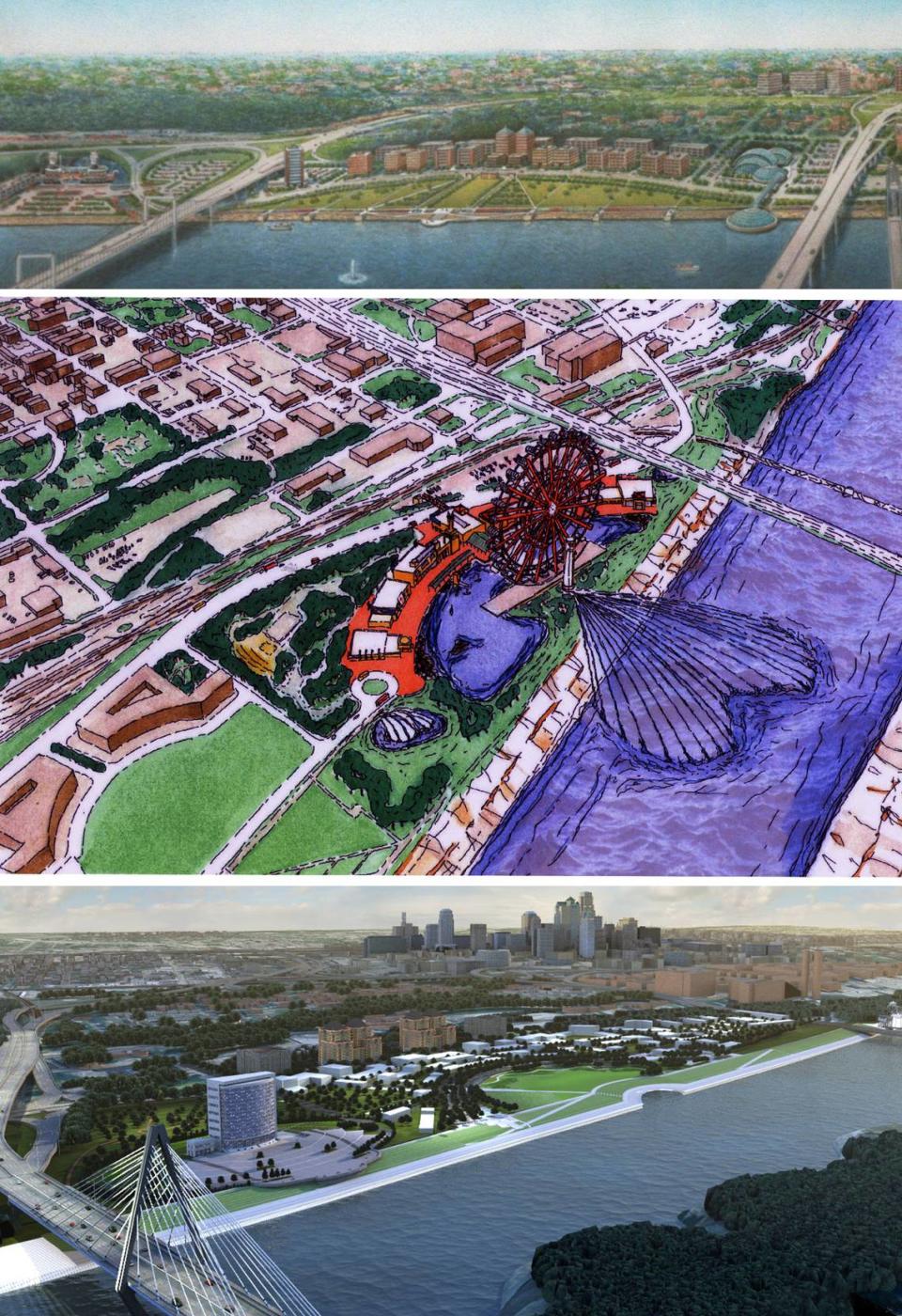

“There was plan after plan after plan after plan laid down here,” Stephens said.

Seeking a super developer

Ten years ago, about the only thing to be found along this stretch of the riverfront was 17-acre Berkley Riverfront Park, which The Star once aptly described as “a lonely strip of greenery along the Missouri River.’’

Now frequented by runners and dog walkers, the park was built atop rubble in the 1990s by the port authority, which the city created in 1979 when the park’s namesake, Richard L. Berkley, was mayor.

“The riverfront has been a forgotten area, and we hope to change that,” Councilman Leon Brownfield said then.

But the Missouri legislature, which for decades had resisted giving the city the power to create the port authority, did Kansas City no favors. While Port KC can buy and sell property, issue revenue bonds to help developers and regulate construction along the river, it can’t levy taxes.

The revenue stream it needed to get big things done — like building the park and a new Grand Avenue viaduct to provide better access to the area — didn’t begin to flow until the state authorized casino gambling along the Missouri and Mississippi rivers in the mid-1990s.

Lease payments from the casino now known as Bally’s Casino-Kansas City helped pay off the debt on the money borrowed for those projects.

Building the park, the port authority board thought, would spur office development like Corporate Woods in Overland Park. There was big talk of building an aquarium, a hotel and condos beside the greenspace.

All the port authority needed was for some “master developer” to swoop in and make it all happen, with the aid of big breaks the agency was empowered to offer. The city’s tax increment financing commission was also ready to make deals.

But multiple requests for proposals for someone willing to be that dynamic risk taker led to nothing, and the park opened to savage reviews.

“The Port Authority’s $30 million gamble to spur redevelopment along Kansas City’s long-ignored riverfront has been a big failure,” Star columnist Yael T. Abouhalkah wrote in February 2000.

Even the port authority’s chairman at the time, Bill Johnson, found the park wanting.

“It looks like a tree farm,” he told the Abouhalkah. “A park isn’t a park without people.”

People came for the occasional weekend festival, as they still do. Riverfest, Oktoberfest and Irish Fest took turns staging events. But people mostly stayed away.

The port authority kept at it during the 2000s. Money flowed in from court settlements and the federal government to clean up what remained of the contaminated soil around the park. And the authority stayed focused on finding that Superman master developer to turn the 55 acres south of the park into an “urban village.”

A couple groups did come forward, but they didn’t get anything going. Port KC shifted focus. Maybe the secret would be to entice the U.S. General Services Administration to build a new federal office complex there.

“We think it’s a knock-your-socks-off site for the GSA or a similar office use,” the project planner for one of the port authority’s development partners said in 2007.

But Uncle Sam kept its socks on and walked away.

‘One parcel at a time’

Then came the Great Recession. And coming out of it, the port authority, under new management, decided that maybe it was time for a whole new approach.

“How about we lose the master developer thing and start marketing riverfront land one parcel at a time?” Stephens’ predecessor Michael Collins and his vice president of real estate, Joe Perry, proposed.

The apartment buildings, the the dog park bar, the soccer stadium and all the rest that’s now moving forward to the point that Stephens predicts the riverfront will be fully built out in a decade or so? It all flowed from that change in strategy.

“That turned out to be a good plan because breaking it up into more bite-sized, two-acre, three-acre pieces made it much more marketable and allowed the riverfront to develop more organically,” said Gib Kerr, the real estate agent the port authority hired to market the area to developers.

“That was the plan. And it’s worked pretty well.”

The port authority had by then gotten title from the city to all the rest of the land around the park that had undergone environmental remediation. The toxic dirt was gone or covered up for good.

An Indiana-based developer, Flaherty & Collins, got things moving in 2014 with its $75 million Union Berkley Riverfront apartment project, which broke ground two years later.

Four stories high and full of amenities — four fitness centers, patios with fire pits, dog washing stations — the project was aimed at attracting millennials who could afford to pay at least $1,000 for a studio apartment, with prices ranging up to $7,000 for a penthouse view of downtown and North Kansas City.

“I gotta hand it to Flaherty & Collins,” Kerr said. “I love dealing with people from out of town because they bring a fresh perspective. … They got here and were like, ‘Wow, nobody’s developing on the riverfront? That’s crazy!’”

Leib Dodell and David Hensley were next in 2016, with their idea to build a combination dog park, restaurant and bar made out of shipping containers on two acres shadowed by the Heart of America Bridge that they called Bar K. They committed to the space at a time when dogs were suddenly proliferating around downtown because so many people with dogs were moving into all the new apartments that had gone up within the River Market and freeway loop.

“It has grown beyond all our expectations,” Dodell told a podcaster.

Stephens replaced Collins around then as head of the port authority, which rebranded as Port KC in 2015, and acknowledges that his arrival in the job was perfectly timed because so much was already going on.

“Michael Collins did an incredible job over a decade of really laying the groundwork for getting the riverfront moving and off the ground,” he said. “And before that, Mike Burke and Congressman Cleaver, when he was mayor.”

But the Mizzou journalism school grad turned economic development guy has presided over all that has come since. Overland Park-based NorthPoint Development opened its $60 million CORE apartment complex in 2020 with 355 units next to Bar K with plans now for a second phase in the works.

His philosophy: “Let’s stop sharing big, beautiful renderings, and then not bringing them to life. Let’s talk about what we can accomplish together and what we can accomplish now.”

Influence of the Current

The riverfront’s biggest success story began to take shape at the end of 2020. Local financiers Angie and Chris Long founded an expansion National Women’s Soccer League franchise, and that next October announced plans that they would privately finance the first stadium ever built specifically for a pro women’s sports team.

That the stadium would be at the east end of Berkley Riverfront Park simplified the choice of a new name for the team, which had been operating without one that first season.

The Kansas City Current was born the same week that Port KC announced that the team would be signing a long-term lease for the land underneath a $70 million stadium, whose cost rose to $117 million by the time it was finished and more seats were added to the original proposal. That bump also caused the Current to ask for the city’s help in applying for $6 million in state tax incentives.

This first season, the now mostly privately financed CPKC Stadium has seen nothing but sellout crowds, and the Longs have gone on to further their partnership with Port KC. They finalized a deal with their partners at Chicago-based Marquee Development to invest $800 million around the stadium to build hundreds of apartments, 10% of which would be affordable for renters who make up to half of the area’s median family income as set by the federal government.

They also have plans for restaurants, shops and more than two acres added to Berkley park.

Port KC guaranteed the developers huge tax breaks on property that now generates almost no tax revenue: 90% to 95% for 15 years on the apartment projects and 70% on office and retail space for the first 10 years and 30% for the final five years of those 15-year tax exemptions.

Even though millions of dollars will eventually flow to local taxing jurisdictions, the Kansas City Public Schools questions whether Port KC needs to be so generous.

The district says non-city agencies like the port authority and the Kansas City Area Transportation Authority give away potential public funds without performing the third-party financial analysis that the city’s economic development process requires.

“KCPS is concerned this practice leads to some projects getting more public subsidy than is necessary.” the district says.

Stephens doesn’t apologize for Port KC’s generosity with public subsidies. The riverfront wouldn’t have developed without them, he said, but the strategy has been to scale back on the size of the handouts as each new project comes forward.

“The goal is to continue to move the needle down and have them pay more and more and more as you get more product,” he said. “But you know, along those lines, I’ll tell you that when I came in, I set a goal of how we were going to speed up the growth here.”

The vision for a denser riverfront

About 1,500 people now live in the luxury apartments near Berkley park. Eventually, it will 5,000, if everything works out the way things are heading.

So improving transportation links to the riverfront is a must, as Stephens sees it. Plans for a new pedestrian bridge between the riverfront and the River Market are progressing, but the money for it hasn’t been raised yet to shorten the walk between the River Market and those apartment dwellers.

“They’re going to want to walk up to the farmers market, and they’re going to want to go up there to eat, and vice versa, so we need that,” Stephens said.

Port KC is also working with the city to connect the cycling path through the park to the West Bottoms, and KC Streetcar will have a stop near Union Berkley when an extension from the River Market is completed in 2026. Volleyball players in the newly relocated sand courts between Union Berkley and the river in Berkley Riverfront Park will be able to wave at the passengers coming and going on that line, which will stretch all the way to University of Missouri-Kansas City by then.

Stephens also has his eye on making the rough, tree-lined north bank of the Missouri River between the Bond bridge and the new Buck O’Neill Bridge accessible to hikers and bikers. That land is now choked with vines and weeds and would make a great park, he thinks.

It’s a lot of stuff to work on, but Stephens has no doubt his organization will get it accomplished.

“As a kid growing up here, there were so many big visions that came and went in our city, and I think it just leads to a disbelief that anything good will happen in our city,” he said.

“And so in our little Port KC I’ve tried to say ‘no, we’re going to do what we say and we’re not going to say anything until we’re ready to do it and do it the right way.”