All this KC man wanted was bloody revenge. Here’s what changed his mind, and his life

Physically, John Roddy recovered from being shot four times in 2015. But he couldn’t get over an all-consuming thought: revenge.

For weeks he would lie in wait on the block where he suspected the shooters lived, hoping he could gun them down.

“Killing them, that’s it,” Roddy said. “I didn’t care if they had their baby in their arm, they all getting shot.”

The chance never came.

After years of navigating his obsessions and trauma without help, Roddy, 32, finally learned how to lead a healthy life, thanks to therapy and social services at the Kansas City nonprofit Dads Against Crime.

Back when he was 17, Roddy was already making a name for himself robbing drug dealers at gunpoint and getting into shootouts.

In 2008, he and an accomplice planned a carjacking. They staked out a victim, and Roddy banged on the vehicle’s window with a sawed-off shotgun. The victim tried to drive away, but Roddy pulled the trigger and shot her in the face.

Roddy spent 10 months inside of Jackson County Detention Center and eventually was found guilty of second degree assault and first degree armed robbery. He was released with time served and sentenced to five years of supervised probation.

He then developed a runaway cocaine addiction. He was hanging out with the wrong people.

In September 2015, Roddy was on the front porch of his cousin’s home on the 3600 block of Bellefontaine Avenue. Two men in hoodies approached and opened fire. Roddy was not the intended target but was shot four times.

Finally, he built a new, clean life for himself, running a successful over-the-road trucking operation, starting a family and buying a house. But the trauma was lying in wait. Paranoia and depression took over. He thought about suicide. His marriage grew fractured.

“I’m not feeling like being a husband, I feel like being nothing, I barely feel like being here on this earth,” Roddy said.

With nowhere else to turn, Roddy wrote on Facebook that he felt death surrounding him. Andre Harris, the founder of Dads Against Crime, saw it and connected him with a therapist.

“I do know that DAC helped me a lot,” Roddy said. “The counselor that DAC provided, he helped me get through this.”

The therapist not only helped him but saved his family and marriage.

“The counselor focused on me and my wife, my marriage wouldn’t be here, man.”

He no longer feels he has to carry a gun everywhere he goes. He doesn’t feel as if he’s about to be killed.

“I’m still working on some things but I’m in a way better spot,” Roddy said. “I got a good job, a career, my wife is here and my daughter is here.”

“I’m really blessed and thankful.”

How Dads Against Crime came to be

In 2020, the Kansas City community was outraged over the death of 4-year-old LeGend Taliferro, the victim of stray bullets from a gunman out for revenge against relatives.

Out of that outrage, Andre Harris created Dads Against Crime. He started the nonprofit to help men whose children were victims of gun violence. Harris soon expanded it to help any man in Kansas City. His goal: to break the cycle of violent crime.

“We either got to change it now or crime going to show up in the nicest neighborhoods you can think of,” Harris said. “There’s going to be violence everywhere.”

The organization acts as a catchall for social services, providing free therapy, rent and utility assistance, job placement, child support services and felony expungement.

Funding comes largely from a few private donors and individuals via online donations.

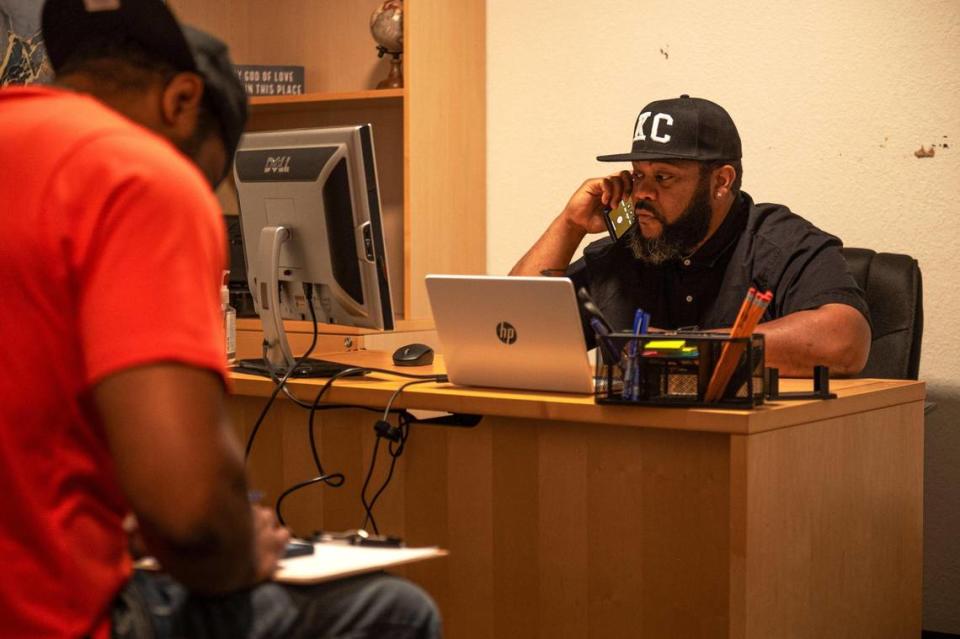

One day by 8 a.m., Harris’ phone is already flooded with calls. Each day, he schedules appointments and takes walk-in visits.

“This is my mission,” Harris said. “My purpose in life is to help as many men as I can.”

Harris said he focuses on men because, according to FBI data, they accounted for 76% of Kansas City’s violent crime offenders in 2021.

“It’s not the women on the blocks with the guns. It’s not the women on the block and killing people. It’s not the women that are killing kids. The men are,” Harris said.

Matching men with jobs

Clients meet with Harris at his office on East Blue Parkway Drive just outside of Raytown. They fill out forms and get placed at one of Harris’ partner companies.

Employers include Midwest National Rubber, You Move Me, All My Sons Moving and Challenge Manufacturing Co. They must be willing to hire men with felonies, some with little or no work experience, and pay at least $15 an hour.

Harris contends that by providing essential services, Dads Against Crime can stop crime before it happens.

“I’m not for murder and I’m not for robbing, I’m not for stealing,” Harris said. “But if I had to give the robber a job to keep him from robbing people, then it’s best I get this man a job to keep him from robbing people.”

Carrying baggage

Harris knows firsthand where his clients are coming from.

“I sold drugs and I did good,” Harris said. “I enjoyed waking up, looking up from under my bed and seeing a stash bottle full of cash.”

The money kept flowing but so did the bodies. Harris said that out of the 26 friends he used to run the streets with, 22 of them are dead.

When he left the street life, he carried with him the baggage of trauma that he was only able to unpack once he entered therapy.

“I didn’t realize that I was dealing with PTSD,” Harris said. “From me always looking out of my rearview, pulling into a parking lot and always reversing in — because I was always in my mind like, ‘I need to be ready in case somebody pulls up on me to hurry up and smash out of here.’”

Each of his clients is guaranteed 20 free therapy sessions.

When a client gets a job, starts therapy or receives other services, Harris stays in touch.

“We’re going to be checking on you. We want to make sure that you stay the right path,” Harris said. “If you venture off that path, it’s ‘bro, how can we get you back?’”

He routinely calls and texts his clients, letting them know that he is thinking of them and that he is proud of them.

“Give me the worst person,” Harris said, “I promise you, if they feel genuine love, they can change.”