Kavanaugh contradicts White House account of credit card debt, raising more questions

On Wednesday night, Supreme Court nominee Brett Kavanaugh offered answers for the first time to long-standing questions about his personal finances that had been prompted by significant credit-card and loan debt noted on his judicial disclosure forms. Kavanaugh’s explanation of his finances is not consistent with earlier explanations from the White House.

Questions have lingered since shortly after Kavanaugh’s nomination was announced in July and reporters digging into his public record found that Kavanaugh’s financial disclosure forms showed tens of thousands of dollars of fluctuating credit card balances as well as a loan against his retirement account for the 12 years before 2017. All of these debts disappeared from Kavanaugh’s financial disclosures in 2017 and the forms did not indicate an obvious source of funds to repay them, prompting speculation about potential conflicts of interest.

In July, White House spokesman Raj Shah offered an explanation of the debts to the Washington Post: that Kavanaugh had purchased season tickets to the Nationals for a group of friends, putting them on his credit card near the end of a year and collecting reimbursements the following year. That practice, along with some home-improvement expenses, resulted in the large year-end balances that appeared on his disclosure forms. Shah emphasized that Kavanaugh’s credit card balances were transitory and that he had discontinued the practice in 2017. “He did not carry that kind of debt year over year,” Shah told the Post.

Before his hearings last week, Kavanaugh and the White House declined to answer any further questions, from reporters and senators alike, about the nominee’s finances. No senators asked about Kavanaugh’s financial situation during the televised hearings, but Democrats on the Judiciary Committee submitted several detailed questions in writing afterward.

Kavanaugh’s answers, released on Wednesday, contradict the White House account in many important respects. “Over the years, we carried some personal debt,” Kavanaugh wrote, referring to himself and his wife. But he denied that the debt was related to the baseball tickets in the way Shah had described — which would have amounted to loaning his friends the cost of their tickets until they got around to reimbursing him.

Kavanaugh says he signed up for 12 years of Nationals season tickets when the team moved to Washington, D.C., in 2005. “I am a huge sports fan,” Kavanaugh explains. He split up those tickets with “old friends” (whom he still declines to name) through a ticket draft held at his house. However, Kavanaugh wrote, “Everyone in the group paid me for their tickets based on the cost of the tickets, to the dollar. No one overpaid or underpaid me for tickets. No loans were given in either direction.”

The White House account implied that Kavanaugh had in effect loaned his friends the cost of the tickets for at least a month or two, while he financed the expense on his credit cards. Kavanaugh did not repeat that claim. (After this story was published, a White House official called to say the administration’s account of the baseball ticket arrangements is not in conflict with Kavanaugh’s, and the Washington Post report from July “is misleading.”)

The new account revives questions about Kavanaugh’s overall financial situation, and suggestions that he lived beyond what he could afford on his relatively modest income as a federal circuit court judge. The version told by the White House in July had addressed that question, but had the drawback that it struck many observers as unlikely. “It’s strange to imagine that a man of comparatively modest means would put tens of thousands of dollars on credit cards to buy baseball tickets,” the Atlantic’s David Graham wrote at the time. Many also noted that Nationals’ season tickets simply aren’t expensive enough to explain such significant debt. And the friends who supposedly were part of this arrangement have never been identified or come forward.

Kavanaugh’s new story about his credit card debt has the advantage of being far more plausible, allowing for the fact that it paints Shah as, to put it politely, misinformed. Many people’s finances are a balancing act of sorts. It is eminently believable that the Kavanaugh family ran up substantial personal debt on their credit cards while they were trying to juggle living on a judge’s salary and bearing the expenses associated with climbing the ranks of Washington society, including membership in a ritzy country club. The new story no longer involves an eye-rolling account of a federal judge incurring high-interest credit card debt for unnamed friends. But it is notably missing the facts and figures that would allow others to verify its claims.

For all its plausibility, Kavanaugh’s explanation renews some of the serious concerns that Shah’s initial account obscured. A federal judge and his wife were saddled with a credit card burden that, in fact, they did carry year over year — a financial anchor from which they couldn’t seem to free themselves for nearly a dozen years. Anyone with the experience of carrying a significant credit card balance knows the pressure that revolving interest at high rates puts on a family. How much interest did they ultimately have to pay? How did the Kavanaughs manage to stay afloat during 12 lean years? What deals and compromises, if any, did they make to do so?

And, perhaps the most concerning question: How did they manage, in 2017, to make all that debt go away?

Examined closely, the new story still does not provide a certain answer for how Kavanaugh repaid his credit credit cards; it contains an unexplained three-year gap.

Kavanaugh’s written answers suggest, without stating directly, that the source of funds for repaying his credit card debt were “a significant annual salary increase for federal judges” and “a substantial back-pay award in the wake of class litigation over pay for the federal judiciary.” A class-action case decided in 2013 resulted in a pay increase and back pay for federal judges that started in 2014. Kavanaugh’s salary should have increased that year by $26,700 per year starting in January 2014 and he should have received approximately $150,000 in back pay as a lump sum in 2014 as well, according to a question posed to Kavanaugh by Sen. Richard Blumenthal of Connecticut.

However, Kavanaugh’s credit card debt problem was not solved in 2014. In fact, after declining somewhat from 2013 to 2014, Kavanaugh’s credit card balances increased dramatically during both 2015 and 2016, reaching levels in 2016 higher than they had been for a decade. The credit card balances finally vanish in 2017. The infusion of funds in 2014 also had no discernible effect on the balance of the loan Kavanaugh had taken against his Thrift Savings Plan, which does not appear to decline until three years later, in 2017. Kavanaugh’s written answers suggest this loan was repaid with regular deductions from his paycheck, rather than all at once.) The reported balance in Kavanaugh’s bank accounts doesn’t increase or decrease in 2014 or afterward, even though Kavanaugh should have been depositing bigger paychecks and a $150,000 lump sum payment. If for some reason Kavanaugh waited until 2017 to use his 2014 infusion of funds to pay down his credit cards, where did he deposit all that money in the interim? Neither Kavanaugh’s disclosure forms nor his written explanation contains an answer. What accounts for the continued increases in Kavanaugh credit card debt after 2014? Again, we have no certain answers.

If Kavanaugh’s 2017 repayment of his debts is not directly derived from the infusion of money he received in 2014, where did it come from?

One possibility is that Kavanaugh extracted some equity from his home, through a cash-out refinancing or a second mortgage. However, Maryland real estate records reviewed by Yahoo News reveal that Kavanaugh refinanced his home twice, in 2014 and 2015, and neither refinancing increased the face amount of the mortgage; that appears to rule out a cash-out refinancing. In addition, there is no record of a second mortgage or home equity line of credit on the property.

Another possibility is a wealthy benefactor. Kavanaugh’s written answers state that he has not received any financial gifts from anyone, “other than from our family which are excluded from disclosure in judicial financial disclosure reports.” Did his parents or other relatives pay off his debts? A gift from family appears to be the most plausible answer that is consistent with Kavanaugh’s written responses; however, nowhere in his answers does Kavanaugh confirm this seemingly harmless explanation.

Family help could also explain how Kavanaugh raised the down payment for his $1.2 million home in 2006. In his written explanation, Kavanaugh attributes this down payment primarily to the Thrift Savings Plan loan; however, according to Kavanaugh’s disclosure forms, that loan can only have provided up to $50,000 of the approximately $220,000 in cash that would have been due. How did Kavanaugh raise the other $170,000? His bank accounts don’t show the declining balances normally associated with making a sizable down payment. The funds might have come from his family, or maybe he put it on his credit cards.

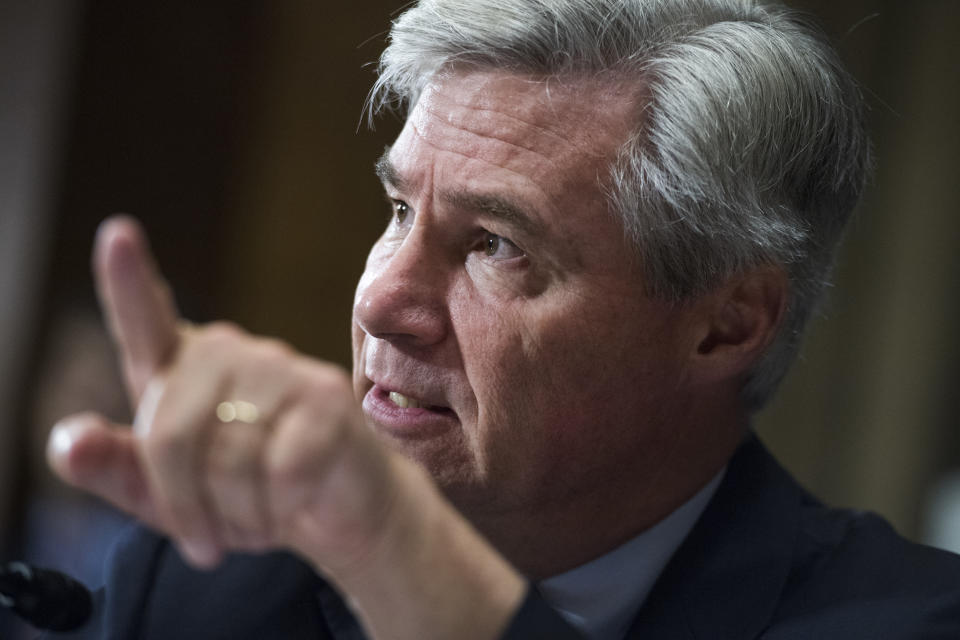

The strange details in Kavanaugh’s disclosure forms, and the White House’s implausible gloss on them, fueled rumors throughout the summer of a darker explanation for Kavanaugh’s significant debts — some including gambling. These rumors were given some limited substance during the hearings when Democrats released and circulated one “committee confidential” email in which Kavanaugh apologizes to his friends for “growing aggressive after blowing still another dice game.” Sen. Sheldon Whitehouse of Rhode Island added fuel to the fire by asking Kavanaugh several highly specific questions about gambling, including whether he had “ever sought treatment for a gambling addiction” and whether he had “ever had debt discharged by a creditor for losses incurred in the State of New Jersey.” In his answers, Kavanaugh flatly denied that he had ever sought treatment, had such a debt discharged, or accrued gambling debts at all. Asked what had prompted such specific inquiries, a spokesman for Senator Whitehouse declined to comment on “our sourcing for these questions.”

Many Americans have complicated financial situations. Nevertheless, we ask federal judges and judicial nominees to disclose their affairs sufficiently to show that there are no unknown conflicts of interest that could interfere with the judge’s ability to do their job. After months of questions about Kavanaugh’s personal financial situation, it remains nearly as murky as it was the day President Trump called him forward in the East Room.

_____

Read more from Yahoo News: