JWST Spots Most Distant Black Hole Merger Yet

From 13 billion light-years across the gulf of space and time, we've just caught a glimpse of the most distant black hole merger discovered yet.

Using JWST, an international team of astronomers has discovered two supermassive black holes, and their attendant galaxies, coming together in a colossal cosmic collision, just 740 million years after the Big Bang.

This discovery could be a clue that helps us piece together where supermassive black holes came from, and how they grew so large, so early in the history of the Universe.

"Our findings suggest that merging is an important route through which black holes can rapidly grow, even at cosmic dawn," says astronomer Hannah Übler of the University of Cambridge in the UK.

"Together with other Webb findings of active, massive black holes in the distant Universe, our results also show that massive black holes have been shaping the evolution of galaxies from the very beginning."

Black holes are full of mysteries, and one of the most fascinating is the origin of the big ones. The smaller ones, up to about 65 times the mass of the Sun, can be explained by the supernova and core collapse of massive stars; slightly larger ones can be explained by the collisions and mergers of these collapsed stellar cores.

Supermassive black holes, millions to billions of times the mass of the Sun, could theoretically also grow this way, through a succession of hierarchical collisions between larger and larger black holes, but this process should take quite a long time.

One problem is that we've seen very large black holes at the beginning of the Universe, too soon for them to have had time to grow by this slow route.

A possible solution is that the initial "seeds" from which the black holes formed were huge to start with. But even if this is the case (which is looking increasingly likely), it's also probable that collisions and mergers played a role in growing these black holes to even bigger sizes.

One of JWST's missions is to help us figure out how the Universe formed in the wake of the Big Bang, using its powerful infrared capabilities to peer into the Cosmic Dawn (the first billion years after the Universe winked into being) with the highest resolution yet. And one of the things astronomers and cosmologists have been looking for specifically is supermassive black holes.

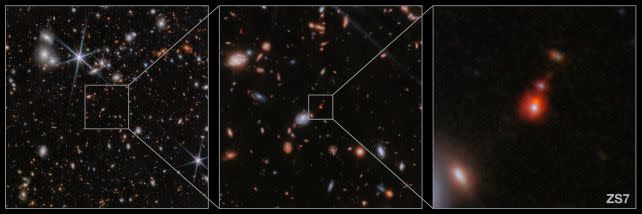

During one of its surveys, it picked up a pair of galaxies on a collision course, a system now known as ZS7. At the center of each galaxy is a supermassive black hole. And both black holes are actively growing, a process that causes the dust and gas roiling around them to blaze with light.

"We found evidence for very dense gas with fast motions in the vicinity of the black hole, as well as hot and highly ionized gas illuminated by the energetic radiation typically produced by black holes in their accretion episodes," Übler says.

"Thanks to the unprecedented sharpness of its imaging capabilities, Webb also allowed our team to spatially separate the two black holes."

The researchers were able to determine that one of the black holes clocks in at around 50 million solar masses. The other was less amenable to measurement, since the gas and dust around it was incredibly dense, but probably has a similar mass.

We've seen other such merging systems later in the Universe; in fact, mergers are thought to be a fairly important part of the growth of a galaxy. But the detection of such an early one shows that the model involving both mergers and larger black hole seeds in the first place is very plausible indeed.

Such huge mergers are thought to produce a constant hum of gravitational waves resonating throughout the Universe.

The wavelengths of this hum are too large to be detected with current gravitational wave instruments (although we may have detected it using pulsars), but by identifying ongoing mergers across different cosmological epochs, scientists can better estimate the rate at which they occur, and their contribution to the Universal hum.

"Our observations provide clear and robust evidence for a massive black hole involved in a merger with another galaxy, likely hosting another accreting black hole, at z = 7.15, only 740 million years after the Big Bang," the researchers write.

"Overall, our results seem to support a scenario of an imminent massive black hole merger in the early Universe, highlighting this as an additional important channel for the early growth of black holes. Together with other recent findings in the literature, this suggests that massive black hole merging in the distant Universe is common."

The research has been published in the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society.