Justice or vengeance: At 18, she killed 6 in fire. Will Cindy White, now 66, die in prison?

This is the first part of an exclusive IndyStar story about Sarah "Cindy" White, who was convicted on six counts of murder as an 18-year-old in 1976 for setting a fire that killed a Greenwood family of six. You can read the second part here

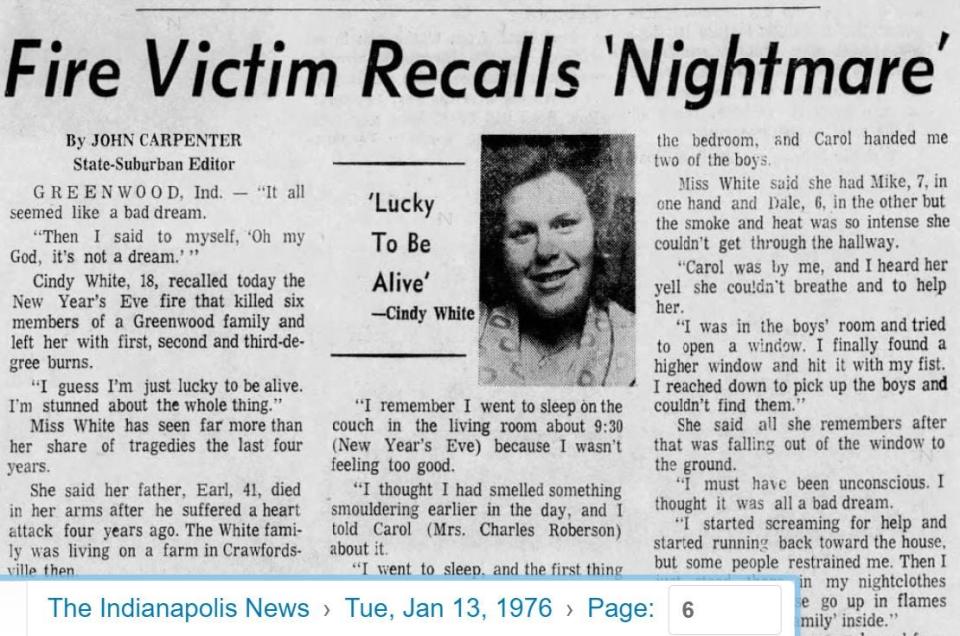

Sarah White screamed as flames burst out of the large front window of the house she just escaped.

Her hair was singed, her body covered in soot that stained her skin the color of charcoal. It was the middle of winter, and the temperature hovered in the low 30s. But the 18-year-old was wearing only thin pajamas. Her bare feet were caked in mud.

Within minutes, the single-family home at 24 Sayre Drive in Greenwood was engulfed. Acrid black smoke filled the neighborhood as the fire tore through the roof, shooting flames 30 feet into the sky.

Still, White tried crawling back into the inferno. Neighbors and first responders struggled to hold her back.

"My God," she wailed. "They're in there, the whole family!"

Charles and Carole Roberson and their four young children died in the Dec. 31, 1975, fire that destroyed their home. White, their live-in babysitter, was the lone survivor.

Officials initially looked into whether the New Year's Eve fire was caused by faulty Christmas tree wiring. But two months later, investigators settled on a different, more sinister conclusion.

The fire was arson. And White had started it ― a desperate act she initially denied but would finally admit to more than a decade later.

Within six months of the devastating fire, White was tried and convicted of arson and six counts of murder. It was a stunningly swift resolution unheard of in today’s criminal justice system. On May 21, 1976, as Hoosiers geared up for the Indianapolis 500 that would deliver Johnny Rutherford his second victory, a judge imposed one life sentence for each of the six victims.

The penalty was meant to ensure she would never leave prison alive.

Now 66, White has spent nearly 48 years behind bars, much of it at the Indiana Women's Prison. She's been incarcerated longer than any woman there. She has seen hundreds come and go in that time. She's also seen others die alone behind the prison fences. It’s a fate White still hopes to escape — despite facing essentially a death sentence — with what is likely one final push to win her freedom.

Strong opinions abound when it comes to Indiana's longest-serving female prisoner. Some will never see beyond the cold-blooded "killer nanny" she was portrayed as in court and online. Others see her as a troubled teenager whose impulsive response to years of sexual abuse led to a horrible tragedy.

Whatever the truth may have been at the time, it no longer defines White.

The case of Sarah "Cindy" White: Indiana woman convicted of killing 6 continues fight for freedom

She's now an elderly woman who spends her days in a wheelchair after suffering multiple strokes. She passes her time watching TV, folding laundry, washing dishes and crocheting items for other incarcerated women to send home to their children.

To White’s supporters and sympathizers, and there are many, her case raises questions about the punitive value of life sentences, particularly for young first-time offenders, as well as the morality of permanently imprisoning a deeply damaged teenager whose mental and emotional growth was stunted by a long history of physical and sexual abuse ― a key part of White's story that jurors never heard.

Charlie Asher, an Indianapolis attorney who’s been working since the 1990s to free White, said she never intended to kill, but she has been punished as if she did.

"We’ve sentenced someone who acted out of desperation and victimhood with no intent to hurt anyone," Asher said. "What does that say about our legal system?"

Lance Hamner, the prosecutor in Johnson County where White was tried and convicted, once called her actions "diabolical" and previously opposed granting clemency.

Despite the passing years, the after-the-fact abuse allegations, and White's good conduct in prison, Hamner said the basic facts of the case have not changed: Six people died, and four of them were young children.

"She took six lives," he said, "and the penalty for what she did should be life in prison."

Who is Sarah Isabel White?

Four years before the fire, White watched from the front porch of her family's home in Ladoga as an ambulance drove away with her father. He'd just had a heart attack, she told IndyStar in an exclusive interview, and her mother asked White and her siblings to pray for him to come home alive.

As the ambulance rolled out of sight that summer day in 1971, the 14-year-old said a prayer. But it wasn't for what her mother wanted.

"God, don’t let him live," she remembers silently asking. "Don’t let him live."

Earl White died in July 1971 at the age of 45. His daughter feared God had answered her prayers, and her father's death was her fault.

White, better known by her nickname Cindy, grew up in Greenwood, although she spent part of her childhood in Ladoga, a small town south of Crawfordsville. She was the second oldest of Earl and Emma White's six children. He'd worked as a construction laborer, while she stayed home and struggled with alcohol abuse.

White longed to be a daddy’s girl — and from outward appearances, she was. Her father took her on frequent truck rides he dubbed their "special time." For years, she kept what happened on those trips to herself. It began with fondling when she was 8, White alleged, and escalated to painful intercourse as she got older.

After learning in a sex education class at school the things her father was doing to her were wrong, she mustered the courage to tell her mother. She picked a time when they were alone together at a laundromat. After revealing her secret, her mother slammed down the washer’s lid, White recalled. Then her mother ordered her to never bring it up again.

"I was hurt. My feelings are still hurt," White said. "Because I was like, 'Well, who’s going to help me?'"

After her father died, the family moved to Greenwood, where Emma White spiraled deeper into alcoholism.

The case of Sarah Jo Pender: 'I deserve to be let home,' Pender said. The man who prosecuted her agrees.

"She got to the point that all she did was sit on the couch and drink beer from morning until night," White said. She remembers taking her mother’s government checks and cashing them to buy more beers at her orders.

The abuse did not stop, White said. She claimed another male relative also had been sexually assaulting her even before her father died. She said those assaults were even more violent.

"Anytime I would refuse," she recalled, "he would beat me."

White, again, reached out to her mother for help. This time it was during a visit to her father's gravesite.

"Mommy, I need to tell you something," she told her. "You know what Daddy did to me? … (he) is doing the same thing."

White said her mother berated her. She called her a "piece of trash" for sleeping with her husband and, now, another man. On the drive home, Emma White stopped the car near a railroad crossing. She locked the doors, White said, then threatened to drive into the path of an oncoming train.

"She said, 'I'm going to just sit here and take us both out,'" White recalled. "I was like, 'Please don't, let's go. I'm sorry. I won’t say nothing else, please.'"

Kathleen Cerna, White's younger sister, said she witnessed and also experienced sexual abuse from the male relative. IndyStar is not naming the relative because he has not been charged with a crime. He denied the allegations.

Cerna, though, has different memories of their father, whom she remembers as a "protector" and not an abuser. She also recalls seeing their mother drink, although she didn't realize until years later how severe the problem was.

After the incident at the train tracks, White said she resolved to never talk about the abuse again. If she’d learned anything, it was that no one, not even her own mother, would help. The decision she made as a teen would have a ripple effect on the rest of her life.

Meeting the Robersons, dreams of a normal life

As a teenager, White convinced her mother to let her deliver papers in their neighborhood. She said she wanted to help pay their bills. But really, it was an excuse to get away from the abuse at home.

White met a family who lived along her delivery route. She started chatting with the wife and playing with her children.

Charles and Carole Roberson were originally from Evansville, and sometime in the late 1960s or early 1970s, the couple moved to Greenwood along with their young children. They lived in a three-bedroom house in a modest residential neighborhood just west of the Greenwood airport. White said she spent hours there, staying until dark to avoid going home.

"I would try to be gone as long as I possibly could," she said.

The Robersons became her refuge. White would later testify that she once ran to them after a severe beating from the male relative who'd been abusing her, and the Robersons paid her mother $75 so she could stay with them for two days.

The friendly family was not the teen's only excuse to get away from home. She faked fainting spells so she would be taken to the hospital. It became a routine on weekends. Whether she was out walking or at the store, White would fall as if she had fainted. She said she did it for months ― to the point that ambulance drivers knew there was nothing wrong with her.

But on Dec. 10, 1974, there really was something wrong with White. The 17-year-old was admitted to LaRue D. Carter Memorial Hospital, a psychiatric facility in Indianapolis, after she woke up with her left leg numb and paralyzed.

Doctors diagnosed her with conversion reaction, a mental health disorder that results in pain, seizures and, in White's case, paralysis. The condition can be triggered by a traumatic event or a history of childhood abuse, although there's no evidence the latter possibility was ever explored by her caregivers.

White also was found to have impaired brain function and limited intellectual capacity, according to a summary of court proceedings prepared by her attorney. Medical evaluations cited her unstable home life, irresponsible and neglectful parents and poor academic performance.

Cutting helped relieve the emotional pain

White was still at LaRue Carter when her mother died in early 1975. According to Emma White's obituary, the 49-year-old died at St. Francis Hospital in Beech Grove after being hospitalized for 10 days.

Sarah White’s siblings moved in with their grandmother, while she remained in the hospital. Her leg gradually got better, and she regularly saw a psychiatrist who put her on medication, according to her court file. On weekends, though, she was sent back home for brief visits that she dreaded. Sometimes, she faked fainting to remain at the hospital.

When she returned from home visits, according to her attorney, White was often in worse shape than when she left. She began smuggling razor blades into the hospital to cut herself. In her mind, she said, cutting helped relieve the emotional pain from years of abuse.

"I would be a cutter," she said. "Just cut, cut, cut."

The exoneration of Leon Benson: After more than 20 years in prison, Indianapolis man exonerated in murder and set free

Dr. Patricia Sharpley, a psychiatrist at LaRue Carter, later testified that White made "non-lethal suicidal gestures," but she did not believe her to be insane.

The topic of sexual abuse never came up. She said she never told her doctors why she was hurting herself, and they never asked. Instead, Dr. Dwight Schuster later testified her suicidal gestures and fake fainting spells were a manifestation of her unhappiness at home.

White left LaRue Carter in October 1975, after 10 months of hospitalization. By then, she was 18. Instead of living with her grandmother and siblings, she moved in with the Robersons. She helped care for the kids and paid $20 a week in rent.

But the stability and normalcy White thought she'd finally found there were quickly shattered.

Cindy White on new abuse: 'I can't keep doing this'

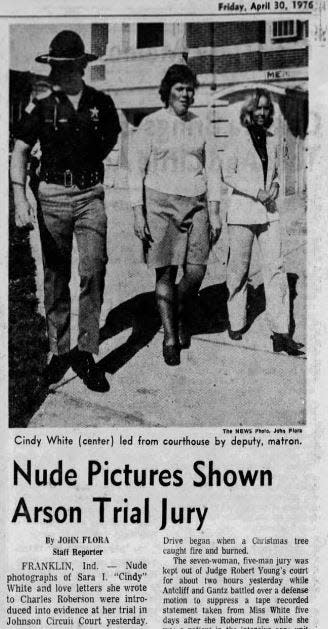

There were signs of trouble even before White moved in with the family that the immature, love-starved teen misinterpreted. Charles Roberson, in particular, began showering her with attention that crossed over to flirting. They exchanged love letters while she was still at LaRue Carter.

Suddenly, they were living under the same roof. He was more than twice her age, but the teen diagnosed with intellectual and psychiatric problems was excited about the attention. She thought she was in love.

White had always seen herself as "short, fat and dumb." She’d never had a boyfriend. But the flattery, according to her, gave way to fear and repulsion in the months she lived with the family.

White claimed Charles Roberson forced her to view pornography while his children were asleep, and his wife was at work. Their interactions escalated, White alleged, into bizarre and sometimes violent sex acts and nude photoshoots. Sometimes, she said, Carole Roberson was involved, and Charles Roberson threatened her if she tried to leave or tell anyone.

White did not talk about the alleged abuse before or during her trial. Many of the Robersons' family members have died, and IndyStar was unable to contact living relatives who are willing to comment. But Cerna, White's younger sister, would later testify at a post-conviction hearing that White had told her about the abuse.

To Cerna, she lost her sister as soon as she moved in with the Robersons. The two, who are six years apart, used to play and take long walks together, but White became withdrawn while living with the Robersons.

"I remember seeing her one day and saying ... 'You have this new family and you don't even love me anymore,'" Cerna said. "She broke down and started crying and told me that it's so far from the truth. She told me there were some things she couldn't tell me."

One day, Cerna came over to the Robersons and tried to convince her sister to leave with her. White told her she couldn't. And then, she revealed why. She showed Cerna a rubber sex device and said the Robersons were using it to abuse her.

"I tried to tell her to just leave," Cerna said, her voice breaking. "And she said she couldn't."

Desperate, White said she prayed as she tried to figure out how to escape yet another abusive situation. "God, I've got to find a way," she pleaded. "I can't keep doing this or I'm going to kill myself."

Then, as if her prayer had been answered, her sister-in-law told her about her grandmother’s Christmas tree catching fire a few days earlier. No one was hurt, but the damage forced her family to move out temporarily.

That phone conversation with her sister-in-law took place Dec. 31, 1975, and it gave White an idea.

The New Year’s Eve fire

The Robersons and their children went to bed before midnight flipped the calendar to 1976. White stayed up later, that phone call still fresh in her mind. Around 10 p.m. she turned off the TV and crawled on the couch, where she usually slept.

As she looked at the family's Christmas tree, White thought to herself: "If I set a small fire, then that’s my answer."

She envisioned the house being damaged, but insisted she never considered the possibility of anyone being hurt. Instead, everyone would be forced to move out, just like what happened at her grandmother's home. To White, it would be the ticket out of another abusive situation.

She got up from the couch and picked up a newspaper. She crumpled it into a wad and placed it behind the recliner next to the tree. And then, she set it on fire with a lighter.

Almost immediately, the house was filled with smoke, White said, and the flames spread up the wooden paneling and through the house.

White would later testify that she rushed to the master bedroom to wake up the Robersons. She tried to call the fire department, but as the operator was connecting her, White hung up because she couldn’t breathe. Panicking, she rushed to the bedroom where the older children slept. Carole Roberson was already there.

By then, White recalled, the house was completely filled with smoke. They couldn’t get out the bedroom door to escape. The only way to safety, it seemed, was the window. White said Carole Roberson told her to climb on the kids’ top bunkbed, open the window and climb down so she can hand the kids to White.

White managed to get out, according to her trial testimony, and started reaching for the boys. But that was the last time she saw anyone from the family alive.

The next thing she remembered, White said, she was lying on her stomach thinking it was all a bad dream.

Greenwood police chief: 'Handle this as a homicide'

Lynn Coon first saw flames shooting from the Robersons’ big front window. Then, she saw White coming from around the side of the house. Her face was burned, and her hands were black.

"She was screaming … she was just hollering to try and help her to get 'em out,'" Coon testified in court.

Police officers and firefighters restrained White as she screamed over and over, "Get them out, there’s other people in there, get them out," Phillip Wayne Hommell, of the Greenwood Police Department, testified.

Lt. Junice Moran, who was off duty that night but came to help, saw the fire from a mile and a half away. Greenwood Fire Chief Dick Van Valer arrived at 10:55 p.m., seven minutes after the alarm came in. By then, flames were shooting 30 to 40 feet into the air.

"It was a conflagration of the entire house," he testified.

The family’s bodies were found that night in various locations in the house. All seemed to have tried to get out. Charles and Carole Roberson, ages 45 and 41, respectively, died of smoke inhalation. So did 7-year-old Michael, 6-year-old Dale, 5-year-old Gary and the youngest, Rita or "Sissy," who was 4.

White’s face, arms and hands were covered with second- and third-degree burns. Her forearms were so badly burned that doctors gave her a shot of painkiller while they removed the scorched flesh, according to court records.

That night at the hospital, White kept asking how the children were, according to Jane Testa, a nurse at St. Francis Hospital.

"That’s mostly what she said most of the night," she Testa testified.

White remembers being told everyone was fine. She remembers going to sleep, thinking they'd all made it out safe. When detectives later visited her in the intensive care unit, where they had to wear masks and hospital gowns, White again asked about the family.

She'll never forget what one of the officers said: "Cindy, they all died."

Investigators initially thought the fire may have been caused by faulty Christmas tree wiring. But court testimony from Greenwood police officer Alan Clark revealed police suspected foul play almost immediately.

Less than an hour after the fire started, Ed Stephens, whose term began that midnight of 1976, gave one of his first orders as Greenwood police chief.

"Something does not appear right here," Stephens told Clark. "Something’s wrong. Handle this as a homicide."

To read the conclusion of this story, please click here.

Contact IndyStar reporter Kristine Phillips at (317) 444-3026 or at kphillips@indystar.com.

This article originally appeared on Indianapolis Star: Sarah 'Cindy' White: Longest-serving woman held in Indiana prison