Jupiter's moon Europa may shoot liquid water into space

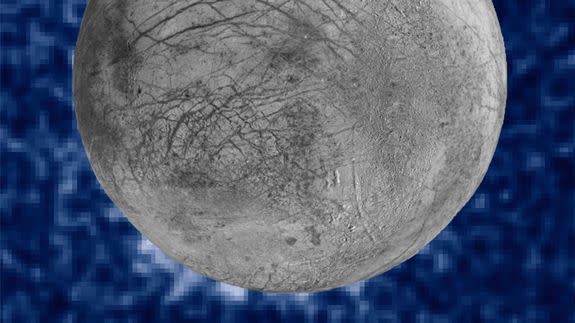

The high-powered Hubble Space Telescope has caught sight of something amazing on Jupiter's icy moon Europa, NASA announced today.

Scientists using the Hubble have discovered more evidence that plumes of water spurt out of the moon's surface from its possible ocean below.

If confirmed, the existence of the water plumes could make it easier than expected for NASA to get a taste of Europa's alien sea, one of the most likely places in the solar system for alien life.

SEE ALSO: 3 facts and 1 big question about Jupiter's icy moon Europa

"If there are plumes emerging from Europa, it is significant because it means we may be able to explore that ocean of Europa for organic chemicals or even signs of life without having to drill through unknown miles of ice," astronomer William Sparks, who helped make these Hubble observations, said during a press conference Monday.

The Hubble observations show that the possible plumes — which were spotted three different times in 2014 over the course of 15 months — shoot as many as 125 miles into space before raining back down onto Europa's surface.

Image: NASA

Scientists still aren't sure if the plumes appear with any kind of regularity on Europa or if they shoot forth randomly, but more observations with the Hubble or NASA's future James Webb Space Telescope mission could help pin down the exact timing of the water plumes.

Sparks does caution that it's possible Europa isn't erupting with plumes of water vapor, saying that "the observations are at the limit of what Hubble can do," and that the observations might be due to some kind of observational mistake.

In spite of that caveat, however, the results are compelling, lending credence to earlier evidence of plume activity.

Mission to Europa

Europa has long been considered a good place to go hunting for alien life in the solar system.

The moon's presumably huge ocean of liquid water, warmed by the stretching and straining exerted on the world by Jupiter's immense gravity, may be home to microbial or other forms of life.

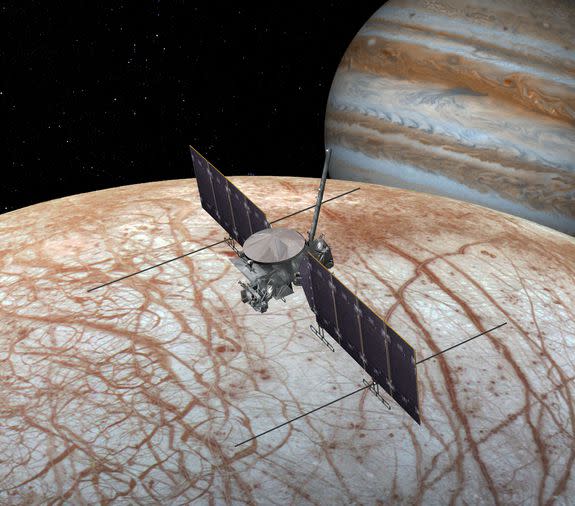

NASA is planning on launching a spacecraft to Europa sometime in the 2020s.

The flyby mission would give scientists a better sense of what the moon's surface looks like, possibly spotting some of these plumes of water from a close distance and helping researchers understand whether the moon is habitable.

Missions to Europa in the far future could also be aided by the existence of these plumes of water and ice particles. A lander could conceivably sample the ocean by snagging and analyzing some of the water shooting from a plume, instead of sending a submersible deep down into the ocean, which would be a far more complicated mission.

Not a first, but still exciting

Image: NASA

While this result is exciting, it's also an incremental finding. The Hubble has seen hints of these plumes before.

In 2012, another team of scientists using the telescope got a tantalizing look at the plumes in the south polar region of the moon.

Both teams used different methods for finding evidence of the plumes, though they haven't yet made observations of them simultaneously.

"The estimates for the mass [of the plumes] are similar, the estimates for the height of the plumes are similar," Sparks, an author on a study detailing the new plume finding in the Astrophysical Journal, said in a statement. "The latitude of two of the plume candidates we see corresponds to their earlier work."

If Europa's jets are confirmed, it also won't be the first icy moon to be found with plumes of water shooting from it.

Saturn's moon Enceladus also has plumes of water coming from its surface. The Cassini spacecraft, which has been exploring Saturn and its many moons for more than 10 years, actually got a little sample of one of those plumes in 2015.