Are Julian Assange and WikiLeaks essential or criminal? After all, hacking is theft.

As an investigative reporter, I strongly believe in the importance of transparency in government, accountability of public agencies and full disclosure of acts taken in the name of the American people. I believe secrets to protect national security, though necessary, should be rare and reviewed often to prevent cover-ups and corruption. To me, whistleblowing at the risk of one's job or going to jail, to expose undisclosed waste, fraud or abuse, promote social justice and/or protect the public interest, is an act of heroism.

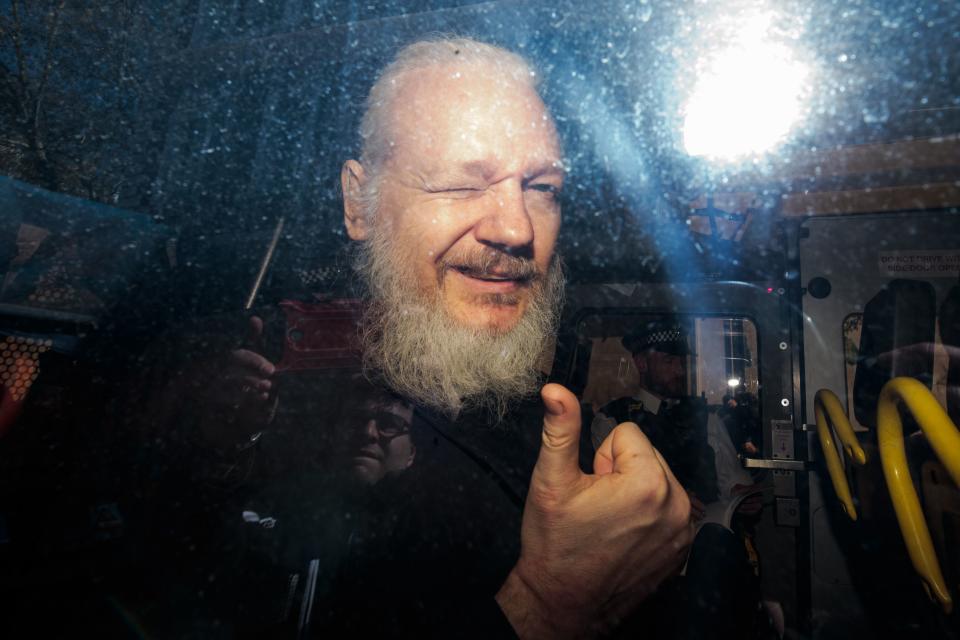

Hacking is a method, not a philosophy. Hackers deconstruct bureaucracies to see where they are weak or redundant and exploit systemic vulnerabilities. Julian Assange, the world's most infamous hacker, uses the principle of the people's right to know to justify digital breaking and entering. The line between transparency and trespassing is a moving target and the WikiLeaks founder knows something about both. Until last Thursday, he had been hiding out to avoid prosecution by Sweden and the U.S. government for more than six years under the increasingly unwilling hospitality of the Ecuadorian Embassy in London. He was evicted and dragged out by Scotland Yard and will now presumably be forced to defend his argument.

Read more commentary:

WikiLeaks founder Assange will be punished for embarrassing the DC establishment

Julian Assange deserves a Medal of Freedom, not a secret indictment

Spygate: Did American intelligence agencies spy on Trump? Barr says we'll find out.

It will be a tough call. Prior to my career in journalism, in the pre-digital 1980s, I was a private detective. Those days were during the wild west of information retrieval. My bag of tricks included telephone pretexts, an analog form of hacking, to extract information from unwitting gatekeepers.

My clients were law firms, businesses, nonprofits and journalists, who always had a specific agenda that they hired me to achieve. My cases sought substantiation of suspected anti-competitive practices, bid irregularities, product liabilities, political corruption and housing or employment discrimination. The value of documented evidence is to impact one's goal and I believed their goals were worthy of the effort.

A terrible person who disclosed valuable info

All that high-minded self-regard notwithstanding, as privacy rights and information security abuses by others gained public attention, I had my own consciousness-raising epiphany. I stayed away from using misleading omissions and making obscured representations. Instead, I developed inside sources, who knew exactly who they were talking to. I was prepared to testify or sign affidavits detailing how I'd come to whatever knowledge I gained.

If access to information is the coin of the realm, authorized entry is the gold standard. By the early 1990s, I was on the government payroll as a US Senate investigator. My inquiries were backed by seldom invoked, though always implied, subpoena power. My phone calls were returned without need of subterfuge.

Today, watchdog organizations and investigative reporters navigate a field of anonymous tips, keystroke counted redactions, dark web denizens, encrypted communications, purloined passwords and a few trusted truth-tellers to bring sunlight to information.

Although Assange sounds like a terrible person on many levels, back in 2010 when he posted hundreds of thousands of digital files disclosed by then-PFC Bradley Manning documenting excesses by the U.S. military in Iraq and Afghanistan, and an enormous cache of State Department cables, I gave him a nod of respect for injecting the skies full of sunshine for open government. Embassy cables are a great way to learn about U.S. foreign policy.

Whistleblowers are the real heroes

While whistleblowers continue to fight an uphill battle to make claims of wrongdoing, my ambiguity about hacking in general, and WikiLeaks in particular, is apparently shared by some of its direct beneficiaries. When First Amendment champion The New York Times ran the sensational stories drawn from the very act for which Assange is now indicted (and for which whistleblower Manning — now Chelsea — spent years in jail), the newspaper of record's editors admitted their squeamishness about revealing the contents of the hacked files: "When we find ourselves in possession of government secrets, we think long and hard about whether to disclose them."

Perhaps reluctant to give Assange the legitimacy a Pulitzer might have imparted, the Times eschewed submitting its scoop for the prize.

As a former private sleuth, past congressional staffer and investigative reporter, my sympathies toward the WikiLeaks founder are just as conflicted. Assange is a toxic house guest and alleged sexual assailant. He is not a journalist, but his published files gave media outlets valuable material important for Americans to know. He is not a political operative but his posting of Russian hacked emails of Democrats helped secure the presidency for Donald Trump. And while he has given whistleblowers a platform to reveal abuses, he is not a hero. He is a secrecy vandal.

Bonnie Goldstein, a former private aU.S. Senate investigator and network TV producer, is a writer in Washington, D.C. Follow her on Twitter: @kickedbyanangel

You can read diverse opinions from our Board of Contributors and other writers on the Opinion front page, on Twitter @usatodayopinion and in our daily Opinion newsletter. To respond to a column, submit a comment to letters@usatoday.com.

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Are Julian Assange and WikiLeaks essential or criminal? After all, hacking is theft.