John Lewis Knows That Look in the Eyes of Trump Supporters

Congressman John Lewis (D-Georgia) is a Civil Rights icon and a Mt. Rushmore-worthy American hero. At the dawn of the Civil Rights Movement, Lewis marched fearlessly into the maws of the Jim Crow South, through angry, racist mobs and truncheon-wielding state troopers, armed with nothing more than the courage of the righteous and unconditional love in his heart. Lewis shed his own blood to shame this country into living up to its founding promise that "all men were created equal." This remains a work in progress.

At 76, he is the last man alive who spoke at the March On Washington in 1963. He is the last of the so-called Big Six-the six leaders of the Civil Rights Movement shepherded by Martin Luther King Jr.-and as such he is the closest thing we have to an American Gandhi still standing. Two weeks ago, Lewis was awarded the Liberty Medal at the National Constitution Center on Independence Mall in Philadelphia, the cradle of American democracy. Previous recipients include the Dalai Lama, Nelson Mandela, Mikhail Gorbachev, and Muhammad Ali.

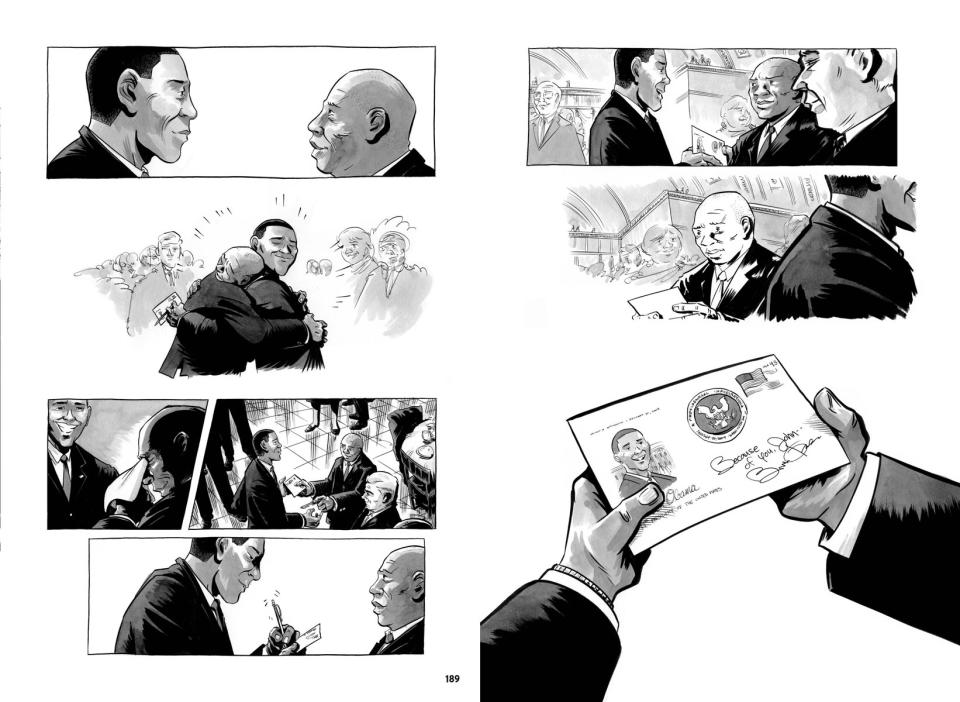

His remarkable journey from chicken-tending son of a sharecropper to 15-term United States Congressman is told in a gripping 600-page three-part graphic novel called March. The trilogy documents Lewis' central role in the white knuckle saga of the Civil Rights struggle-fraught with intolerable cruelty, daily indignities, appalling ignorance, and unspeakable violence-which is bookended by the inauguration of Barack Obama in 2008. March does not sanitize the brutal realities of the struggle, nor does it shy away from spelling out the N-word, which was hurled at Movement activists with shocking regularity by everyone from JFK-appointed federal judges on down to toothless backwoods Dixie thugs. "We wanted to make sure the story was told in an accurate and unflinching way," says Nate Powell, who illustrated March.

March does for the Civil Rights struggle what Art Spiegelman's Maus did for the Holocaust: shine a light on the darkest corners of the history of the 20th century-when the human race collectively realized it had reached the outer limits of its own humanity and stepped back from the abyss-rendering it knowable, and thereby unrepeatable, for children of all ages, in perpetuity. The second installment of March won the Eisner Award, which is like the Pulitzer Prize of comic books, and the just-published third and final installment has been nominated for the prestigious National Book Award. To date, school districts in over 40 states have adopted March as part of their core curriculum. Going forward, every 8th grader in the New York City school system will read March as part of their study of American history.

The kernel of the idea for March came from Lewis' youngest aide, Andrew Aydin, a self-described comic book nerd who worked his way up from the mail room to become the congressman's policy advisor and digital director. When the idea was first broached by Aydin in 2008, it was scoffed at by senior members of Lewis' staff. But Lewis was intrigued. "Don't laugh," he said, pointing out that as a young man he was inspired to join the Civil Rights Movement by a comic book called Martin Luther King and the Montgomery Story. "I read the Martin Luther King comic and started studying the way of peace, the way of love, the philosophy and discipline of nonviolence, and I finally said yes to Andrew, if he did it with me," Lewis told me.

From the beginning, the intent of March was to use Lewis' inspirational life story to try and solve The Nine Word Problem. "The vast majority of students graduating from high school only know nine words about the Civil Rights Movement: Rosa Parks, Martin Luther King, and I Have A Dream," Aydin says. "Our goal was to defeat The Nine Word Problem because you can't understand the politics of today without understanding the Civil Rights Movement."

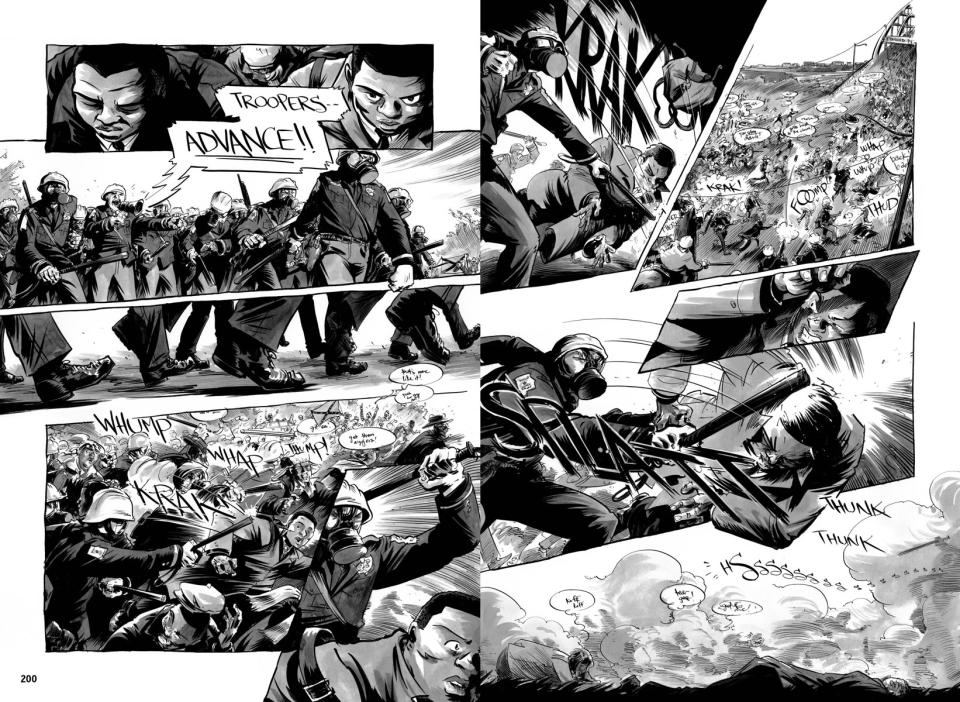

Lewis has proven to be an effective and enthusiastic evangelist for March, routinely traveling to readings on weekends with Aydin and Powell to far-flung mom-and-pop comic books stores across the country. This summer at Comic-Con in San Diego, he donned a raincoat and backpack like he wore that infamous day in 1965-when he marched across the Edmund Pettus Bridge and an Alabama state trooper cracked his skull open-and led a merry march of conventioneers, zigzagging in between befuddled furries and trekkies and bronies. A few weeks ago on Late Night With Stephen Colbert, at the typically ludicrous behest of the titular host, Lewis crowd surfed over the heads of the audience at the Ed Sullivan Theater in New York.

"It's been an unbelievable ride, really, to see the response, the reaction of people all over America," Lewis says. "It's important for our young people and generations yet unborn to know what happened and how it happened, how we've made the progress that we've made. The story of the Civil Rights struggle is the story of America."

Below are six pages from the the third and final installment of March, including new insights from Lewis.

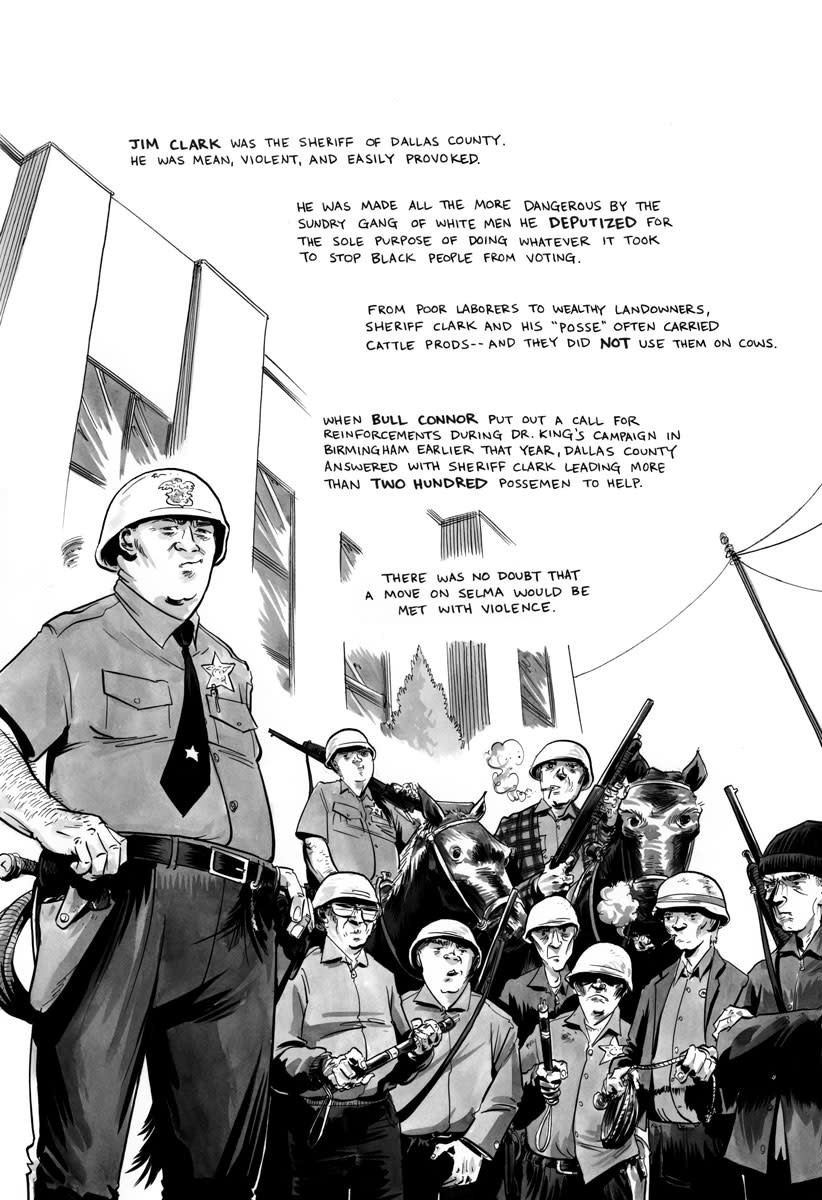

"When I see the people that react to Donald Trump's words at those rallies, I see the same look in their eyes that I saw [in the eyes of Sheriff Clark and his posse]-a look that says, 'you're not a part of us, you're not a part of the American family, you come from someplace else.' When Trump talks about building a wall, to lock certain individuals out, people rallied. They screamed and yelled. It reminded me of some of the rallies that I saw on television for [infamous racist/segregationist Alabama governor] George Wallace during the '60s. It makes me somewhat sad. I thought for many, many years that our country had become much more hopeful, much more optimistic, and we had come to a place where we saw unbelievable changes. I've said over and over again that we have witnessed what I like to call a nonviolent revolution in America during the last 50 years, a revolution of values, a revolution of ideas. I think the Trump campaign is trying to take us back to another place, another time, and we've come so far, made so much progress, I don't think we can afford to go back. We have to go forwards, and continue to be what Dr. King called 'the beloved community,' where we lay down the burden of division, the burden of hate, and create an American community at peace with itself."

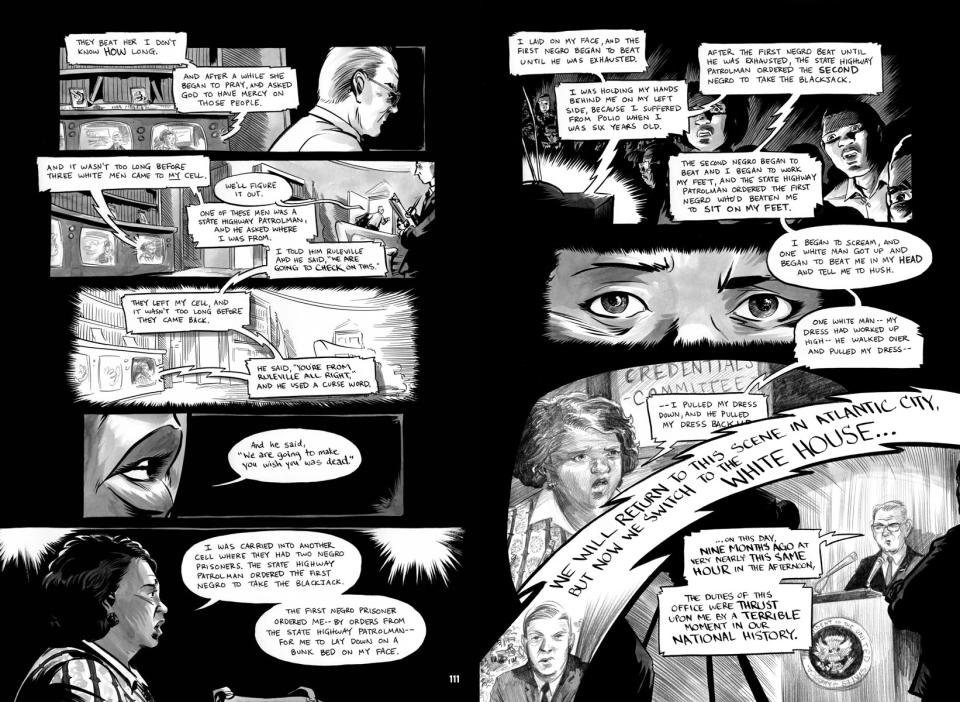

"In the early 1960s, black people in the American South lived in constant fear, they were afraid. There were people afraid to come to the mass meetings, to come to the rallies, so we had them in the churches where people felt safe, we heard people saying, 'People are meeting in the church, it must be alright.' Then they started burning down the churches, but people still came out. Those of us, as part of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, the core of the young people, the students, we lost that sense of fear. I know I lost that sense of fear, and we didn't know when we would be beaten, when we would be left bloody and unconscious. They would single out the white participants for especially brutal treatment because they saw them as betraying the white race. On the Freedom Rides, on the march from Selma to Montgomery, we were prepared to die for what we believed in. We wrote our wills in case something were to happen to us. We didn't know whether we'd return or not."

"After LBJ became president, he became deeply committed to the cause of Civil Rights. He said, and he felt, that he had a moral obligation to get the Civil Rights Act of 1964 passed as a living memorial to President Kennedy. He did everything possible to bring together a bipartisan coalition to pass the Civil Rights Bill and he did. I've just been trying, for more than 50 years, to help. When I was growing up, as the book points out, I didn't like what I saw in rural Alabama. I didn't like what I saw when I visited Montgomery, Tuskegee, Birmingham. I didn't like what I saw as a student in Nashville. But I heard about Martin Luther King, I heard his words on the radio, I heard about Rosa Parks. I read the little comic book that sold for 10 cents, that Dr. King helped edit, and it inspired me to find a way to get in the way. When I was a boy I'd ask my mother, ask my father, ask my grandparents, when I saw WHITES ONLY water fountains, why is it like this? And they said that's the way it is, don't get in the way and don't get in trouble. But Rosa Parks and Dr. King and the Little Rock 9, who were about my age, inspired me to get in trouble, what I call 'good trouble,' 'necessary trouble,' and I've been getting in trouble ever since."

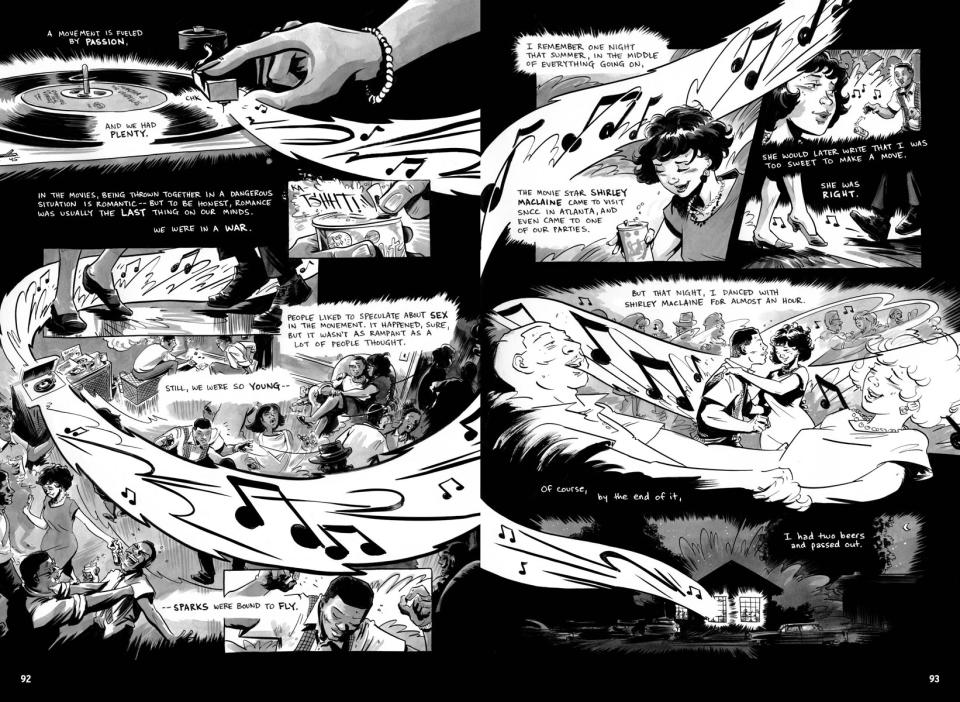

"Over the years, I heard from [Shirley MacLaine] and I would see her from time to time at different social events, during political campaigns, and at the Democratic conventions. She was deeply committed to the Civil Rights Movement and to peace and a world at peace with itself. The Hollywood celebrities were welcomed into the movement with open arms. People were glad, and pleased, to see Hollywood personalities marching with us to the march on Washington and coming to the South to lend their support, their visibility, and coming to march with us from Selma to Montgomery."

"The violence that I received, the beatings, the harassment, that happened to me, I lived to survive. Many others that were beaten, wounded, or shot and killed, they gave up their lives. I just gave a little blood here and there. I don't have nightmares or bad dreams about what happened. I'm very blessed, not just lucky, that I made it through all that. I do not know the name [of the Alabama State Trooper that fractured my skull at the Edmund Pettus Bridge]. I didn't have any contact with any of the troopers after what happened. None of them ever expressed any regret to me about what they did that day."

"Looking back on the last eight years, I believe President Barack Obama did as much as he could. He spoke out and he tried to lead the nation. He faced a tremendous amount of opposition deployed against him by the Republican Party. The very evening of his inauguration, the congressional Republican leadership met in their office in the Capital and said they would not cooperate with him. They would not support any of his proposals or legislation. They would make him a one-termer."

Courtesy of MARCH: Book Three by John Lewis, Andrew Aydin, and Nate Powell. Copyright © 2016 by John Lewis, Andrew Aydin, and Nate Powell, used by permission of The Wylie Agency LLC.

You Might Also Like