How John Franke prosecuted Frank Balistrieri and dealt a crippling blow to organized crime in Milwaukee

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

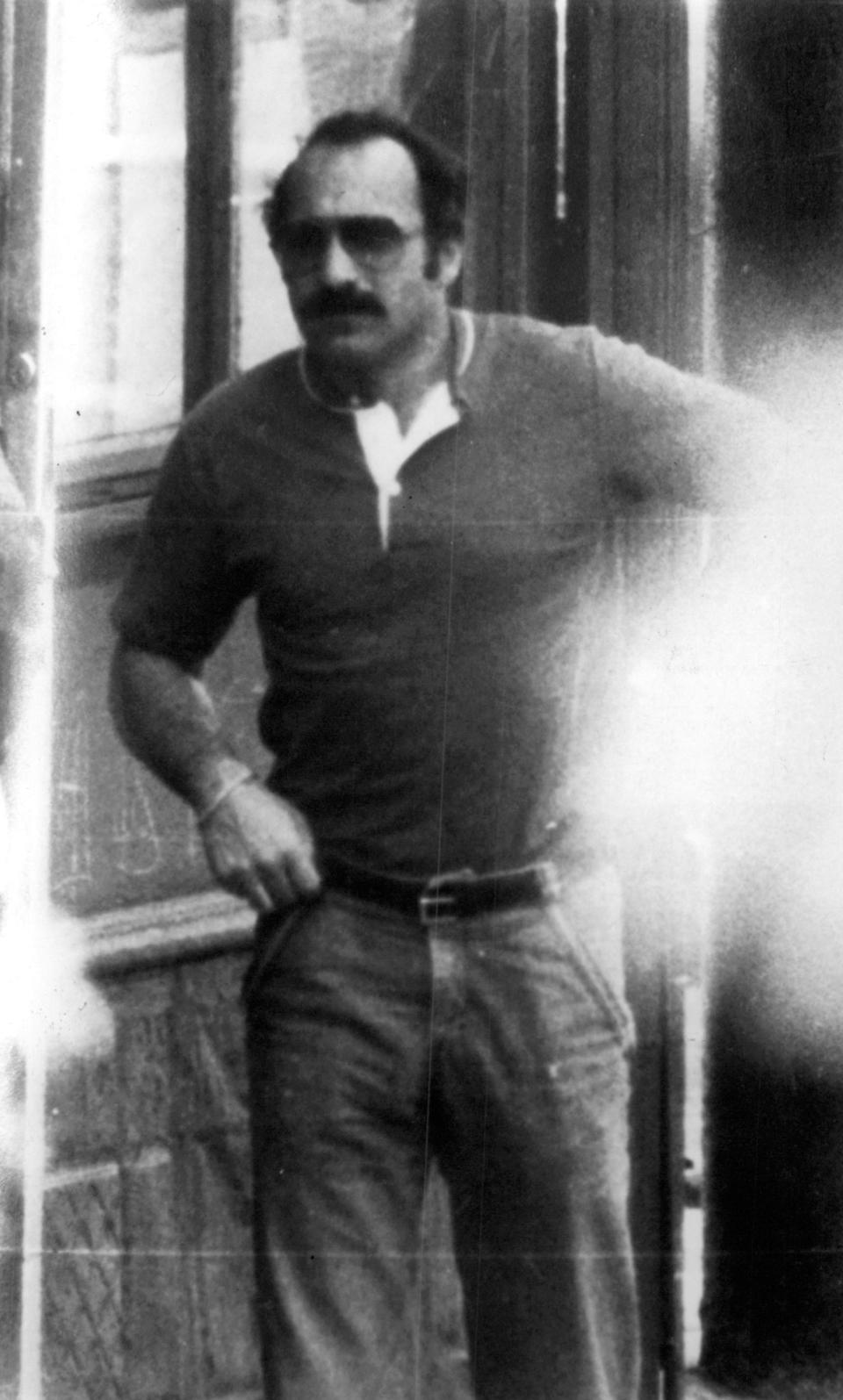

When Milwaukee organized crime boss Frank Balistrieri was facing gambling and extortion charges in the 1980s, the case against him and his associates was such major news that The Milwaukee Journal once dubbed it the "World Series of Trials."

Then-federal prosecutor John Franke, who served on the Organized Crime Strike Force for the U.S. Department of Justice from 1982 to 1987, was at the center of it all. He was the lead prosecutor in a pair of six-week trials, held in 1983 and 1984, which led to convictions for Balistrieri and a number of his associates, including his two sons.

The cases were made possible by years of work, including an FBI investigation that brought agent Joe Pistone to Milwaukee while he was working undercover as "Donnie Brasco."

For his crimes in Milwaukee, Frank Balistrieri was sentenced to 13 years in prison. Two years later, in a separate federal case involving skimming money from Las Vegas casinos, Balistrieri pleaded guilty and was sentenced to a concurrent 10 years.

The trials are widely credited with delivering a crippling blow to organized crime in Milwaukee.

Franke's work on the Balistrieri trials was featured in a recent Journal Sentinel investigation, "My Cousin Augie."

Franke, now an attorney with Gass Turek who is serving as a Milwaukee County reserve judge, spoke this week about the case during a Rotary Club of Milwaukee event at the War Memorial Center.

Below are excerpts from his speech, which have been edited for length and clarity.

His involvement began with a birthday call to his father, prominent attorney Harry Franke

My story started on his birthday — October 13, 1981. I was in my sister's apartment in Boston, drying out from a three-week bicycle trip in upper New England in which it had rained on 13 of 15 days, heavily. And after five years of working as an assistant U.S. attorney in Madison, I was taking a break to do some serious biking and think about what I wanted to do when I grew up.

We called him to wish him a happy birthday. He didn't want to talk about his birthday. All he wanted to talk about was this story: the federal prosecutor who had been working for years on the Balistrieri cases, and had just returned four indictments in early October, had suddenly resigned.

So my father, of course somewhat concerned about my career, suggested this might be a good job opportunity for me. Not to mention a chance to get me back to Milwaukee — a place I had told him I would not live or work in as an attorney, certainly not in his shadow.

Franke wanted a rematch with prominent defense attorney Jim Shellow

Balistrieri's attorney at the time was Jim Shellow, who was one of the more colorful and prominent defense attorneys of that time.

My second trial in Madison as assistant U.S. attorney was a six-week tax trial against Jim Shellow. And it was really in that moment, that trial, that I learned how much I liked being in the courtroom, how much I liked trial work, and how much I had to learn about trial work. And the thought of the rematch with Jim Shellow was indeed intriguing.

Over the next month as I traveled the coastal roads and inland roads of southern Spain, I had lots of time to think. And I kept thinking about the Balistrieri case and I kept thinking about this guy, Jim Shellow.

So I handwrote an aerogram explaining why I was the perfect guy for this job. And that if it happened still to be open when I got back, I would be very interested in it. To my surprise, when I returned just before Christmas after about two and a half months, the job was still open.

Organized crime in Milwaukee involved vending machines and sports gambling

Over many, many decades, primarily through informant information, the Milwaukee FBI had developed a pretty good picture of the Milwaukee mafia run by Frank Balistrieri, with lots of informant reports about sports bookmaking, vending machine businesses, unions, related extortion and murder.

While the Milwaukee family was in some respects viewed as under or subservient to Chicago, the FBI intelligence — this is from 1963 — had already identified Frank Balistrieri as the boss of Milwaukee and also as an independent person on what was known as La Cosa Nostra Commission.

Besides the usual rackets that any FBI investigation would worry about, there was in the background of everything they did a significant series of murders — all of which were believed to have been ordered by Frank Balistrieri, none of which were ever proven or prosecuted.

The FBI sent undercover agent Donnie Brasco to Milwaukee to infiltrate

Special Agent Joseph Pistone became "Donnie Brasco" hanging out in New York as a purported jewel thief and hoping to connect with New York mobsters. He met a Bonanno family member, a soldier named Lefty Ruggiero. And that's when things really took off in New York and ultimately connected to us here.

Joe Pistone's success in his undercover operation encouraged the FBI to undertake the rather extraordinary steps that are involved in setting up undercover operations in other cities, including Milwaukee.

And in Milwaukee, the undercover agent was a guy named Gail Tyrus Cobb, who I knew as Ty Cobb.

The FBI investigation involved Cobb posing as a new vending machine businessman

The Milwaukee office managed to sell the FBI authorities on this undercover operation in which Ty Cobb, acting as "Tony Conte," would set up a vending machine business in the hopes that a little extortion might happen.

Initially it didn't work. Nothing happened. Conte went around to known restaurants and bars that had Balistrieri vending machines trying to solicit customers, speaking to vending machine distributors. He didn't get any business, but he also didn't get any threats.

So the agent running the Milwaukee operation got the idea of trying to nudge things by having Donnie Brasco let Lefty know that he had this associate in Milwaukee who was trying to get into the vending machine business.

This had to be done very carefully. It just had to be put out there to let Lefty take the bait, and Donnie Brasco was extraordinarily good at that. He did. And Lefty did take the bait.

After this connection was made, Lefty comes to Milwaukee to check things out.

Much of the time that Lefty spent in Milwaukee was in Cobb's undercover car, which had a tape recorder in it, which was wired. And this produced endless, endless conversations, most of which was complete drivel, but occasional pieces of which were important and certainly ultimately implicated Lefty Ruggiero in his part in this extortion.

Lefty Ruggiero was 'in another world'

Lefty, he really was a fascinating guy. I've listened to his voice on so many tapes. He was an interesting mix of Yogi Berra, and something much more serious.

He could sound like such a goof. He just was in another world. One of the things I remember on the tapes was when one of the people was talking about someone getting roughed up. Lefty said, "Well, a little violence never hurt nobody."

Car bombing murder of Augie Palmisano shakes up investigators

A week after Lefty's first visit to Milwaukee, we had the murder of Augie Palmisano, which was one of the most dramatic in the series of murders. This was June 30, 1978. His car blew up and he was killed.

And from that point on, Tony Conte, the undercover agent, got a remote starter for his car.

This played into Lefty's hands beautifully, because he could point this out as an example of why Tony Conte needed Lefty's protection, why he was the guy who would give him protection. All he had to do was give him some money and cooperate.

Balistrieri's comments at a meeting provided evidence for extortion charge

Lefty's networking resulted in the critical sit-down, which ultimately produced the evidence that allowed us to bring the extortion charge.

According to Cobb's report, Frank points to him and says, "I know all about you. You bought three (vending) machines, paid cash. You got a place on the Farwell that's been empty. We figured you was the G. They told me you were a tall, good-looking fellow, well-mannered, moving into the vending machine business right here in the middle of my town, right in my block. That's why we were looking for you."

Frank then turns to Lefty and says, "We were going to hit him."

And really without that conversation, and Cobb's credibility in relating the conversation, we wouldn't have had a case.

The wiretap also caught Balistrieri associates joking about murders

In the (wiretap) tapes, Joe Balistrieri (Frank's oldest son) is heard to say, "(FBI agents) made Sam Librizzi write the following names: Louie Fazio, Augie Maniaci, Augie Palmisano, Vince Maniaci. What is this, the hit list?"

And then there's laughter, and the laughter is utterly chilling. Laughter can speak loudly, and in this case it really did.

Joe Pistone was a star witness, and closely guarded for his safety

I can tell you that you don't get a witness like Joe Pistone very often in life.

The jury just ate up whatever Joe Pistone told them.

I had to spend a lot of time with both of these guys (Pistone and Cobb) in preparing for trial. There were at least four prep sessions — and at that time, Joe Pistone was one of the most heavily guarded people in America, it seemed. I would not know where I was going until I got to the airport gate with the FBI agents I worked with. Then when I saw the gate, I would know where we were going.

We met in Nashville, San Diego, Tampa, and then closer to trial preparation, we met at Lake Lawn Lodge.

Did Frank Balistrieri get away with murder?

As I have looked back over this, I have wondered — did we ever have enough to prosecute any of these murders? The decision had been made before I had gotten in there not to, but additional evidence was gained through the course of the investigation.

There were tantalizing references by Frank to any number of these murders on the various wiretaps that were ultimately done. When Frank says "Five times 38," the FBI believes he was talking about the Louis Fazio death. (Fazio was repeatedly shot with a .38-caliber.) The tapes had these tantalizing quotes, but nothing that would really constitute proof beyond a reasonable doubt.

We have Tony Conte's report, just about a month after the murder (of Augie Palmisano). He's sitting down with Frank Balistrieri, and Frank's talking to this group of people — about eight people around the table — and in reference clearly to Augie Palmisano, Frank says, according to the report, "He called me a name to my face, now they can't find his skin."

The case came with a 'tremendous' sense of responsibility

The thing I remember most feeling, I guess, was the sense of responsibility. So much of it was personal to the agents with whom I spent so much time — what they had done, and the risks that they had taken. This was years of work, and years of risk on Donnie Brasco's part. So there was a tremendous sense of responsibility.

When you're in the throes of litigation and the throes of trial, you just move in the day to day and night to night, and you don't really think about that until it's over. But I do remember carrying a real sense of responsibility for what I was being asked to do. And I did the best I could.

Contact Mary Spicuzza at (414) 224-2324 or mary.spicuzza@jrn.com. Follow her on X at @MSpicuzzaMJS.

This article originally appeared on Milwaukee Journal Sentinel: How John Franke prosecuted Frank Balistrieri in Milwaukee in the 1980s