What Joe Biden Got Out of Anti-Busing Politics

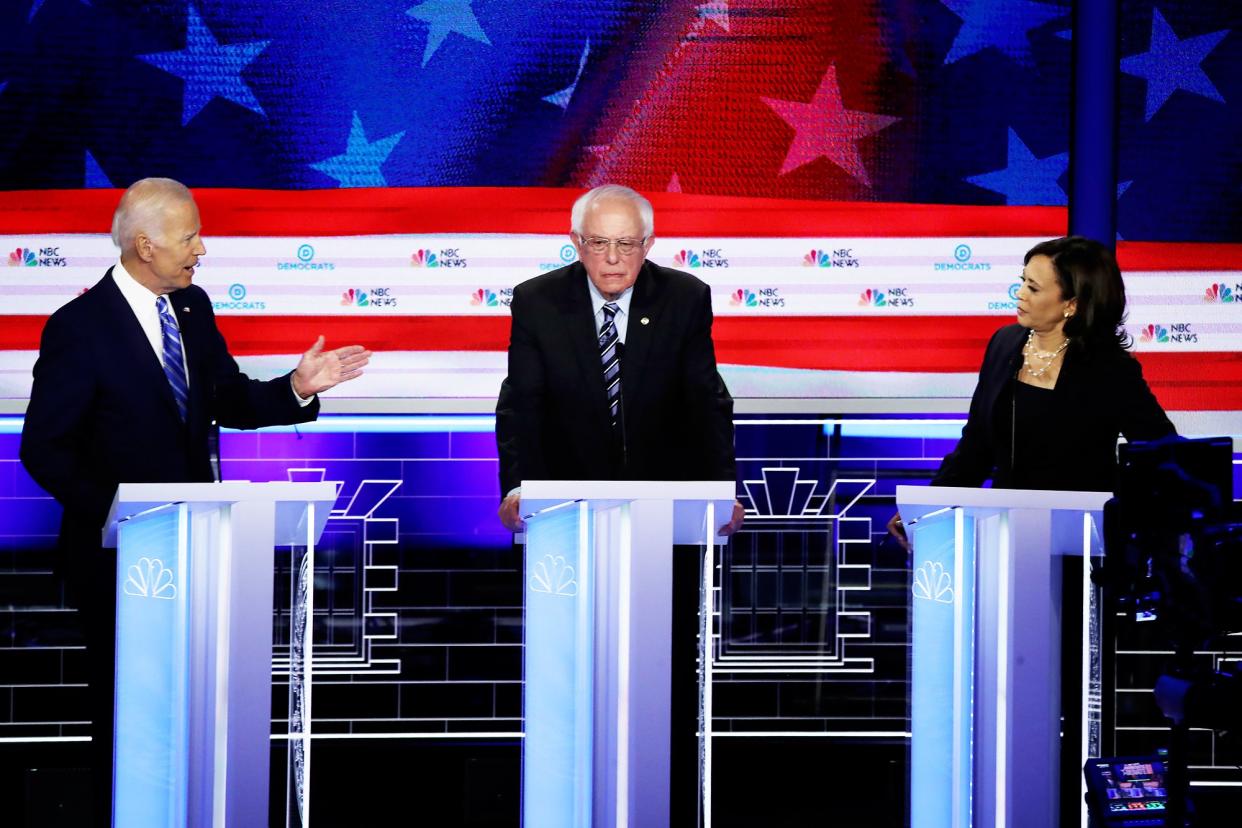

Lately, former vice president Joe Biden has encountered sharp criticism for his nostalgia over his early days in the Senate. Praising the collegiality of the 1970s, when liberals like Biden and Ted Kennedy could cooperate with white supremacists like Mississippi senator James Eastland, Biden chastised current politicians for their ideological purity and rigidity. “We got things done” then, he proclaimed of those bygone days at a recent fundraiser. Until Kamala Harris’s targeted critique in Thursday night’s Democratic debate, some outraged commentators have failed to ask what, precisely, Biden got done working with James Eastland and company.

One thing he got was a seat on the Judiciary Committee, which was chaired by Eastland. Another was support for legislation so important to Biden that he returned to it repeatedly: laws restricting federal support of school desegregation.

It is hard to exaggerate white opposition to busing schoolchildren in the late 1970s, when Biden teamed up with, among others, Kansas senator Robert Dole and James Eastland to contain the role of the federal government in implementing it. In 1976, Wilmington, the largest city in Biden’s home state of Delaware, was under court order to desegregate its school—22 years after Brown. Throughout the course of the 1970s, Biden supported the anti-busing legislation of others and introduced some of his own.

Two separate but complementary issues characterized school desegregation efforts when Joe Biden took his seat in the Senate in 1973: how to end discrimination resulting in segregated schools, which had been declared unconstitutional in Brown, and how to promote integration, which was not constitutionally mandated but commonly considered a beneficial effect of desegregation. Everyone agreed that Brown called for desegregation of public schools: but how?

The burden fell on the federal courts. Until 1969, everything the courts tried was stymied in the South by white resistance, including violence, the wholesale desertion of public schools for private all-white “segregation academies,” “white flight” across urban and country borders, and foot-dragging by state legislatures and municipal governments. In Alexander v. Holmes County Board of Education (1969), an exasperated and unanimous Supreme Court, led by Chief Justice Warren Burger, Richard Nixon’s first appointment to the Court, ordered 33 school districts in Mississippi to desegregate their schools “now”—ending the delays occasioned by Brown II’s requirement of “all deliberate speed.”

After Alexander, small towns had little choice but to desegregate. Bigger cities, though, managed to maintain what were effectively dual systems of neighborhood schools based on segregated residential patterns. Then, in Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education (1971), a unanimous Supreme Court endorsed the practice of assigning students to particular schools, even if the schools were not the closest to their homes, in order to desegregate school districts whose policies intentionally perpetuated segregated schools across district lines. This process came to be known as “busing.” These decisions, along with the 1964 Civil Rights Act, which authorized the Department of Health, Education and Welfare (HEW) to withhold federal funds from segregated school districts, finally broke the back of school segregation in the South.

The North was another story. Busing was overwhelmingly opposed by whites, and their resistance was often as fierce as it had been 15 years earlier in the South. When a Detroit judge ordered busing in 1974, Mothers Alert Detroit (MAD) attacked the busing mandated by the decision. Not to be outdone, angry white mothers in Boston formed ROAR, an anti-busing organization that pledged to “restore our alienated rights.” Both claimed to oppose busing rather than desegregation. Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) founder and Georgia congressman Julian Bond was skeptical, commenting wryly, “It’s not the bus, it’s us.”

It did not take whites long to figure out that the best way to liberate themselves from desegregation was to abandon the cities and move to the overwhelmingly white suburbs. This avenue of escape was cut off briefly in 1974, when a federal judge ruled that school district lines were “simply matters of political convenience” and ordered busing between Detroit and its suburbs, but this solution was short-lived. The Supreme Court rejected this approach in Milliken v. Bradley (1974), ruling five-to-four that busing was inappropriate if school segregation was due “entirely” to private residential choices.

After Milliken, whites could escape urban school desegregation by abandoning the cities. “White flight” had devastating consequences for urban blacks and Hispanics, because as wealthier whites moved to the suburbs, urban schools were left with less tax money to spend per student. In a bitterly divided decision in San Antonio v. Rodriguez (1973), the Supreme Court held that such disparities in school funding did not violate the Constitution because they were not intended to harm blacks and other racial minorities and because there is no constitutional right to an equal education. Had this decision gone the other way, there would be funding parity across school districts even if whites refused to participate in desegregation.

Busing was and remains controversial among whites. A 1972 Harris Survey poll reported that a sizable majority of Americans was “willing to defy court orders on school busing.” Biden was following, not leading, his white constituents on this issue. Still, it was disheartening to hear him insist, as he did last week in Miami, that he didn’t oppose busing per se, just busing mandated or funded by the federal government. This “localism” argument has deep roots in American race politics—indeed, it was one James Eastland and his ilk returned to repeatedly.

There is good evidence that busing worked—or, it did not fail. A large decline in school segregation began in 1964 and accelerated after 1968. After peaking in the late 1980s, there has been significant backsliding, especially in the North and West. Piles of evidence document the importance of resource allocation, if not people reallocation, to the successful desegregation of public education. Federal incentives for school integration made a difference, as did a Justice Department dedicated to carrying out the directives of the courts. Overturning Rodriguez and re-instituting the financial incentives for school integration that fueled desegregation in the 1960s and early 1970s could make a big difference today.

One wonders if a President Biden would be open to this.

Jane Dailey is a professor of history at the University of Chicago and the author of several books, including the forthcoming Sex and Civil Rights: The Fight for Full Equality in Jim Crow America.

Originally Appeared on GQ