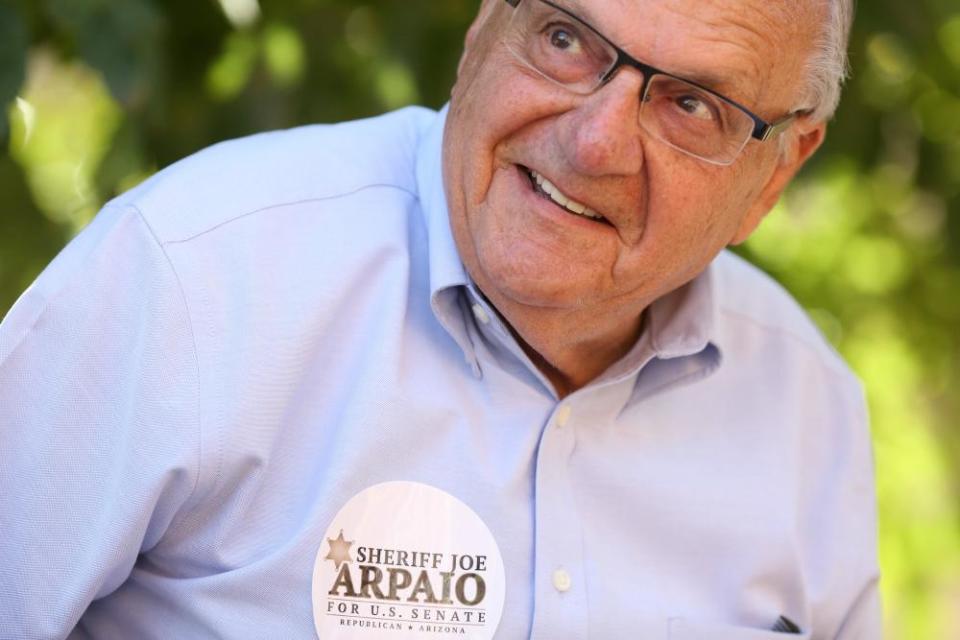

Joe Arpaio, Arizona's maverick former sheriff, faces end of political road

The 86-year-old hardliner had much in common with Trump, who pardoned him, but trailed in third in the Senate primary

Joe Arpaio, the former sheriff of Maricopa county, liked to say he had never lost a Republican primary. On Tuesday, that changed.

The 86-year-old, once a symbol of Arizona’s hardline stance on illegal immigration, finished last in a three-way race for a Senate nomination in Arizona. In Maricopa county, where he was sheriff for nearly a quarter-century, he received less than 18% of the vote.

It was an unceremonious end to the 60-year law enforcement career of a man who called himself “America’s toughest sheriff”, and who brought reality TV stunts and anti-immigrant tactics to national prominence long before Donald Trump, his political soulmate, arrived on the scene.

“He has done so much harm – hate politics, dividing families, targeting the most vulnerable,” said Alejandra Gomez, a co-executive director of the advocacy group Living United for Change in Arizona, who was a part of “Bazta Arpaio”, an immigrant-led effort to oust him from office in 2016.

“It took the people he targeted rising up against him to show his powerlessness,” Gomez said. “We stopped being afraid and we took his power.”

Arpaio became sheriff of Maricopa county in 1993. He opened the notorious “Tent City”, a jail he once joked was comparable to a concentration camp and which was closed last year. He forced inmates to wear pink underwear, work on chain gangs and endure temperatures of 120F (49C). As he did so, he racked up lawsuits that alleged harassment, neglect and even death in his jails.

But it was his approach to illegal immigration, in the later years of his career, that catapulted him to national fame. Arpaio embraced a federal program that effectively allowed his deputies to act as immigration agents. As he conducted workplace raids in prominently Latino neighborhoods, he invited camera crews along.

His wild ride came to an end on election night 2016, when he lost his seventh bid for Maricopa sheriff even as Trump, who made cracking down on illegal immigration a campaign issue, won the presidency.

Arpaio left office in January 2017. Months later he was convicted of criminal contempt of court, for violating an order to stop discriminating against Latinos. Then he received a presidential pardon, for his “years of admirable service to our nation”. Buoyed, he entered the race to replace the retiring senator Jeff Flake, a persistent critic of Trump.

Arpaio remains something of a folk hero among conservatives who thrilled to his “law and order” message and brazen policing tactics. But in the end, even his supporters came to believe his best years were past.

“I mean no disrespect – I love the guy,” said JD Hayworth, a former congressman who supported his primary opponent, Kelli Ward, a former state senator who has long taken a hard line on immigration. “I just don’t think this [was] the best time for him to field a campaign.”

In a two-hour interview at his Fountain Hills office earlier this year, Arpaio struggled to articulate a policy platform beyond unwavering support for Trump. His pitch to voters was that he would serve only one six-year term, coinciding with the end of what would be the president’s second term in office.

Surrounded by framed photographs taken with the president, Arpaio rambled about biased judges, political witch-hunts and the Obama justice department. Years after he spent county money to send a deputy to Hawaii to investigate Barack Obama’s birth certificate, he insisted he had proof that document was forged. He angrily – and repeatedly – denied harboring racial animus.

Arpaio said he never had a hero, until he met Trump. In both rhetorical style and approach, the men are strikingly alike. They were born on Flag Day – 14 June – 14 years apart, a fact Arpaio loves to share. They are both showboats, obsessed with media attention and illegal immigration. They even have a similar elliptical way of speaking.

“I hired 150 greencards,” Arpaio said, in a circuitous response to a question originally about healthcare.

But while Trump sits in the Oval Office, he is out of a job.

He lost the primary to Ward and Martha McSally, a former air force fighter pilot. McSally won every county in the state – with the exception of one along the border, which went to Arpaio.

Asked this week if he wished he had done anything differently in the campaign – or in his career, the former sheriff quoted his favorite song, Frank Sinatra’s My Way.

“Regrets, I’ve had a few,” he said. “But then again, too few to mention.”

‘Arizona is ahead of the rest of the country’

Joseph Garcia, the director of the Latino Public Policy Center at Morrison Institute, said Arpaio and Trump’s diverging political fortunes were a reflection of Arizona’s fast-changing electorate, which is becoming younger and more diverse. The median age of white Arizonans is 43 while the median age of Latino Arizonans is 26.

Though Latinos are an increasingly influential electoral force, the long anticipated political sea change has yet to arrive. Republicans hold every statewide office in Arizona and Trump carried the state in 2016, albeit by a much smaller margin than the most recent Republican nominees.

But Garcia says the rejection of the two most anti-immigrant candidates by Arizona Republican primary voters, among the most conservative in the nation, was a sign of shifting priorities.

“Business development and economic growth are the top issues now, not immigration,” he said, noting that a national backlash to a so-called “show me your papers” state law in 2010 had shown the economic and political consequences of anti-immigrant policies.

“We are ahead of the rest of the country,” he said. “We’ve already gone through the growing pains that the rest of the nation is experiencing right now.”

Viridiana Hernandez, 27, was only one when she came to the US from Mexico with her family in 1992, the year Arpaio was first elected. She was undocumented and grew up in fear of the day he and his “posse” would come for her family.

That day came in 2014, she said, when deputies raided the construction company where her father worked. He was offsite but he lost his job nonetheless and her family tumbled into economic uncertainty.

Hernandez is now the executive director of a Phoenix-based activist group, Poder in Action.

“There is a group of immigrant children who grew up in an era of hate,” she said. “Now we can vote.”